Small Molecule vs Peptide Competition for the Same Pocket

In the high stakes world of modern drug discovery, finding a binding pocket on a disease causing protein is only half the battle. The real challenge and the subject of intense biophysical debate is deciding what kind of "key" should fit that lock.

For most of the 20th century, the pharmaceutical industry placed its bets on Small Molecules: rigid, synthetically crafted chemical structures (typically under 500 Daltons) designed to fit into deep enzymatic pockets with sub angstrom precision. These are the "lock picks" of biology. They are precise, efficient, and easily swallowed in a pill. But biology is rarely static. As we move toward the frontier of "undruggable" targets specifically Protein-Protein Interactions (PPIs) the terrain changes. We are no longer looking at deep, stable caverns, but at vast, flat, and shifting landscapes. Here, a new competitor dominates: Peptides.

This is not merely a difference in size; it is a clash of biophysical philosophies. Small molecules rely on Enthalpy (the energy of static attraction), while peptides are masters of Entropy (the energy of disorder and dynamics).

In this post, we will dissect the competition between these two modalities. We will move beyond the simple "lock and key" analogy to explore the deep physics of shape complementarity, the chaotic war for water displacement, and the kinetic race to the pocket.

To understand why small molecules and peptides behave so differently, you first have to look at the battlefield. The structural "terrain" of a binding site dictates the rules of engagement.

The Small Molecule: The "Lock Pick"

Small molecules are designed for deep concavity. They thrive in active sites the catalytic clefts of enzymes like kinases or proteases. In these deep pockets, a small molecule can be surrounded on almost all sides by protein residues. This high degree of enclosure allows the molecule to maximize Van der Waals interactions (packing forces) despite having a small mass. Because they have a limited surface area (typically burying only 300–500 Å ), small molecules cannot afford "wasted" space. They must achieve what medicinal chemists call Ligand Efficiency (LE). Every atom must contribute to the binding energy. They rely on "hotspots" specific residues (often Tryptophan, Tyrosine, or Arginine) that act as anchors. A small molecule must position a hydrogen bond donor or acceptor with sub-angstrom precision to match these anchors. If the pocket shifts by even 0.5 Å, the "lock pick" may fail to turn.

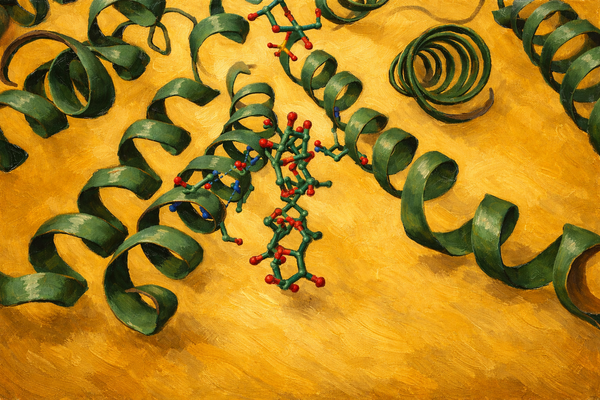

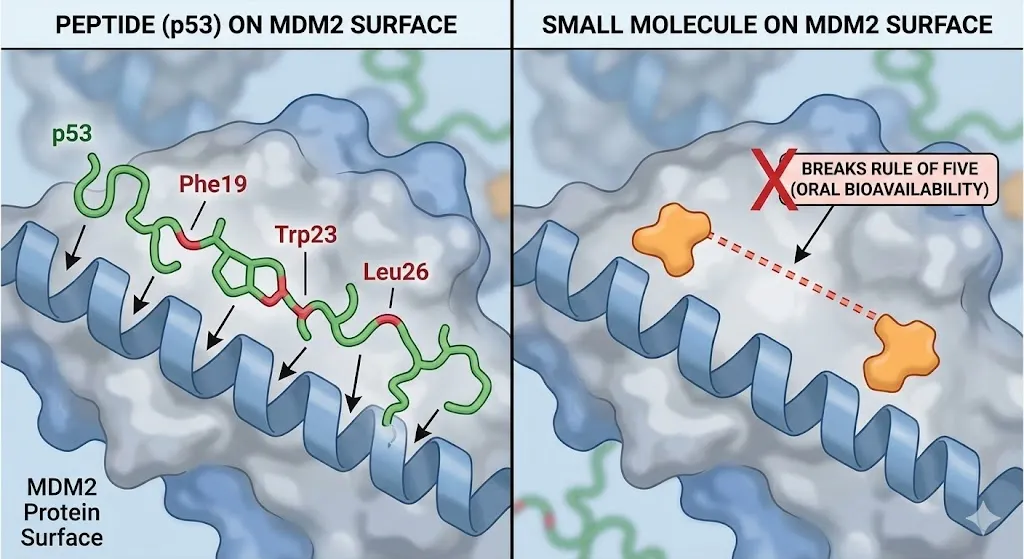

The Peptide: The "Velcro Handshake"

