Structural Plasticity in the Mutome: Mechanisms of Binding Pocket Alteration and Therapeutic Intervention

1. From Handshakes to Dynamic Landscapes

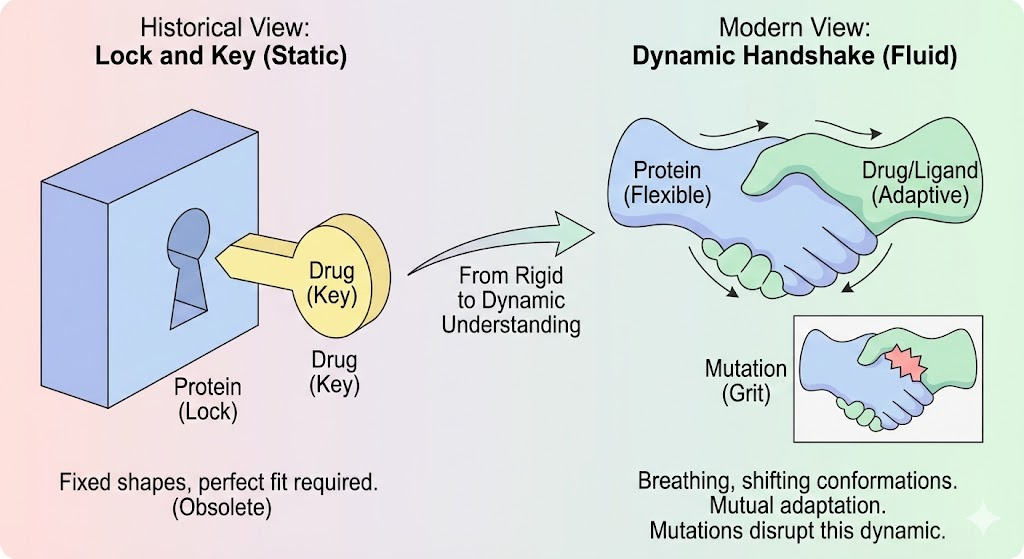

Imagine a handshake. It seems like a simple gesture, two hands clasping. But consider the nuance. If your hand is rigid like stone, the handshake fails. If it is too limp, the connection is weak. A perfect handshake requires the hand to conform, to adjust its pressure and shape in response to the other person. It is a dynamic, mutual adaptation. For over a century, biology textbooks taught us that proteins and drugs interact like a "Lock and Key". In this rigid, mechanical analogy, the protein (the lock) sits frozen in a single shape, waiting for a perfectly carved ligand (the key) to slide in. While this model, championed by Emil Fischer in 1894, gave us the basic concept of specificity, it is, in the modern view, functionally dead. Proteins are not locks. They are breathing, vibrating, shifting molecular machines. They are closer to the "handshake" or a "glove fitting a hand". They exist in a constantly shifting landscape of shapes an ensemble of conformations.

In the high-stakes world of oncology, this dynamic nature is where the battle is fought. Cancer is often described as a disease of the genome, but functionally, it is a disease of the proteome's structure. A single mutation in a DNA sequence translates to a swapped amino acid in a protein. This tiny change can act like a piece of grit in a gearbox or a wedge in a door. It can lock a protein in an "always-on" handshake, signaling cells to divide uncontrollably. It can reshape a binding pocket just enough that a life-saving drug can no longer fit, or it can create a brand-new, secret cavity a "cryptic pocket" that we never knew existed.(Structural Biochemistry/Protein Function/Lock and Key - Wikibooks, Open Books for an Open World, 2022)

This Blog explores the structural biology of the "Mutome" the universe of mutant proteins driving cancer. We will journey from the atomic physics of binding pockets to the clinical realities of drug resistance. We will dismantle the mechanisms of notorious killers like EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF, and see how computational wizardry is helping us find pockets that don't exist until we look for them. This is the story of how shape dictates destiny in cancer biology.

