Molecular Docking vs. QSAR: How Smart Computing Shapes ADMET Decisions

Why ADMET Needs a Better Plan

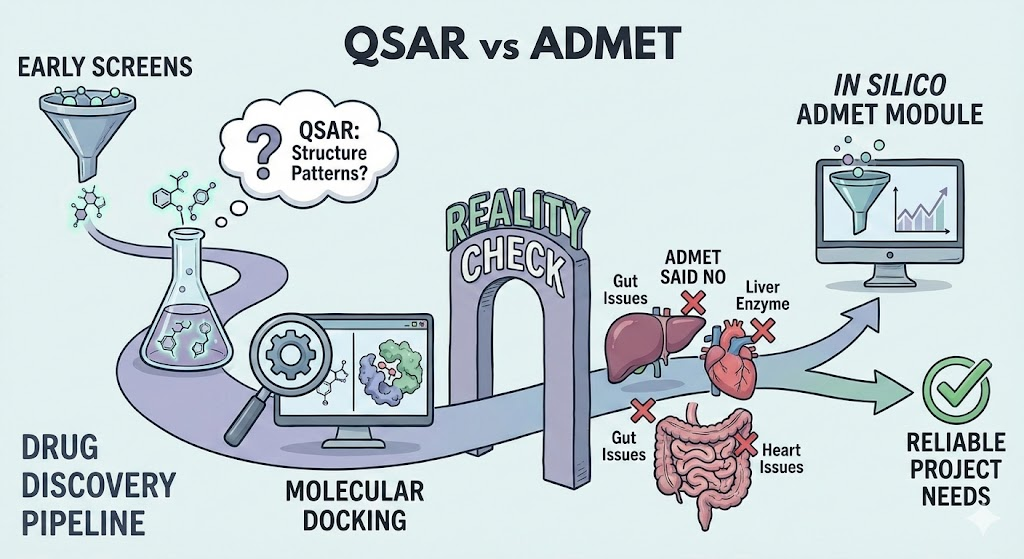

Most drug projects begin with bright hopes and a pile of molecules that look good on paper. Then reality walks in. A compound that seemed like a star in early screens may vanish in the gut, stick to plasma proteins, clog a liver enzyme, or cause heart issues no team wants to explain in a meeting. Anyone who has worked in discovery knows this moment. The drug was fine until ADMET said no.

ADMET profiling has moved from a late filter to a front-line requirement in modern drug design. Poor PK and unexpected toxicity were once responsible for nearly half of all failures in the clinic. This pushed research teams toward early in silico testing, allowing them to flag the weak links before money and months are spent on long wet-lab cycles. Yet even with this shift, experimental ADMET work remains slow and costly when dealing with wide chemical space.

This is where strong computational screening becomes essential. The focus of this work is to inspect two major approaches used in current pipelines: QSAR, which studies patterns in chemical structure, and molecular docking, which studies how a molecule might fit in a protein pocket. These tools are often spoken of as rivals, but in practice they answer different questions and fail in different ways. Used with care, they fill the gaps in each other’s blind spots.

The goal here is to break down these methods, highlight their uses across common ADMET endpoints, and prepare the ground for a full benchmarking study. This includes decisions on datasets, proper validation, and the design of mixed models that combine QSAR features with docking outputs. The final aim is to give a clear path for building a reliable ADMET module that can support real project needs.

2. Theoretical Paradigms in Computational Modeling

To design a valid set of experiments for an ADMET module, one must first deconstruct the theoretical axioms that govern QSAR and molecular docking. The fundamental distinction lies in their approach to biological reality: QSAR is an inductive process relying on statistical inference from known data, while molecular docking is a deductive process simulating physical interactions based on first principles and empirical scoring.

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.