Peptides, by contrast, are evolved to dominate open plains. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) interfaces are typically large (1,000–2,000 Å), flat, and hydrophobic. A small molecule trying to bind here is like a climber trying to scale a glass wall there are no deep crevices to grab.(Vikram Gaikwad et al., 2025) Peptides solve this through Distributed Affinity. Instead of relying on a single deep anchor, they spread their interactions across a massive surface area. They act like "molecular velcro." Even if one section of the interface releases, the rest holds firm. This allows peptides to bridge discontinuous sub-pockets that are far apart. For example, the p53 tumor suppressor peptide interacts with the MDM2 protein by inserting three specific residues (Phe19, Trp23, Leu26) into shallow clefts spread across a long helix. A small molecule has to be artificially stretched or "linked" to cover that same distance, often breaking the rules of oral bioavailability (Rule of Five) in the process. (Atanu Maity et al., 2020).

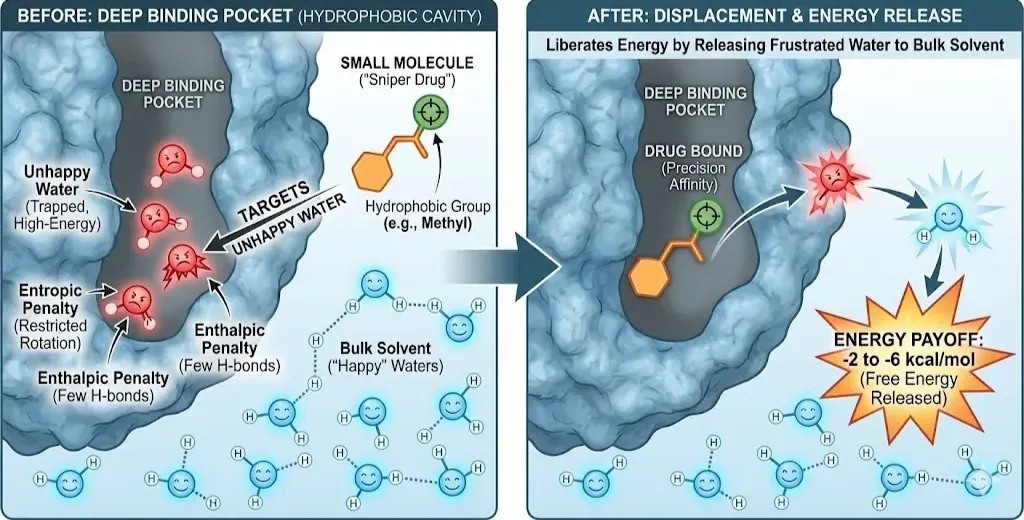

The Water Game: "Unhappy" Water vs. The Hydrophobic Effect

Water is not just a passive background solvent; it is an active, aggressive competitor for the binding site. Before a drug can bind to a protein, it must strip away the water molecules clinging to the protein surface. This "desolvation" cost is the thermodynamic gatekeeper of binding.

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.

Small Molecules: The Sniper Approach

In deep binding pockets, water molecules often get trapped. A water molecule in the bulk solvent is "happy", it can tumble freely and form 3 to 4 hydrogen bonds with its neighbors. But when a water molecule is trapped in a hydrophobic protein cavity, it loses this freedom. It cannot rotate (entropic penalty) and may not find enough partners to hydrogen bond with (enthalpic penalty). These are termed "Unhappy Waters" or high-energy hydration sites.(DeAngelo et al., 2025) Small molecules exploit this misery. A central strategy in modern drug design is to place a hydrophobic group (like a methyl or chloro group) exactly where an "unhappy" water molecule sits. By displacing this frustrated water molecule and releasing it back into the bulk solvent, the drug liberates energy.

- The Energy Payoff: Releasing a single "unhappy" water molecule can yield between -2 to -6 kcal/mol of free energy.

- Precision: Small molecules act like snipers, targeting these specific high-energy waters to generate affinity without needing a massive surface area.(Raddi & Voelz, 2023)

Peptides: The Bulk Approach

Peptides play a different game. Because they cover such a vast surface area, they don't just displace one or two waters; they displace a whole network. This is the Hydrophobic Effect operating on a macro scale.