2. The Biophysics of Binding: Beyond the Lock and Key

To understand how cancer mutations wreak havoc, we must first establish the physical rules of how drugs bind to proteins. The interaction is governed by thermodynamics, specifically the Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔG), which dictates the affinity of a drug for its target.(Tripathi & Bankaitis, 2018)

2.1 The Thermodynamics of Specificity The binding event is a delicate balance between enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS).

Enthalpy (ΔH): This represents the heat energy released or absorbed. It is driven by specific interactions: hydrogen bonds (like Velcro hooks), salt bridges (magnetic attraction between charges), and van der Waals forces (shape complementarity). A mutation that removes a hydrogen bond donor, for example, changing a Threonine to an Alanine, directly penalizes enthalpy.

Entropy (ΔS): This reflects the disorder of the system. When a drug binds, it loses its freedom to tumble in solution (unfavorable entropy). However, binding often displaces highly ordered "unhappy" water molecules trapped in the pocket, releasing them into the bulk solvent (favorable entropy). This "hydrophobic effect" is a primary driver of drug binding.

2.2 The Solvation Landscape

Water is not just a background solvent; it is a structural participant. In many binding pockets, water molecules bridge the interaction between protein and ligand. A mutation that changes the polarity of a pocket say, replacing a hydrophobic Leucine with a polar Arginine completely reorganizes these water networks. The drug must now pay a higher energetic penalty to strip these water molecules away (desolvation penalty) before it can bind. This subtle shifting of "water architecture" is often how resistance mutations work without causing obvious steric clashes.(RLO: Lock and Key Hypothesis, 2025)

2.3 Models of Binding: Induced Fit vs. Conformational Selection

The "Lock and Key" model fails because it assumes rigidity. Current biophysics relies on two more sophisticated models :

- Induced Fit: The protein is flexible but exists in a ground state. As the ligand approaches, its electrostatic and chemical field induces a conformational change in the protein, molding the pocket around the ligand. This is the "hand in glove" model.

- Conformational Selection: The protein naturally fluctuates between many shapes (an ensemble) even without the ligand. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes one of these pre-existing, high-energy conformations. This model is crucial for understanding allosteric inhibitors, which bind to shapes that might only exist for a microsecond

Cancer mutations perturb these dynamics. A mutation might destabilize the "inactive" shape of a kinase, shifting the entire population toward the "active" shape. If a drug prefers the inactive shape (as many do), it suddenly finds no target to bind to, even if the binding pocket itself looks unchanged in a static crystal structure.

3. Mechanisms of Mutation-Induced Pocket Alteration

Somatic missense mutations single amino acid substitutions are the architects of structural resistance. They alter binding pockets through distinct physical mechanisms.

3.1 Steric Hindrance: The "Gatekeeper" Phenomenon

The most direct mechanism is the introduction of bulk. Inhibitor binding pockets often contain a deep hydrophobic cleft. A residue located at the entrance or "gate" of this cleft controls access.

- Mechanism: If a small residue (like Threonine) is mutated to a bulky one (like Methionine or Isoleucine), the side chain physically protrudes into the space occupied by the drug. This is the "Gatekeeper" mutation seen across the kinome (e.g., T790M in EGFR, T315I in ABL).

- Nuance: It is rarely just steric. As we will see with EGFR, bulky residues also enhance van der Waals interactions with the natural substrate (ATP), effectively increasing the "fuel" affinity and allowing the enzyme to outcompete the inhibitor.

3.2 Electrostatic Remodeling

Replacing a neutral residue with a charged one (or vice versa) alters the electrostatic potential surface of the pocket.

In the ABL kinase, resistance mutations often occur not in the deep pocket but on the P-loop (phosphate-binding loop) which clamps down on the drug. A mutation here might alter the charge distribution, disrupting the electrostatic steering that guides the drug into the pocket.

- pH Dependence: Some mutations alter the pKa of surrounding residues, making binding sensitive to the cellular pH environment, a factor often overlooked in standard assays.

4. Case Study: The EGFR Gatekeeper Saga

The Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) is the "poster child" for structural oncology. Its journey from a targetable driver to a resistant mutant and back again illustrates the arms race between drug design and protein evolution.