2.1 Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

QSAR is predicated on the central axiom of chemoinformatics: structural similarity implies functional similarity. This principle asserts that the biological activity or physicochemical property of a molecule is a deterministic mathematical function of its molecular structure. The objective of QSAR modeling is to approximate this function (f) by mapping a vector of calculated molecular descriptors (D) to a biological endpoint

Pi= f(Di1, Di2,...,Din) + ϵ

Where Pi is the property of molecule i, D represents the vector of descriptors, and ϵ represents the error term.

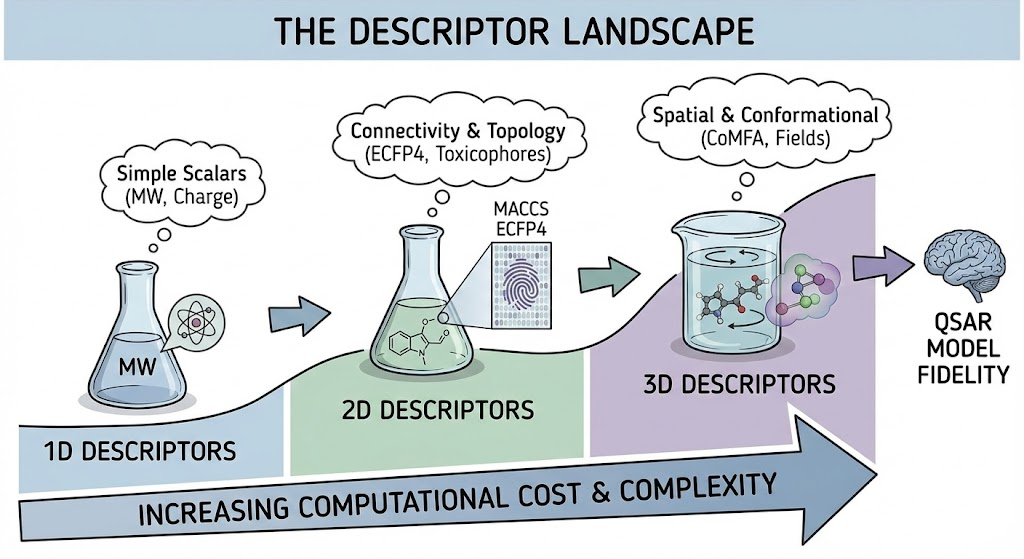

The Descriptor Landscape The fidelity of a QSAR model is intrinsically limited by the information content of its descriptors. In the context of ADMET prediction, descriptors are generally categorized into hierarchies of increasing complexity:

• 1D Descriptors: Scalar values representing bulk properties, such as Molecular Weight (MW), atom counts, and total charge. These are computationally trivial to generate but lack topological context.

• 2D Descriptors: Topological indices that encode the connectivity of the molecule. This includes graph invariants (e.g., Wiener index, Balaban index) and molecular fingerprints (e.g., MACCS keys, ECFP4). Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) are particularly dominant in ADMET modeling because they capture circular substructural environments, which often correspond to "toxicophores" or metabolic liabilities.

• 3D Descriptors: These encode the spatial arrangement of atoms, capturing stereochemistry, molecular fields, and potential pharmacophoric points (e.g., CoMFA, CoMSIA fields). While theoretically richer, 3D descriptors introduce dependency on conformation generation, significantly increasing computational cost and noise if the bioactive conformation is unknown.

Statistical and Machine Learning Engines The mathematical "engine" driving QSAR has evolved substantially. Early approaches relied on Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) and Partial Least Squares (PLS), which assume linearity between descriptors and activity. While interpretable, these methods often fail to capture the complex, non-linear landscapes of toxicity and metabolism. Modern ADMET modules predominantly utilize non-linear Machine Learning (ML) algorithms: • Random Forest (RF) and Gradient Boosting (XGBoost): These ensemble methods are currently the "gold standard" baselines for ADMET benchmarking. They are robust to noise, handle high-dimensional feature spaces (like fingerprints) effectively, and provide measures of feature importance. • Support Vector Machines (SVM): Effective for defining decision boundaries in high-dimensional spaces, particularly for binary classification tasks like "Toxic/Non-Toxic". • Deep Learning (GNNs): Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs), such as ChemProp, represent the frontier. Instead of using pre-calculated descriptors, these models learn optimal representations directly from the molecular graph during training.

