When Physics meet AI

Docking scores offer a quick first estimate, but often miss the underlying thermodynamics that drive real binding. Chemists have been chasing the dream of predicting binding affinity with accuracy for years, yet the gap between computer scores and lab results keeps showing up like that one stubborn error bar that won’t go away.

The problem? Traditional docking is like judging a relationship by the first handshake. It captures the pose, but not the full thermodynamics that determine real binding affinity. Real binding depends on many hidden players: water molecules, entropy, conformational changes, and sometimes even long-range electrostatics. All that complexity makes accurate prediction tough when using only simplified scoring functions.

That’s where physics and AI come together, one grounded in first principles, the other driven by pattern and inference. Physics brings the rules, thermodynamics, molecular motion, water effects. while AI brings intuition, pattern recognition, and a bit of chaos magic. Together, they’re turning guesswork into something close to real chemistry.

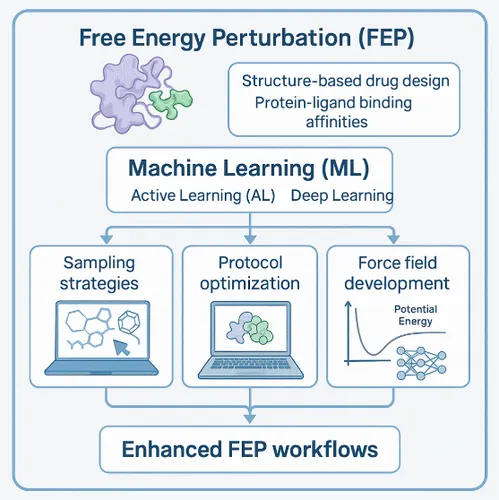

Techniques like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) and Absolute Binding Free Energy (AB-FEP) have long been the “serious calculators” of the bunch, but they were slow and complex. Now, with machine learning–boosted scoring and generative models stepping in, we’re speeding up the process without losing the science.

Machine learning can help predict which molecular poses are worth simulating, approximate energy landscapes faster, and even learn corrections from past free energy errors. Instead of running millions of calculations, AI can help the system “guess smarter."

And as generative models start suggesting molecules that already “fit” a binding pocket, these free energy methods become the filter that decides which ones truly make sense in the physical world. Together, they’re building a feedback loop AI creates, physics validates, and both learn. Now that we know the story; now it’s time to open the lab notebook and see what’s really going on inside these models.

Why Quick Scores Are Fails

In the early stages of drug discovery, we rely heavily on molecular docking. Think of docking as a nightclub bouncer: it quickly screens a massive line of potential compounds (virtual screening) and gives a lightning-fast "yes/no" based on whether the molecule physically fits the binding pocket. It's superb for speed and initial structural insights into the mode of interaction between the ligand and the receptor.

The catch is that the bouncer only looks at the size and shape, not the chemistry. Docking relies on highly simplified, empirical scoring functions designed for throughput, not thermodynamic rigor. These functions intentionally adopt a series of simplifications to reduce complexity, which means they cannot reliably account for the subtle, yet critical, energy changes that occur when a molecule binds, such as changes in solvation (how water molecules rearrange), or entropic effects (how the molecules' flexibility changes). The resulting predicted score is therefore a highly unreliable stand in for the molecule's true value that is the quantitative binding free energy, or ΔG . This fundamental inability to accurately predict the binding strength means drug pipelines are often littered with "false positives" molecules that look good on paper but fail in the lab. Addressing this scoring flaw is currently the most critical priority for industrial drug design, as it limits the ultimate success of virtual screening.

The Mirror Twin Test

The moment you challenge docking with a subtle problem, its facade crumbles. Take enantiomers: mirror-image molecules that are chemically identical but might fit a protein's chiral environment in wildly different ways. Predicting which twin binds better requires capturing every nuance of molecular movement, solvent interaction, and subtle electrical forces—the very things simplified scoring skips over. When docking software (like Glide, considering its extra precision (XP), standard precision (SP), and high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) modes, as well as AutoDock Vina) was put through the "Mirror Twin Test" against 141 pairs of enantiomers with biological activities reported across seven targets, it repeatedly failed. (Rawal & Braga, 2024)

The conclusion? If the software correctly identified the stronger binder, it was purely due to chance. This isn't a simple bug; it's confirmation that the underlying mathematical model cannot capture true thermodynamic reality. When you need precision, you must turn to a model built on physics.