When a peptide binds to a flat hydrophobic interface, it releases dozens of water molecules from the protein surface. While these surface waters are not as "unhappy" as the deep cavity waters (the energy gain per molecule is lower, perhaps -0.5 to -1.0 kcal/mol), the quantity is what matters. The release of 20 or 30 water molecules generates a massive surge of solvent entropy ( ΔS{solv}. This entropic boost is often the primary engine that drives peptide binding, compensating for the fact that their individual hydrogen bonds might not be as optimized as those of a synthetic small molecule.

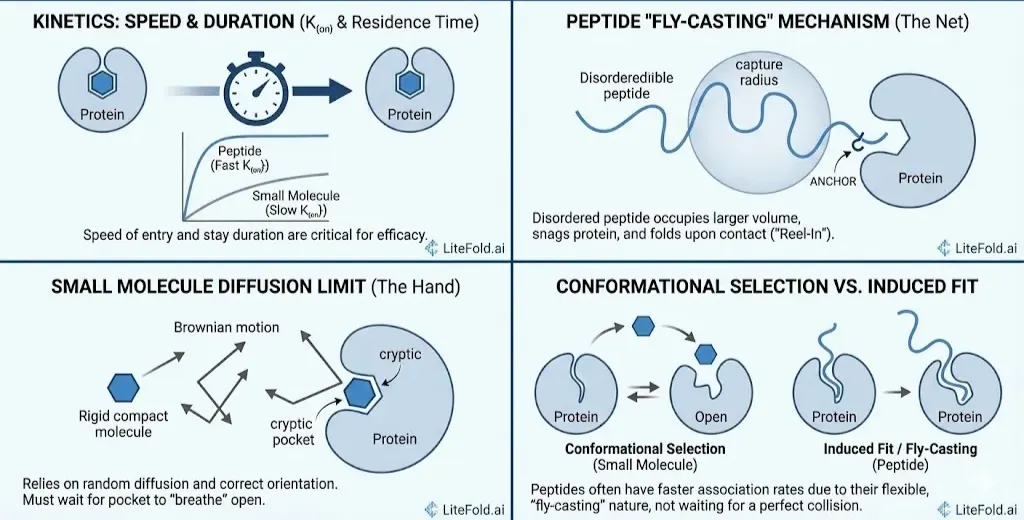

The Kinetic Race: How They Enter the Pocket

Thermodynamics tells us if a binding event will happen; kinetics tells us how fast. Recent research has shown that the speed of entry (K{on}) and the duration of stay (Residence Time) are critical for drug efficacy. Here, the flexible nature of peptides gives them a surprising advantage.

The "Fly-Casting" Mechanism

You might assume that a floppy, disordered peptide would bind slower than a rigid, compact small molecule. The opposite is often true. Peptides, particularly intrinsically disordered ones (IDPs), utilize a mechanism known as Fly-Casting. Imagine trying to catch a ball (the protein) with your hand (the small molecule) versus catching it with a large net (the peptide).

- The Net: In solution, the disordered peptide has a large "capture radius." It occupies a greater volume of space than a compact molecule.

- The Hook: One end of the peptide (the "anchor" residue) makes the initial contact with the protein.

- The Reel-In: Once anchored, the rest of the peptide folds down onto the protein surface in a "dock-and-coalesce" maneuver.

This allows peptides to have association rates (K{on}) that are 1.5 to 2.5 times faster than the diffusion limit of a rigid sphere.They don't have to wait for a perfect collision; they snag the protein and reel themselves in.(“Overcoming the Shortcomings of Peptide-Based Therapeutics,” 2022)

Small Molecules: The Diffusion Limit

Small molecules rely on Brownian diffusion. They zip around the solution and must hit the binding pocketw with the correct orientation. If the pocket is "cryptic" (meaning it is closed most of the time and only flickers open occasionally), the small molecule is at the mercy of the protein's internal dynamics.(Wang et al., 2021) It must wait for the protein to "breathe" open—a mechanism called Conformational Selection. This can severely limit how fast a small molecule can bind, making it difficult to target proteins with short half lives.(Wang et al., 2023)