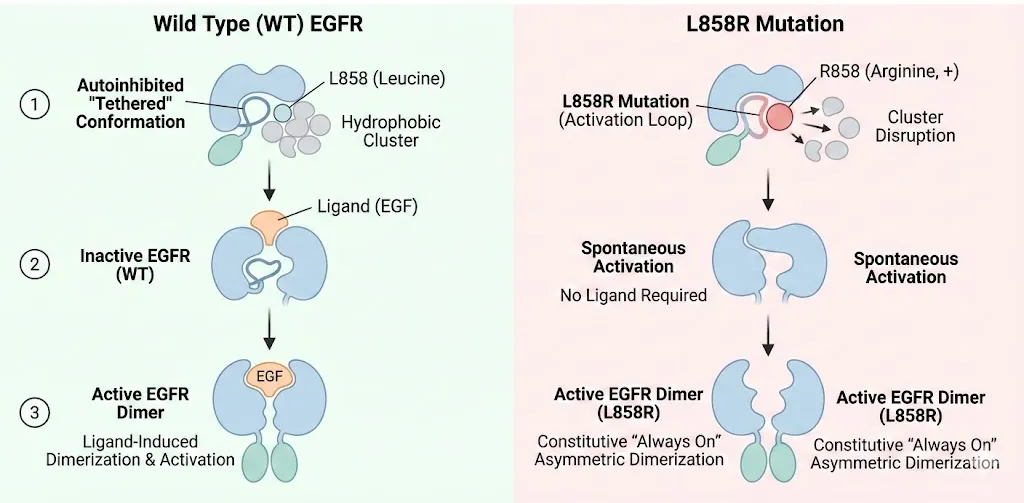

4.1 The Structural Basis of Activation (L858R and Del19) In healthy cells, EGFR exists in an equilibrium favoring an autoinhibited tethered conformation. Ligand binding (like EGF) induces dimerization and activation. • L858R: This mutation, located in the activation loop, substitutes a hydrophobic Leucine with a large, positively charged Arginine. In the Wild Type (WT) protein, Leucine 858 packs into a hydrophobic cluster that stabilizes the inactive helical conformation. The Arginine disrupts this cluster, preventing the inactive state from forming. Consequently, the kinase snaps into the active conformation an asymmetric dimer even without a ligand. This "always on" state drives the cancer.

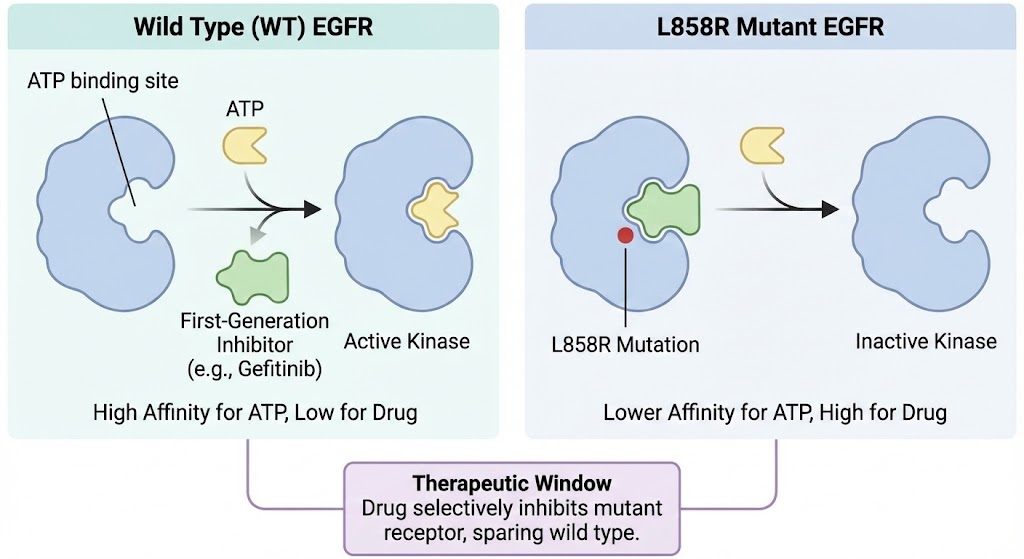

4.2 The First Generation: Competitive Inhibition First generation drugs like Gefitinib and Erlotinib are reversible, ATP competitive inhibitors. They work because the L858R mutation, while activating the kinase, also lowers its affinity for ATP compared to the drug (specifically, it has a lower Km for the drug relative to ATP than WT). This "therapeutic window" allows the drug to shut down the mutant receptor while sparing the wild type receptor in healthy tissues.(Zhu et al., 2018)