2.2 Molecular Docking

Molecular docking is a structure-based simulation technique that predicts the preferred orientation (pose) and binding affinity of a ligand to a macromolecular target. In the context of ADMET, docking is restricted to endpoints mediated by specific proteins, such as metabolic enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4, CYP2D6), transporters (e.g., P-gp/MDR1), and specific toxicity targets (e.g., hERG, Androgen Receptor).

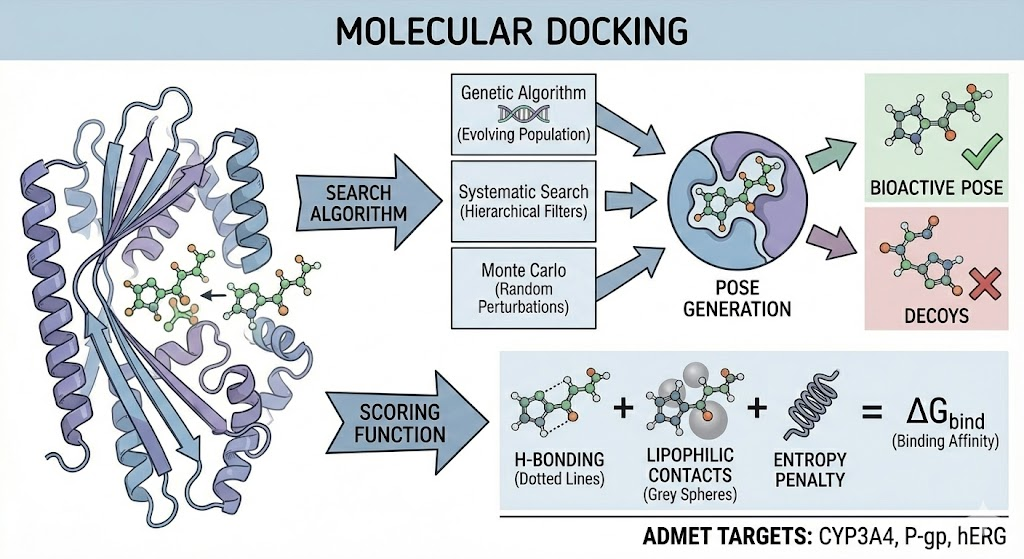

The Mechanics The docking process involves two coupled components:

a. Search Algorithm: This component explores the conformational space of the ligand (and occasionally the receptor). It navigates degrees of freedom including translation, orientation, and torsion angles of rotatable bonds. Common algorithms include:

◦ Genetic Algorithms (Lamarckian GA): Used by AutoDock, this method evolves a population of ligand conformations over generations to minimize energy.

◦ Systematic Search: Used by Glide, this method exhaustively explores conformational space using hierarchical filters.

◦ Monte Carlo Simulated Annealing: Used by Rosetta and Vina, this method makes random perturbations and accepts/rejects them based on the Metropolis criterion.

b. Scoring Function: This component evaluates the generated poses to estimate the free energy of binding (ΔG bind). The accuracy of docking is entirely dependent on the scoring function's ability to discriminate between the correct bioactive pose and decoys.

◦ Empirical Scoring Functions: Calibrated against experimental affinity data (e.g., PDBbind). They sum contributions from terms like hydrogen bonding, lipophilic contact, and entropy penalties (e.g., GlideScore, AutoDock Vina).

◦ Knowledge-Based Potentials: Derived from statistical analysis of interatomic contact frequencies in large crystal structure databases (e.g., DrugScore).