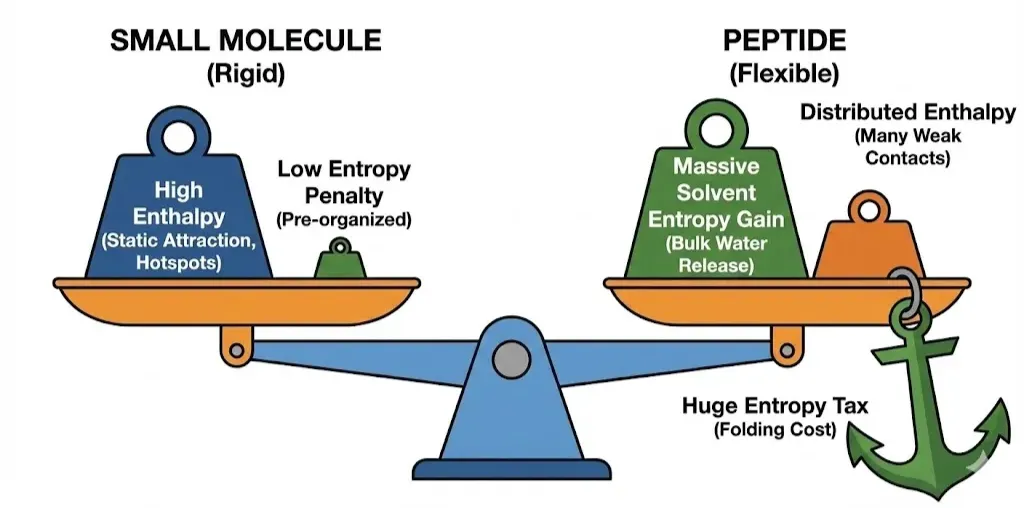

The Thermodynamic Bill: The "Entropy Tax"

Everything in biophysics comes with a price tag. The currency is Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG = ΔH − TΔS). While peptides have advantages in water release and kinetics, they pay a massive tax that small molecules avoid.

The Conformational Entropy Penalty

A small molecule is usually rigid. It looks the same in solution as it does bound to the protein. It is "pre-organized." A peptide, however, is flexible. In solution, it is a chaotic ensemble of thousands of different shapes. To bind, it must freeze into a specific shape (like an alpha-helix). This loss of freedom is the Conformational Entropy Penalty (ΔSconf).

- The Cost: For a standard peptide, freezing its backbone into a helix costs a massive amount of energy (10–20 kcal/mol of unfavorable entropy).

- The Compensation: To overcome this "entropy tax," the peptide must generate enormous binding energy (Enthalpy) and release huge amounts of water (Solvent Entropy).

This is why natural peptides often have only micromolar affinity. They spend most of their binding energy just paying off the debt of folding. Small molecules, having pre-paid this cost during synthesis (by being rigid rings), can achieve nanomolar affinity with far fewer contacts.(Greives & Zhou, 2014)

Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation

This leads to a phenomenon known as Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation. If medicinal chemists try to make a peptide tighter and more rigid (to improve Enthalpy), they often find that the Entropic gain decreases.

However, peptides exhibit a unique property called Entropy-Enthalpy Transduction. Because they are large and coupled to the protein's own movements, a strong interaction at one end of the peptide can loosen the protein structure at the other end, releasing entropy elsewhere. This allows peptides to "cheat" the compensation rule in ways rigid small molecules cannot.

Structural Plasticity: The Resistance Problem

One of the most compelling arguments for peptide-based therapeutics (or "peptidomimetics") is their resilience against drug resistance.

The Brittle Small Molecule

Small molecules are often described as "brittle." Because they rely on precise, lock and key complementarity, a single point mutation in the protein can destroy binding.

- Case Study: Bcl-2 and Venetoclax. Venetoclax is a powerful small molecule drug that binds to the Bcl-2 protein to treat leukemia. However, patients can develop a resistance mutation, G101V. This mutation replaces a tiny Glycine residue with a bulky Valine.

- The Clash: The rigid Venetoclax molecule cannot accommodate this extra bulk. It clashes with the Valine, and binding affinity drops over 100-fold, rendering the drug ineffective.

The Plastic Peptode

The native ligand for Bcl-2 is the BIM BH3 peptide. Remarkably, the BIM peptide binds to the mutant G101V protein almost as tightly as it binds to the wild type. The peptide is plastic. When it encounters the bulky Valine mutation, the peptide backbone slightly shifts or "unwinds" by a fraction of an Angstrom. It routes its side chains around the obstacle. The entropic cost of this small adjustment is negligible compared to the total binding energy. This "structural plasticity" suggests that peptides (or flexible, peptide like molecules) are more robust long-term solutions for targets prone to mutation, such as viral proteins or cancer targets.(Vogt & Cera, 2012)

The Future: Hybrids and Chimeras

The binary distinction between "small molecule" and "peptide" is rapidly fading. The pharmaceutical industry is now chasing Chimeras. A molecules that attempt to capture the best of both worlds.