4.3 The T790M Resistance Mechanism: A Biophysical Debate

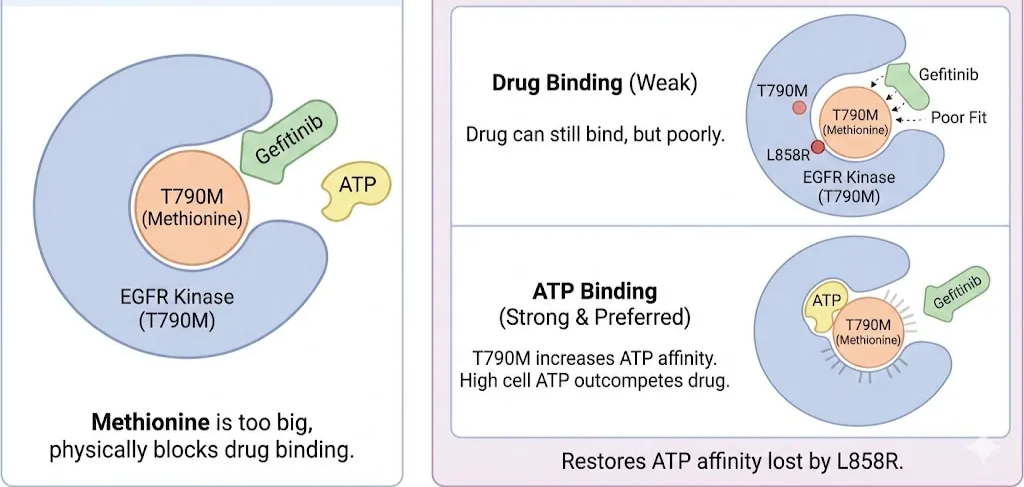

Inevitably, tumors develop resistance. In ~50% of cases, this is due to the T790M mutation. Threonine 790 is the "gatekeeper" residue located deep in the ATP-binding cleft.

• The Steric Hypothesis: Initially, it was believed that the Methionine side chain was simply too big, physically blocking Gefitinib binding.

• The Affinity Hypothesis (The Real Culprit): Detailed kinetic and structural studies revealed a more sophisticated mechanism. Methionine does not completely block Gefitinib binding; the drug can still fit (albeit poorly). However, the T790M mutation drastically increases the receptor's affinity for ATP. The Methionine side chain creates a perfect hydrophobic environment for the adenine ring of ATP, locking it in tighter. In the cell, where ATP concentration is high (millimolar range), the drug can no longer compete. T790M restores the ATP affinity that the original L858R mutation had lost.(Spellmon et al., 2017)

4.4 Third-Generation Covalent Solutions

To defeat T790M, chemists changed the rules. Instead of competing reversibly, they designed Osimertinib (and others like Rociletinib). These drugs carry a "warhead" an acrylamide group. They bind to the pocket and then undergo a Michael addition reaction with a specific residue: Cysteine 797 (C797).

• The Structural Trick: Once the covalent bond forms, the affinity is effectively infinite. The drug cannot wash off. Even if T790M makes the pocket love ATP, the covalent drug permanently occupies the site, shutting down the kinase.(Maloney et al., 2021)

4.5 The C797S Counter-Move and the "Hydrophobic Clamp"

The tumor eventually counters with C797S (Cysteine to Serine).