The Challenge of Flexibility A critical limitation of docking in ADMET is protein flexibility. While standard docking treats the receptor as a rigid body, ADMET targets like CYP450s and P-glycoprotein exhibit significant plasticity (Induced Fit). A ligand might bind to an "open" conformation of CYP3A4 that is structurally distinct from the "closed" crystal structure. Rigid docking often produces false negatives in these scenarios, necessitating advanced techniques like Induced-Fit Docking (IFD) or Molecular Dynamics (MD) refinement, which drastically increase computational cost.

3. Comparative Analysis by ADMET Endpoint

To build an effective ADMET module, one cannot simply choose "QSAR" or "Docking" universally. The optimal strategy is endpoint-dependent. The following analysis evaluates the performance and suitability of each method across the major categories of the ADMET spectrum.(ADMET Property Prediction through Combinations of Molecular Fingerprints, 2023)

3.1 Absorption and Distribution (A/D)

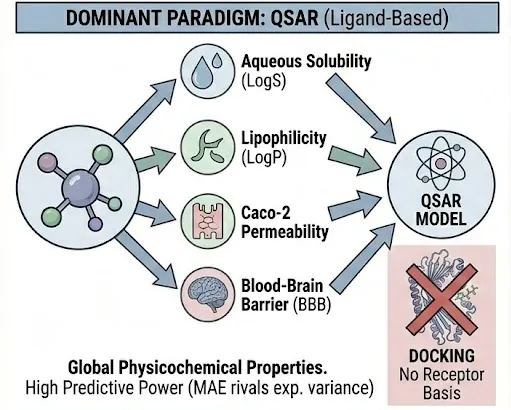

Dominant Paradigm: QSAR (Ligand-Based)

Properties such as Aqueous Solubility (LogS), Lipophilicity (LogP), Caco-2 Permeability, and Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) penetration are largely governed by the global physicochemical nature of the molecule rather than a specific lock-and-key interaction with a single protein pocket.(ADMET Benchmark Group, 2025)

- Solubility & Lipophilicity: These are thermodynamic equilibrium properties determined by solvation energy and crystal lattice energy. Molecular docking has no theoretical basis here, as there is no "solubility receptor." QSAR models, particularly those using descriptors like LogP, Molecular Weight, and Topological Polar Surface Area (TPSA), are the industry standard. Deep learning models (e.g., ChemProp) trained on datasets like AqSolDB (approx. 10,000 compounds) have achieved Mean Absolute Errors (MAE) rivaling experimental variance.

- Permeability (Caco-2/PAMPA): While transporters play a role in intestinal absorption, passive diffusion is often the rate-limiting step for the majority of drug-like space. QSAR models utilizing TPSA and hydrogen bond counts are highly predictive. Docking is only relevant if one specifically suspects carrier-mediated transport (e.g., PepT1) is the primary absorption mechanism, which is a minority case.

- Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB): Penetration is a function of lipid solubility, size, and P-gp efflux liability. While docking to P-gp can inform the efflux component (discussed below), the overall BBB status is best predicted by classification QSAR models. Benchmarks on the TDC BBB dataset (~2,000 compounds) show that classical Random Forest models using 2D fingerprints often perform as well as complex GNNs, providing a robust baseline for any new module.(Stratiichuk et al., 2025)

3.2 Metabolism (M): The Cytochrome P450 Battleground

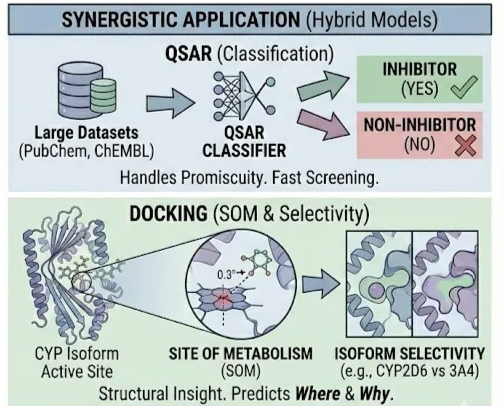

Status: Synergistic Application (Hybrid Models)

The metabolism of xenobiotics is primarily mediated by the Cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily, with isoforms 3A4, 2D6, 2C9, 1A2, and 2C19 accounting for >75% of drug metabolism. This domain represents the most fertile ground for comparing and combining docking and QSAR.(Palestro et al., 2014)

The Case for QSAR in Metabolism

For high-throughput profiling, QSAR is the workhorse. Large public datasets (e.g., PubChem, ChEMBL) contain bioactivity data for thousands of compounds against major CYP isoforms.