Stapled Peptides

To solve the "Entropy Tax" problem of peptides, chemists use Stapling. By chemically locking a peptide into an alpha-helix before it enters the body, they pre-pay the entropy cost. Stapled peptides (like ATSP-7041 targeting MDM2) bind tighter than native peptides because they don't lose as much entropy upon binding. They also resist degradation by enzymes and can sometimes penetrate cells.

PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras)

These are large, distinct molecules connected by a flexible linker. They behave like peptides in their kinetics. The flexible linker allows the molecule to search for its target using a mechanism similar to fly-casting, and they induce the formation of a ternary complex (Target-PROTAC-Ligase) that mimics a Protein-Protein Interaction.

| Feature | Small Molecule | Peptide |

| Analogy | The Lock Pick | The Velcro Handshake |

| Primary Target | Deep, rigid pockets (Enzymes) | Flat, broad interfaces (PPIs) |

| Water Strategy | "Sniper": Displace high-energy trapped waters | "Bulk": Massive surface water release |

| Binding Entry | Diffusion & Conformational Selection | Fly-Casting & Induced Fit |

| Thermodynamics | Enthalpy-driven (Pre-organized) | Entropy-driven (Solvent release vs. Folding cost) |

| Resistance | Brittle (Mutation kills binding) | Plastic (Adapts to mutations) |

| Key Weakness | Undruggable flat surfaces | Membrane permeability & Metabolic stability |

Table: Overall comparison between small molecules and peptide

Conclusion

The competition for the pocket is not just about which molecule fits best; it is about which molecule manages the chaos of biology most effectively.

Small molecules remain the champions of the deep pocket being efficient, precise, and lethal to enzymes. But as we tackle the complex web of Protein-Protein Interactions, the peptide’s ability to hug the surface, release bulk water, and adapt to mutations offers a distinct advantage. The future of drug discovery likely lies in the middle ground: rigidifying peptides to lower their entropy tax (stapling) or making small molecules large enough to mimic the "handshake" of a protein (macrocycles). Understanding these biophysical rules from the "unhappy" water molecule to the "fly-casting" entry is the key to unlocking the next generation of therapeutics.

References

Atanu Maity, Choudhury, A. R., Chakrabarti, R., Atanu Maity, Choudhury, A. R., & Chakrabarti, R. (2020). Effect of Stapling on the Thermodynamics of mdm2-p53 Binding. BioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.28.424518

DeAngelo, T. M., Utsarga Adhikary, Korshavn, K. J., Seo, H.-S., Brotzen-Smith, C. R., Camara, C. M., Sirano Dhe-Paganon, Bird, G. H., Wales, T. E., & Walensky, L. D. (2025). Structural insights into chemoresistance mutants of BCL-2 and their targeting by stapled BAD BH3 helices. Nature Communications, 16(1), 8623–8623. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63657-y

Gaikwad, V., Choudhury, A. R., & Chakrabarti, R. (2025). Microscopic Insights into the Solvation of Stapled Peptides–A Case Study of p53-MDM2. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 129(29), 7499–7510. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.5c03100

Greives, N., & Zhou, H.-X. (2014). Both protein dynamics and ligand concentration can shift the binding mechanism between conformational selection and induced fit. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(28), 10197–10202. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407545111

Overcoming the Shortcomings of Peptide-Based Therapeutics. (2022). Future Drug Discovery. https://doi.org/10.4155//fdd-2022-0005

Vikram Gaikwad, Choudhury, A. R., & Chakrabarti, R. (2025). Microscopic Insights into the Solvation of Stapled Peptides–A Case Study of p53-MDM2. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 129(29), 7499–7510. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcb.5c03100

Vogt, A. D., & Cera, E. D. (2012). Conformational Selection or Induced Fit? A Critical Appraisal of the Kinetic Mechanism. Biochemistry, 51(30), 5894–5902. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi3006913

Wang, J., Do, H. N., Koirala, K., & Miao, Y. (2023). Predicting Biomolecular Binding Kinetics: A Review. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, 19(8), 2135–2148. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jctc.2c01085

Wang, X., Ni, D., Liu, Y., & Lu, S. (2021). Rational Design of Peptide-Based Inhibitors Disrupting Protein-Protein Interactions. Frontiers in Chemistry, 9, 682675–682675. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2021.682675

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.