Free Energy's High Cost of Precision

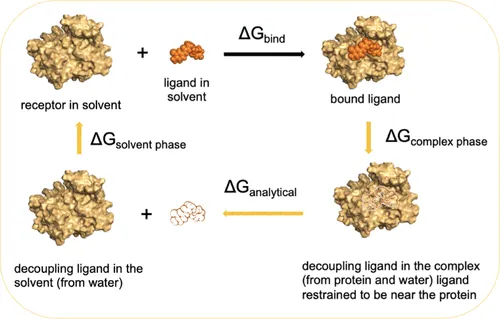

The industry's answer to the prediction crisis is Free Energy Perturbation (FEP). FEP is the forensic accountant of molecular biology, recognized as the gold standard for high-accuracy binding affinity prediction, especially when refining a promising drug candidate (hit-to-lead and lead optimization phases). FEP derives the true ΔG from the laws of statistical mechanics by simulating an "alchemical transformation", a theoretical pathway where one ligand is smoothly mutated into another (Relative FEP) or slowly vanishes from the protein pocket (Absolute FEP, or AFEP). This process is theoretically sound and precise.

The Triple Barrier to Entry: Why FEP Stayed Exclusive

In theory, FEP sounds perfect. In practice, it was the molecular equivalent of a VIP computing club. The FEP formula can be applied without calculating intermediate states (the "end-state-only" approach) only if there is a very high degree of phase-space overlap between the initial (λ=0) and final (λ=1) states. Since this condition is rarely met in complex molecular binding, FEP must painstakingly sample dozens of intermediate states (λ windows) to ensure the full energetic path is correctly mapped. (Braga & Rawal, 2025). This intensive requirement created a "Triple Barrier":

- The Time Sink: Sampling intermediate states demands vast computational power. Even small changes in a molecule require substantial resources, historically limiting FEP to small, exclusive groups of highly congeneric molecules that are chemically very similar.

- The Expert Tax: FEP calculations are highly advanced and require deep, specialized computational expertise for setup, execution, and thorough analysis. You couldn't just hand it to an intern; this requirement acted as a significant barrier to widespread adoption.

- The New Discovery Bottleneck (AFEP): Absolute FEP (AFEP) has the theoretical power to find entirely new, de novo hits because it doesn't require a structural reference molecule. However, its inherently slow throughput historically made it impractical for real-world screening campaigns.

The core issue was simple: FEP’s power was crippled by inefficient sampling, the computer was effectively wandering aimlessly through the molecular landscape.

The mission for AI became clear: Stop the wandering. Provide the GPS. Democratize the gold standard, making it fast and accessible for everyone in drug design.

AI-Driven Sampling Acceleration

Machine learning now provides the algorithmic intelligence to tackle FEP's high computational cost head-on, deploying "smart sampling" to accelerate the exploration of the Free Energy Surface (FES) and the underlying molecular kinetics.

ML for Optimal Path Finding

Traditional molecular dynamics (MD) simulations take too long waiting for a molecule to spontaneously find the complex, low-energy path to its binding site. AI fixes this by defining superior Collective Variables (CVs). These are custom, machine learned coordinates that simplify the high dimensional binding event into a single, optimized path, forcing the simulation to find the "express lane." The COMet-Path hybrid method exemplifies this, combining an enhanced sampling technique (funnel metadynamics) with a machine-learned optimal association CV.