- Classification: Predicting if a molecule is an Inhibitor or Non-inhibitor. QSAR models trained on these binary labels are fast and effective. For example, classifiers for CYP2C9 and CYP2D6 inhibition in the TDC benchmark group utilize ~12,000 data points each, allowing Random Forest and GNN models to learn the "chemical signature" of inhibition without needing to solve the binding pose.

- Strengths: Handles the "promiscuity" of CYPs well by learning features of diverse substrates. Computationally inexpensive, enabling the screening of millions of compounds.(Jain, 2025)

The Case for Docking in Metabolism

QSAR models generally fail to predict the Site of Metabolism (SOM) i.e., where on the molecule the oxidation will occur. This is where docking excels.

- SOM Prediction: By docking a ligand into the heme-containing active site of a CYP isoform (e.g., CYP2D6 PDB 3QM4 or CYP3A4 PDB 5VCC), one can measure the distance between the heme iron and potential metabolic sites (e.g., methyl groups, aromatic rings). The geometry of the pose provides a mechanistic hypothesis for the metabolic product.

- Isoform Selectivity: Docking can rationalize why a drug is metabolized by CYP2D6 (narrow, acidic pocket) versus CYP3A4 (large, flexible, hydrophobic pocket). This structural insight is invaluable for lead optimization when chemists attempt to "dial out" metabolic liability by modifying specific steric features.

Failure Modes: The large, plastic active site of CYP3A4 is a notorious challenge for rigid docking. Standard AutoDock Vina or Glide protocols often fail to capture the binding of large ligands that induce significant conformational changes in the protein. In such cases, QSAR models often outperform docking in pure affinity prediction because they implicitly "learn" the flexibility from the training data.(Trott & Olson, 2009)

3.3 Transporters: The P-glycoprotein Challenge

Status: QSAR Dominance due to Structural Complexity

P-glycoprotein (P-gp/MDR1) is a broad-spectrum efflux pump responsible for multidrug resistance. It has a massive, flexible binding cavity (~6000 ų) that can accommodate multiple ligands simultaneously, making it a nightmare for standard docking protocols.(Koirala et al., 2025)

- Docking Limitations: The "polyspecificity" of P-gp means standard scoring functions struggle to discriminate between binders and non-binders, as the binding energy landscape is flat and defined by vague hydrophobic interactions rather than specific hydrogen bonds. While flexible docking protocols (e.g., using induced-fit or ensemble docking) have shown some utility, they are computationally too expensive for routine screening modules.

- QSAR Utility: Due to these structural difficulties, ligand-based QSAR classifiers (Substrate vs. Non-substrate; Inhibitor vs. Non-inhibitor) remain the industry standard. Dataset sizes for P-gp in TDC are modest (~1,200 compounds), but sufficient for Random Forest models to achieve usable accuracy (AUROC > 0.85).

3.4 Toxicity: hERG and Beyond

Status: High-Value Target for Hybrid Modeling

hERG Channel Inhibition: Blockage of the hERG potassium channel is a primary cause of drug-induced QT prolongation and fatal arrhythmias. It is a regulatory hard-stop.