- Loss of Handle: Serine lacks the thiol group needed for the covalent bond. Osimertinib becomes a reversible inhibitor again, and because of T790M, it loses to ATP.(Yun et al., 2008)

- Structural Remodeling: But it goes deeper. Structural analysis of C797S mutants revealed the importance of a "Hydrophobic Clamp" (residues Leu718 and Val726). The mutation alters the flexibility of this region. New "fourth-generation" allosteric inhibitors (like EAI045) attempt to bypass the ATP site entirely by binding to a separate allosteric pocket created by the displacement of the C-helix, effectively clamping the kinase jaw shut from the outside(Kar et al., 2010)

| Stage | Mutation | Structural Effect | Drug Class | Resistance Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncogenesis | L858R / Del19 | Destabilizes inactive state; promotes active asymmetric dimer. | 1st Gen (Gefitinib) | High affinity for active mutant state. |

| Acquired Resistance | T790M | Increases affinity for ATP; restores Km for ATP to WT levels; steric clash. | 2nd Gen (Afatinib) / 3rd Gen (Osimertinib) | T790M outcompetes reversible drugs; 3rd Gen uses covalent bond to C797. |

| Late Resistance | C797S | Removes nucleophilic thiol (SH to OH); prevents covalent bonding. | 4th Gen (EAI045) | Drug reverts to reversible binding and is outcompeted by ATP. |

| Allosteric Escape | L718Q / G724S | Alters "Hydrophobic Clamp" geometry; steric clash with drug core. | Allosteric Inhibitors | Changes in pocket shape preventing binding. |

Table: Examples of few more mutation and their drug class

5. Computational Frontiers: Hunting the Invisible

How do we find pockets that only exist for a microsecond? We use computational microscopes.

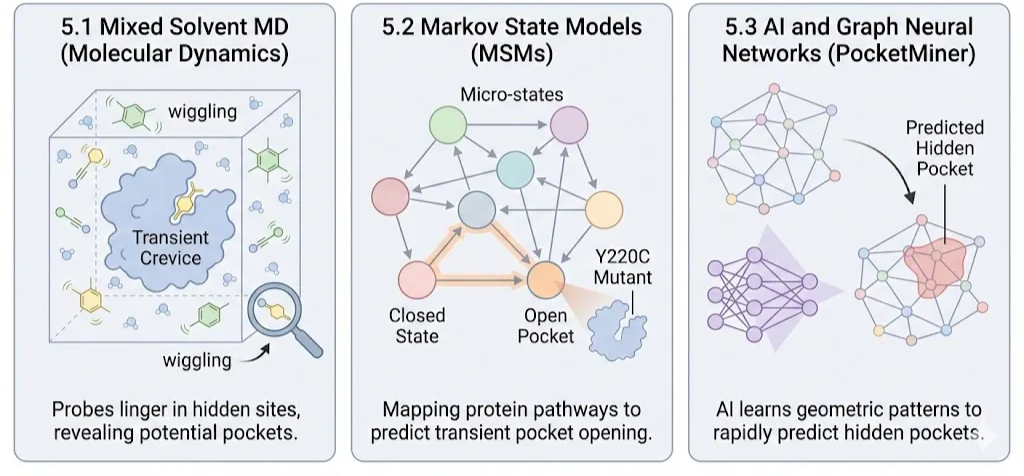

5.1 Molecular Dynamics (MD) and "Mixed Solvents"

Static crystallography is blind to cryptic pockets. MD simulations act as a movie.

Mixed Solvent MD, Researchers flood the virtual simulation box not just with water, but with small organic probes (benzene, acetonitrile). These probes wiggle into transient crevices on the protein surface(Dmitri Beglov et al., 2018). If a probe lingers in a spot (high residence time), it indicates a potential "cryptic" binding site that can be wedged open by a drug.(Li et al., 2014)

5.2 Markov State Models (MSMs)

Proteins transition between thousands of micro-states. MSMs map these states into a network.(Creative Biostructure, 2024)

Mapping the Path: By simulating thousands of short trajectories and stitching them together, MSMs can predict the pathway a protein takes to open a cryptic pocket. This revealed, for instance, that the "undruggable" p53 Y220C mutant possesses a transiently open trench that could be targeted to stabilize the protein.(Oleinikovas et al., 2016)

5.3 AI and Graph Neural Networks (PocketMiner)

MD is computationally expensive (months of supercomputer time). New AI tools like PocketMiner treat the protein structure as a geometric graph.