The initial step requires optimizing the coefficients of this pathlike variable, which must be performed on at least one converged free energy landscape, typically obtained with another set of variables. Once optimized, this approach ensures the free energy profile converges significantly faster, particularly for complex ligands in exposed and large binding cavities. This powerful combination delivers a potent blend of accuracy and speed for calculating Absolute Binding Free Energies (ABFE), successfully overcoming the major speed limitation of traditional AFEP methods with minimal additional computational overhead. COMet-Path can provide a satisfactorily accurate estimation of the ABFE for noncongeneric ligands, increasing the success rate compared to using funnel metadynamics alone. (Crivelli-Decker et al., 2024)

Learning the Point of No Return: Transition State Mapping

For methods that trace the physical path of binding, such as Transition Path Sampling (TPS) and Steered Molecular Dynamics (MD), knowing the precise "Point of No Return" the transition state, or committor function is crucial for efficiency. ML algorithms are trained to learn this function directly. The Automated Iterative Molecular Dynamics (AIMMD) method, for instance, iteratively combines TPS with a neural network that estimates the committor function. This intelligence then guides intelligent "shooting" from the transition state to accelerate the exploration of the binding mechanism. Variational approaches are also proposed that minimize the total squared displacement over equilibrium trajectories, bypassing the need to estimate committor values explicitly. A major bonus here is that scientists gain not just the final ΔG number, but rich details on the physical mechanism itself, including binding intermediates, transient pockets, and molecular mechanisms, critical insights that the non-physical, alchemical paths of standard FEP mask entirely.

The AI Art Generator for Molecules: Phase Space Exploration

Generative models, such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Diffusion models, are deployed to enhance molecular structure sampling and implicit density estimation. These deep-learning methods represent a considerable effort focused on enhanced samplings for extracting the free energy surface and kinetics. A VAE-based network can learn simplified, low-dimensional maps (embeddings) of time lagged protein conformations, helping to reveal the slow dynamics of stochastic protein motions crucial for understanding induced fit binding and accurate affinity prediction. Specifically, Wasserstein GANs minimize the difference between the true distribution of molecular structures and the synthetic ones generated. This process, known as implicit density estimation, ensures that the generated samples are highly representative of valid molecular structures and helps avoid issues common in other generative models, such as the posterior collapse problem often seen in VAEs. (Donald & Willem Jespers, 2025)

This capability guarantees efficiency by ensuring computational cycles aren't wasted exploring invalid or non-representative conformations, thereby accelerating the exploration of phase space. Furthermore, the capability to perform efficient conditional generation of molecules, estimating the distribution of a structure given certain desired chemical properties is significantly enhanced through these generative models.

Classical molecular dynamics simulations rely on simplified energy rules (force fields). While fast, these rules are often parameterized based on limited training data and sometimes fail to capture the subtle, critical electronic, polarization, and non-covalent forces crucial for high-precision binding affinity. This is where AI delivers a crucial upgrade in physical fidelity.

Neural Network Potentials

Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) are sophisticated ML models trained on the "master blueprint" of high-level Quantum Mechanical (QM) calculations. They are trained on extensive datasets derived from these QM calculations and learn to represent the complex potential energy surface, achieving near-QM accuracy but running at a fraction of the cost compared to performing full QM dynamics. Integrating these NNPs into FEP directly elevates the quality of the underlying physics, leading to higher fidelity ΔG predictions. These enhancements mark clear progress toward more practical ML-augmented force fields for FEP workflows.

Trajectory Tipping: Solving the Speed vs. Accuracy Trade-off

Running an entire simulation entirely with a highly accurate NNP is still significantly more computationally expensive compared to using a cheap, traditional classical force field. This threatens to reintroduce the old dilemma: accuracy versus throughput.

The brilliant solution is the reweighting strategy, a clever operational hack developed by researchers like Tkaczyk et al. Trajectories are first run cheaply using the simple molecular mechanics (MM) force field. Then, the expensive, accurate NNP (such as ANI-2x) is used to reweight those results, applying a high-precision correction after the fact. This strategy retains the accuracy benefits associated with the neural network potential without committing to the full computational grind for the entire simulation. a powerful and practical compromise that makes high-accuracy, ML-augmented force fields viable for high-throughput FEP workflows. (Zeng et al., 2022)

The Hybrid AI-FEP Pipeline

The combination of physics-based rigor and AI-driven efficiency has operationalized FEP, transforming it from a bespoke lab curiosity into a scalable, industrial-grade predictive platform that actively guides lead optimization in pharmaceutical research.