- QSAR: The primary screen. Models trained on electrophysiology patch-clamp data (IC50) are standard. However, simple QSAR sometimes struggles with "activity cliffs"—where a small structural change causes a massive safety shift.(Creanza et al., 2021)

- Docking: Recent cryo-EM structures of hERG (e.g., PDB 5VA1) have revolutionized this field. Docking reveals that many blockers bind within the central pore via pi-stacking interactions with residues like Tyr652 and Phe656.(Maroua Fattouche et al., 2024)

- Hybrid Advantage: Benchmarking studies have demonstrated that integrating docking scores (specifically the interaction energy with key pore residues) as features into a QSAR model (Structure-Based QSAR) significantly improves predictive accuracy over 2D descriptors alone. This "hybrid" approach captures both the general chemical properties (QSAR) and the specific steric fit into the channel pore (Docking).

| ADMET Endpoint | Primary Method | Secondary Method | Key Limitation of Secondary | Recommended Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility (LogS) | QSAR | None | No specific target | QSAR (GNN or RF) |

| Permeability (Caco-2) | QSAR | Docking | Only for specific carriers | QSAR (RF with TPSA/MW) |

| Metabolism (CYP450) | QSAR | Docking | Protein flexibility (Induced fit) | QSAR for screening; Docking for SOM |

| Clearance (CLint) | QSAR | PBPK | Requires Vmax/Km inputs | QSAR -> PBPK Integration |

| hERG Toxicity | QSAR | Docking | Scoring accuracy | Hybrid (QSAR + Docking Features) |

| P-gp Efflux | QSAR | Docking | Huge, flexible binding site | QSAR (Classification) |

| Mutagenicity (Ames) | QSAR | None | Target complexity (DNA/Enzymes) | QSAR (Structural Alerts) |

Table. 1 Summary of Methodological Applicability

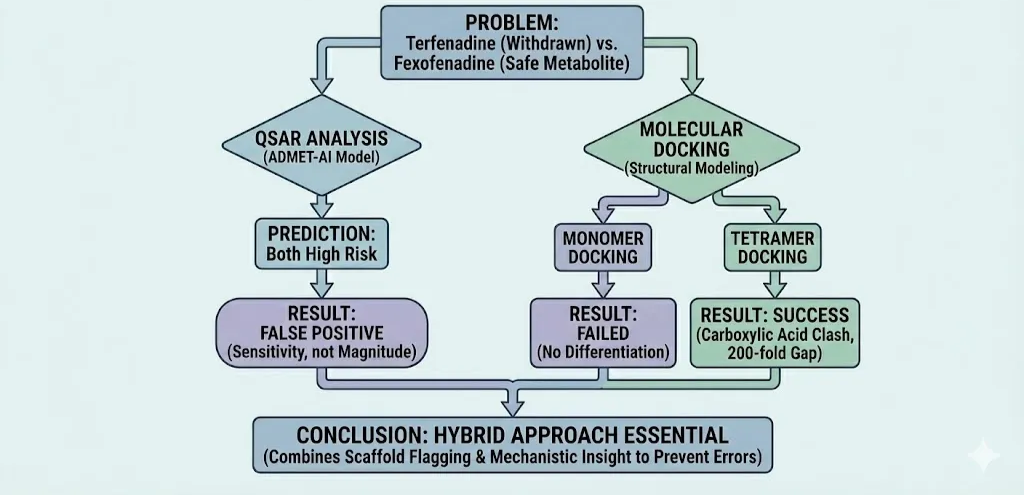

4. Case Study: Navigating the hERG Activity Cliff of Terfenadine vs. Fexofenadine

To illustrate the practical friction between QSAR and structural modeling, we examined one of the most famous "activity cliffs" in pharmaceutical history: the relationship between the withdrawn antihistamine Terfenadine and its safe metabolite, Fexofenadine.

Terfenadine was withdrawn from the market in 1997 due to fatal arrhythmias caused by potent hERG channel blockade. Fexofenadine, which differs structurally by only a single carboxylic acid group on the terminal benzene ring, exhibits a 200-fold reduction in hERG affinity and is safe for daily clinical use.

We subjected both molecules to the ADMET-AI QSAR model (Swanson et al., 2024) and compared these predictions against experimental IC50 data and structural literature.