Pattern Recognition: Trained on thousands of MD trajectories, the AI learns to recognize the subtle geometric "wobble" of residues that precedes the opening of a pocket. It can scan the entire human proteome in days, predicting which "smooth" proteins might actually have hidden pockets waiting to be drugged.(Meller et al., 2023)

6. Conclusion:

The battle against cancer mutations is no longer just about finding a molecule that fits a hole. It is about understanding the fourth dimension of biology: time and motion.

- Enthalpy dictates the strength of the grip.

- Entropy dictates the cost of freezing the motion.

- Water dictates the hidden energy penalties.

- Kinetics dictates how long the drug holds on.

We have moved from the "Lock and Key" to the "Dynamic Ensemble." We are designing drugs that act as molecular glue, allosteric wedges, and covalent traps. We are using supercomputers to watch proteins breathe and AI to predict their next move. The Mutome is complex and adaptive, but by understanding the deep physics of its structural plasticity, we are slowly learning how to lead the dance.

References

References Creative Biostructure. (2024, August 18). Protein-Ligand Interaction. Creative-Biostructure.com; Creative Biostructure. https://www.creative-biostructure.com/proteinligand-interation.htm

Dmitri Beglov, Hall, D. R., Wakefield, A. E., Luo, L., Allen, K. N., Dima Kozakov, Whitty, A., & Vajda, S. (2018). Exploring the structural origins of cryptic sites on proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences, 115(15), E3416–E3425. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711490115

Kar, G., Keskin, O., Gursoy, A., & Nussinov, R. (2010). Allostery and population shift in drug discovery. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 10(6), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.002

Li, M., Petukh, M., Alexov, E., & Panchenko, A. R. (2014). Predicting the Impact of Missense Mutations on Protein–Protein Binding Affinity. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 10(4), 1770–1780. https://doi.org/10.1021/ct401022c

Maloney, R. C., Zhang, M., Jang, H., & Nussinov, R. (2021). The mechanism of activation of monomeric B-Raf V600E. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 19, 3349–3363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csbj.2021.06.007

Meller, A., Ward, M., Borowsky, J., Meghana Kshirsagar, Lotthammer, J. M., Oviedo, F., Ferres, J. L., & Bowman, G. R. (2023). Predicting locations of cryptic pockets from single protein structures using the

PocketMiner graph neural network. Nature Communications, 14(1), 1177–1177. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-36699-3

Oleinikovas, V., Saladino, G., Cossins, B. P., & Gervasio, F. L. (2016). Understanding Cryptic Pocket Formation in Protein Targets by Enhanced Sampling Simulations. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 138(43), 14257–14263. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.6b05425

RLO: Lock and Key Hypothesis. (2025). Nottingham.ac.uk. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/helmopen/rlos/pharmacology/pharmacodynamics/lock_and_key/2.html

Spellmon, N., Li, C., & Yang, Z. (2017). Allosterically targeting EGFR drug-resistance gatekeeper mutations. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 9(7), 1756–1758. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2017.06.43

Structural Biochemistry/Protein function/Lock and Key - Wikibooks, open books for an open world. (2022). Wikibooks.org. https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Structural_Biochemistry/Protein_function/Lock_and_Key

Tripathi, A., & Bankaitis, V. A. (2018). Molecular Docking: From Lock and Key to Combination Lock. Journal of Molecular Medicine and Clinical Applications, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.16966/2575-0305.106

Yun, C.-H., Mengwasser, K. E., Toms, A. V., Woo, M. S., Greulich, H., Wong, K.-K., Meyerson, M., & Eck, M. J. (2008). The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(6), 2070–2075. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0709662105

Zhu, S.-J., Zhao, P., Yang, J., Ma, R., Yan, X.-E., Yang, S.-Y., Yang, J.-W., & Yun, C.-H. (2018). Structural insights into drug development strategy targeting EGFR T790M/C797S. Oncotarget, 9(17), 13652–13665. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.24113