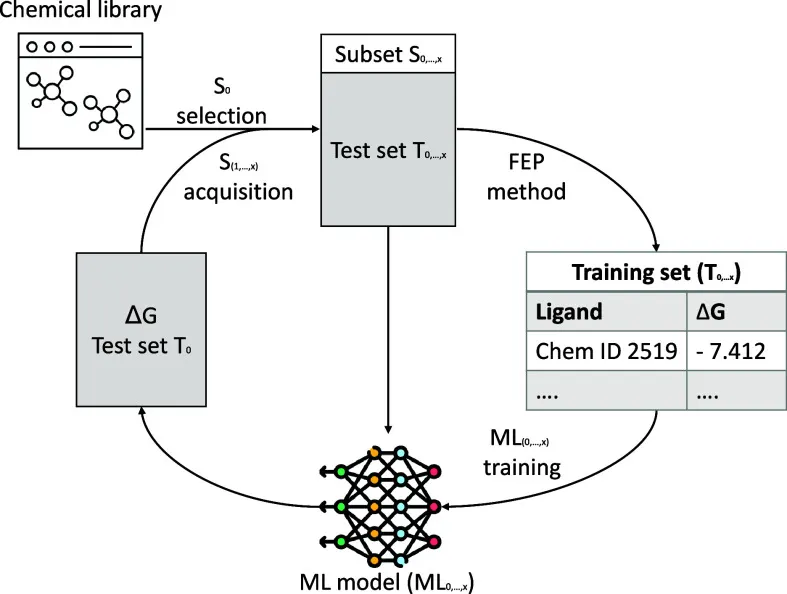

Active Learning for Intelligent Screening

FEP, even accelerated, is pricier than docking. Active Learning (AL) algorithms act as the shrewd stock picker, guiding molecule selection to dramatically reduce the total number of necessary FEP calculations during virtual screening. The process is self-correcting, AL algorithms are trained and informed using small, high-quality virtual activity data sets generated by FEP itself. This ability to generate highly valuable virtual activity data from FEP to train AL algorithms is a crucial factor in overcoming the typical data paucity challenge faced by ML in drug discovery. This establishes a virtuous cycle where FEP provides the ultimate ground truth, which in turn trains the AL to prioritize only the most promising candidates for the next expensive FEP calculation, effectively replacing exhaustive searching with intelligent, iterative optimization.

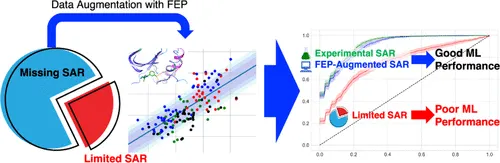

Physics Augments AI. Machine Learning models often suffer from poor performance due to Limited SAR data. By harnessing Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) to create highly reliable, synthetic data points, we overcome this bottleneck. This 'Data Augmentation' transforms a failing model (red curve) into a highly accurate predictor (blue curve), proving that physics is the key to unlocking AI's full potential in drug design

Eliminating the Expert Barrier

Historically, preparing the initial protein-ligand complex structure, the "assembly required" phase was manual, error prone, and demanded deep expertise. This complexity was a major roadblock to FEP adoption. Deep Learning (DL) methods have now completely automated this crucial step. DL based co-folding tools, such as AlphaFold variants, NeuralPLexer, and DragonFold, automatically generate accurate complex structures, which are essential starting points for FEP. This is revolutionary because it bypasses the need for traditional docking or manual complex preparation steps, which drastically lowers the operational complexity and the reliance on specialized experts. This key automation step is crucial, making FEP a robust, accessible tool for high throughput industrial pipelines.