4.1. The QSAR Blind Spot: Sensitivity vs. Magnitude

The ADMET-AI model successfully identified the trend but failed to capture the magnitude of the safety margin.

- Terfenadine: Predicted hERG probability of 97.7% (High Risk).

- Fexofenadine: Predicted hERG probability of 68.2% (High Risk).

While the model correctly ranked Terfenadine as the more toxic entity (a 29.5% probability gap), it still classified Fexofenadine as a "high risk" compound. In a binary screening funnel, both molecules might have been discarded.

This stands in stark contrast to experimental reality. Electrophysiology data (Kamiya et al., 2008; Scherer et al., 2002) establishes Terfenadine’s IC50 at 15–56 nM, whereas Fexofenadine’s IC50 shifts dramatically to ~4,590 nM.

Why did QSAR struggle? The failure is rooted in the descriptors. The molecules are physicochemical twins: they share a ~30 Da molecular weight difference and very similar lipophilicity profiles (LogP 6.45 vs 5.51). Because the ADMET-AI model relies on learned patterns from 2D and 3D descriptors, it views these two molecules as structurally synonymous. It sees the "toxicophore" (the central piperidine/phenyl motif) in both, but cannot fully weigh the subtle electronic effect of the carboxylic acid that neutralizes the toxicity.

4.2. The Structural Imperative: The Tetramer Trap

If QSAR lacks the resolution to distinguish these molecules, molecular docking should theoretically fill the gap. However, this case study highlights a critical dependency in structure-based design: Biological Assembly.

Preliminary docking of both ligands into a single hERG subunit (monomer) failed to reproduce the experimental 200-fold affinity gap. The scoring functions could not differentiate the binding energies significantly.

This aligns with findings by Vaz et al. (2011) and Wu et al. (2021), which demonstrate that accurate hERG predictions require the full tetrameric pore assembly. The toxicity of Terfenadine arises from specific pi-stacking interactions with Phe656 and Tyr652 within the central pore. The addition of the carboxylic acid in Fexofenadine creates an electrostatic penalty and steric clash only when the channel is modeled in its complete tetrameric state.

Summary

This case study perfectly encapsulates the "Hybrid" argument.

- QSAR correctly flagged the scaffold as dangerous but lacked the nuance to "clear" the safe metabolite.

- Docking holds the potential to explain the mechanism (the carboxylic acid clash), but only if the simulation environment (the tetramer) accurately reflects biological reality.

Relying on either method in isolation would have resulted in a false positive (killing a safe drug via QSAR) or a potential false negative (missing the toxicity via monomer-based docking).

Conclusions and Strategic Recommendations

For the development of a robust internal ADMET module, the "Docking vs. QSAR" debate should be reframed as a "Tiered Integration" strategy. The evidence suggests neither tool is sufficient alone, but together they form a comprehensive filter.

Strategic Recommendations

- Backbone with QSAR: The primary engine of the module should be QSAR. It is the only method scalable to large libraries and applicable to all endpoints (solubility, permeability, global toxicity).

- Use Random Forest as the Benchmark: Do not assume Deep Learning is necessary. Start with Random Forest (ECFP4). Only deploy ChemProp/GNNs if they demonstrate a statistically significant improvement (>0.02 AUROC) on Scaffold Splits. Complexity without gain is technical debt.

- Deploy Hybrid Models for High-Risk Targets: For critical safety endpoints like hERG and major metabolic liabilities like CYP3A4, implement a hybrid pipeline. Dock the compounds, extract the scores, and use them as features. This adds mechanistic resilience to the statistical predictions.

- Rigorous Validation: Reject any model validated solely on random splits. Implement scaffold splitting and use imbalance-aware metrics (AUPRC, MCC) to ensure the module provides value in real-world discovery campaigns.