The Report Card: Validating Predictive Power

This hybrid AI-FEP system has moved past academic papers and into the boardroom, proven by hard, quantitative metrics that dictate drug development decisions. Industrial case studies, like those from Bayer Pharma AG,(Donald & Willem Jespers, 2025) confirm that modern free energy calculations have achieved the necessary speed and usability to effectively drive real drug discovery projects, running hundreds of compounds across more than ten different targets (including both retrospective and prospective cases).

Quantitatively, the system delivers a retrospective analysis of 147 calculations showed a gold-standard Mean Unsigned Error (MUE) 0.94 kcal/mol and a high correlation R-value of 0.77. This is a critical milestone, as an MUE below 1.0 kcal/mol is the consensus threshold for a genuinely useful, predictive tool in drug discovery. Furthermore, when FEP was applied prospectively to optimize a lead compound series, it successfully guided optimization efforts that led to a tenfold improvement in activity for lead molecules like imidazotriazine I, without increasing atom count or overall size. These strong quantitative metrics confirm FEP’s graduation to a trusted, reliable decision-making technology for pharmaceutical optimization.(van Pinxteren & Jespers, 2025)

| Metrics | Molecular Docking (VS) | Traditional FEP/MD | AI-Augmented FEP Hybrid |

| Primary Output | Docking Score (Simplified ΔG) | Relative/Absolute Binding Free Energy ΔG | Highly Accurate ΔG (Accelerated) |

| Physical Rigor | Low (Empirical/Knowledge-Based) | High (Statistical Mechanics) | Highest (ML-NNP Enhanced) |

| Accuracy (MUE) | Poor (Prediction due to chance) | High (approx 1-2 kcal/mol) | Predictive (approx 0.94 kcal/mol) |

| Computational Cost | Very Low (High Throughput) | Extremely High (Limited Throughput) | Medium-High (Accelerated via ML/AL) |

| Key AI/ML Role | Minimal | Enhanced Sampling (CVs, Committor) | Force Fields (NNP), Protocol Optimization (AL) |

| Typical Use Case | Hit Identification (Large Screens) | Lead Optimization (Small, Congeneric Sets) | Hit-to-Lead and Lead Optimization (Broad Scope) |

Table. 1 Comparative Metrics: Docking vs. Traditional FEP vs. Hybrid AI-FEP

The successful strategy emphasizes a hybrid approach that integrates human expertise with sophisticated ML tools, accelerating and democratizing FEP-based drug discovery.8 AI serves not to replace the fundamental chemical and physical models, but to optimize and enable them.

| FEP Challenge Addressed | AI/ML Technique Deployed | Mechanism of Enhancement |

| Slow Convergence/Sampling | Machine-Learned Collective Variables (COMet-Path) | Defines optimal, low-dimensional reaction coordinate to speed up free energy surface exploration. |

| Transition State Identification | Committor Function NN/TPS (AIMMD) | Learns the probability of reaching the bound state, promoting smarter sampling from transition regions. |

| Classical Force Field Inaccuracy | Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Trained on QM data to provide higher physical fidelity for energy calculations. |

| NNP High Computational Cost | Reweighting Strategy (ANI-2x) | Applies the accurate NNP corrections to trajectories generated by cheaper classical force fields. |

| Setup Complexity (Initial Pose) | DL Co-folding (AlphaFold variants) | Automates the generation of accurate protein-ligand complex starting structures. |

| Operational Cost/Efficiency | Active Learning (AL) | Guides molecule selection, minimizing the total number of expensive FEP calculations needed. |

Table 2: AI’s Role in Enhancing FEP Workflows

The Next Horizon: Quantum Computing Meets Free Energy

Looking ahead, the ultimate evolution involves integrating quantum computing into this AI-physics framework. Quantum computers hold the potential to tackle the deepest, most intractable problems in quantum chemistry those related to complex electronic interactions and large-scale reaction dynamics that even the most powerful classical supercomputers cannot solve.

Current research is focused on developing qubit-efficient variational quantum algorithms (VQAs) that are resource aware on current quantum hardware. This involves minimizing qubit requirements while maintaining quantum advantages, particularly when solving high-dimensional, combinatorial problems like optimizing coordination in multi-agent systems, a task analogous to optimizing a molecular system.

The future remains strictly hybrid: smartly delegating tasks between classical computation and quantum accelerators to solve the immense, high-dimensional, combinatorial optimization problems inherent in molecular systems. This strategic delegation is crucial because it leverages the advantage of quantum acceleration without overburdening the limited qubit capacity of current devices. Mid-term goals include optimizing quantum circuits specifically for agent interactions and designing more efficient integration strategies that balance quantum and classical computation to expand scalability.

Ultimately, the long-term vision involves using fully fault-tolerant quantum computers (FTQCs) to enable entirely quantum driven agent interactions, decision making, and optimization, finally surpassing all known classical computational limits in molecular simulation and enabling breakthroughs in drug design that are currently impossible.

Conclusion

The convergence of statistical physics (FEP) and Artificial Intelligence is nothing short of a paradigm shift, a true computational revolution. The quick and dirty scores of simplified docking have been definitively eclipsed by a highly predictive platform that operates with near-quantum accuracy and industrial scale throughput.

By providing the molecular GPS for sampling, automating the painful setup phase, simplifying the system through coarse graining, and elevating force fields to quantum fidelity, AI has solved FEP’s three major historical roadblocks. The result is a validated predictive engine with an error rate below the crucial 1.0 kcal/mol threshold. This hybrid approach has not just accelerated the drug discovery timeline; it has profoundly raised the bar for computational rigor in the pharmaceutical industry, ushering in an era where speed and precision no longer have to be mutually exclusive.

The future of drug discovery is not just faster or more accurate, it is fundamentally more intelligent, ensuring that speed and precision are, at long last, inseparable allies in the quest for human health.

References

Cournia, Z., Allen, B., & Sherman, W. (2017). Relative Binding Free Energy Calculations in Drug Discovery: Recent Advances and Practical Considerations. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 57(12), 2911–2937. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00564

Hong, S. H., Ryu, S., Lim, J., & Kim, W. Y. (2019). Molecular Generative Model Based on an Adversarially Regularized Autoencoder. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 60(1), 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00694

Burger, P. B., Hu, X., Balabin, I., Muller, M., Stanley, M., Joubert, F., & Kaiser, T. M. (2024). FEP Augmentation as a Means to Solve Data Paucity Problems for Machine Learning in Chemical Biology. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 64(9), 3812–3825. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.4c00071

York, D. M. (2023). Modern Alchemical Free Energy Methods for Drug Discovery Explained. ACS Physical Chemistry Au, 3(6), 478–491. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsphyschemau.3c00033

van Pinxteren, D. J. M., & Jespers, W. (2025). Integrating Machine Learning into Free Energy Perturbation Workflows. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 65(19), 9856–9864. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.5c01449

Crivelli-Decker, J. E., Beckwith, Z., Tom, G., Le, L., Khuttan, S., Salomon-Ferrer, R., Beall, J., Gómez-Bombarelli, R., & Bortolato, A. (2024). Machine Learning Guided AQFEP: A Fast and Efficient Absolute Free Energy Perturbation Solution for Virtual Screening. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.4c00399

Braga, D. M., & Rawal, B. (2025). Harnessing AI and Quantum Computing for Revolutionizing Drug Discovery and Approval Processes: Case Example for Collagen Toxicity. JMIR Bioinformatics and Biotechnology, 6, e69800–e69800. https://doi.org/10.2196/69800

Ramírez, D., & Caballero, J. (2016). Is It Reliable to Use Common Molecular Docking Methods for Comparing the Binding Affinities of Enantiomer Pairs for Their Protein Target? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 17(4), 525–525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17040525

Matsumura, N., Yoshimoto, Y., Yamazaki, T., Amano, T., Noda, T., Ebata, N., Kasano, T., & Sakai, Y. (2025). Generator of Neural Network Potential for Molecular Dynamics: Constructing Robust and Accurate Potentials with Active Learning for Nanosecond-Scale Simulations. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 21(8), 3832–3846. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.4c01613