References

ADMET Benchmark Group. (2025). TDC. https://tdcommons.ai/benchmark/admet_group/overview/

ADMET property prediction through combinations of molecular fingerprints. (2023). Ar5iv. https://ar5iv.labs.arxiv.org/html/2310.00174

Creanza, T. M., Delre, P., Ancona, N., Lentini, G., Saviano, M., & Mangiatordi, G. F. (2021a). Structure-Based Prediction of hERG-Related Cardiotoxicity: A Benchmark Study. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 61(9), 4758–4770. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00744

Creanza, T. M., Delre, P., Ancona, N., Lentini, G., Saviano, M., & Mangiatordi, G. F. (2021b). Structure-Based Prediction of hERG-Related Cardiotoxicity: A Benchmark Study. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 61(9), 4758–4770. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00744

Farid Amellal, & Billette, J. (1996). Selective Functional Properties of Dual Atrioventricular Nodal Inputs. Circulation, 94(4), 824–832. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.94.4.824

Jain, A. (2025, January 5). Undersampling, Oversampling and SMOTE, Ensemble Method and Cost Sensitive Learning techniques for…. Medium. https://medium.com/@abhishekjainindore24/undersampling-oversampling-and-smote-ensemble-mehtod-and-cost-sensitive-learning-techniques-for-08efb557ec68

Kamiya, K., Niwa, R., Morishima, M., Haruo Honjo, & Sanguinetti, M. C. (2008). Molecular Determinants of hERG Channel Block by Terfenadine and Cisapride. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences, 108(3), 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1254/jphs.08102fp

Knape, K., Linder, T., Wolschann, P., Beyer, A., & Stary-Weinzinger, A. (2011). In silico Analysis of Conformational Changes Induced by Mutation of Aromatic Binding Residues: Consequences for Drug Binding in the hERG K+ Channel. PLoS ONE, 6(12), e28778. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0028778

Koirala, M., Yan, L., Mohamed, Z., & DiPaola, M. (2025). AI-Integrated QSAR Modeling for Enhanced Drug Discovery: From Classical Approaches to Deep Learning and Structural Insight. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(19), 9384. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms26199384

Maroua Fattouche, Salah Belaidi, Oussama Abchir, Walid Al-Shaar, Younes, K., Muneerah Mogren Al-Mogren, Samir Chtita, Soualmia, F., & Majdi Hochlaf. (2024). ANN-QSAR, Molecular Docking, ADMET Predictions, and Molecular Dynamics Studies of Isothiazole Derivatives to Design New and Selective Inhibitors of HCV Polymerase NS5B. Pharmaceuticals, 17(12), 1712–1712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph17121712

Palestro, P. H., Gavernet, L., Estiu, G. L., & Bruno, L. E. (2014). Docking Applied to the Prediction of the Affinity of Compounds to P-Glycoprotein. BioMed Research International, 2014, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/358425

Scherer, C. R., Lerche, C., Decher, N., Dennis, A. T., Maier, P., Ficker, E., Busch, A. E., Bernd Wollnik, & Steinmeyer, K. (2002). The antihistamine fexofenadine does not affect IKr currents in a case report of drug‐induced cardiac arrhythmia. British Journal of Pharmacology, 137(6), 892–900. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjp.0704873

Stratiichuk, R., Shevchuk, N., Kyrylenko, R., Vozniak, V., Koleiev, I., Voitsitskyi, T., Husak, V., Ostrovsky, Z., Khropachov, I., Starosyla, S., Yesylevsky, S., & Nafiev, A. (2025). Improving ADMET prediction with descriptor augmentation of Mol2Vec embeddings. https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.07.14.664363

Swanson, K., Walther, P., Leitz, J., Mukherjee, S., Wu, J. C., Shivnaraine, R. V., & Zou, J. (2024). ADMET-AI: a machine learning ADMET platform for evaluation of large-scale chemical libraries. Bioinformatics, 40(7). https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btae416

Trott, O., & Olson, A. J. (2009). AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 31(2), 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcc.21334

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.