Molecular Docking in Drug Discovery

Imagine spending over a decade and billions of dollars chasing a single medicine, only to see most candidates fail before they ever reach a patient’s hands. That’s the reality of drug development today. On average, it takes 12 to 15 years and billion of dollars to bring a new drug from the lab to the pharmacy shelf. Out of the thousands of compounds discovered, maybe one will make it all the way through. What if a computational method could accelerate this timeline from years to weeks?

Molecular Docking has revolutionized how we approach protein-ligand interactions in structure-based drug design. This computational tool has become fundamental in modern drug discovery pipelines, enabling the virtual screening of millions of compounds before expensive experimental validation. As pharmaceutical R&D spending reached $260 billion in 2023, docking serves as a cost-effective filter in the early stages of drug development.

What is Molecular Docking

Picture a scientist staring at a 3D model of a protein on their computer screen. Somewhere on that protein lies a tiny pocket, just the right size for a molecule that could become tomorrow’s life-saving drug. But which molecule will fit? Testing them one by one in the lab would take years.

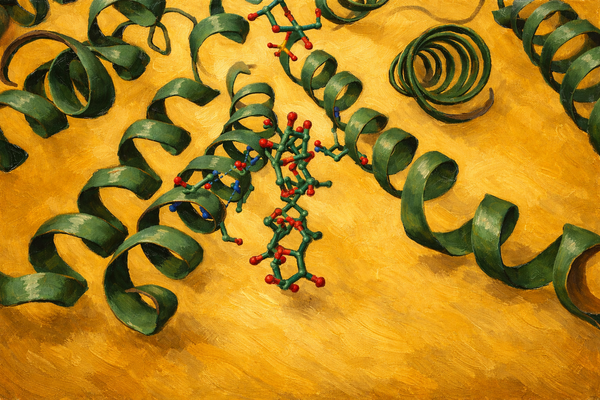

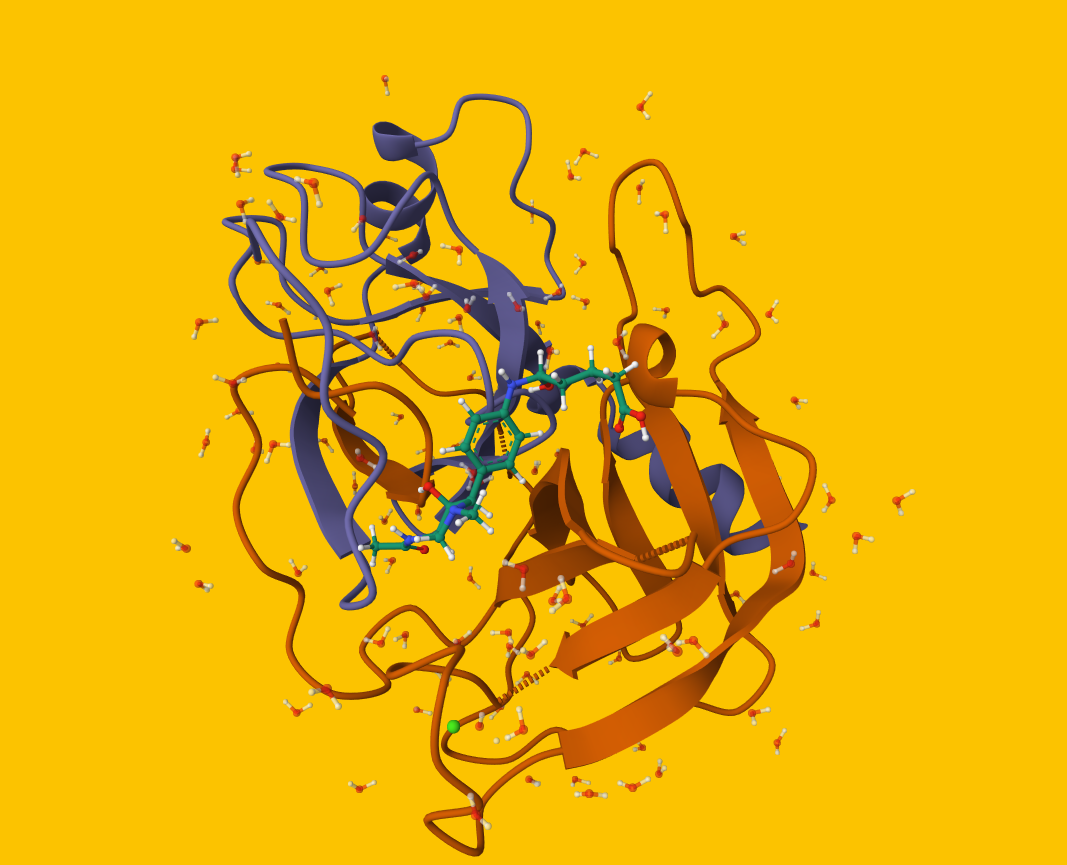

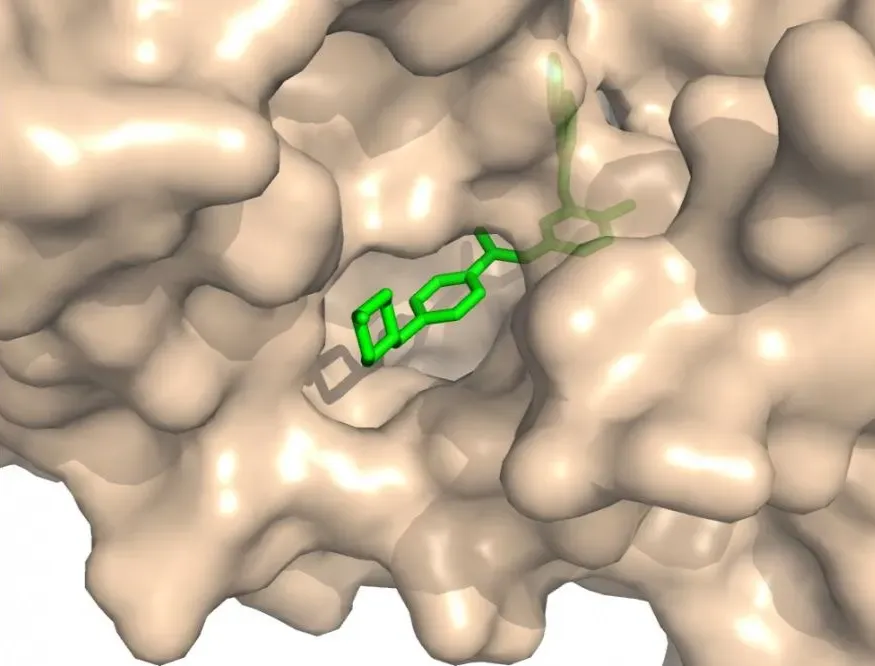

This is where molecular docking comes in. It is a computational method that seeks to predict how two or more molecules will bind to form a stable complex. In the most common scenario, a small molecule, referred to as the "ligand," is docked into the binding site of a large biomolecule, the "receptor," which is typically a protein or a nucleic acid. Molecular Docking heavily relies on structure-based drug design and therefore needs high resolution experimental structures obtained from techniques like X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy.

This process has two primary and interconnected goals:

- Predicting the binding pose: This is the geometric challenge of docking. The objective is to determine the most favorable 3D orientation of the ligand within the receptor's binding site. But here’s the tricky part: the ligand doesn’t just drop in like a rigid Lego block. It can flex around its bonds, changing shape until it finds a position where everything clicks into place like hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts stabilizing the complex.

- Affinity Prediction (Scoring): This is the energetic challenge. The goal here is to estimate the strength of the interaction between the ligand and the receptor, quantified as the binding free energy. This is represented by a "docking score," a numerical value calculated by a scoring function. By convention, a more negative (or lower) score indicates a stronger, more stable predicted interaction, suggesting a higher binding affinity.

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.

The Docking Algorithm

If molecular docking were a video game, the docking algorithm would be the “engine” running under the hood. It decides how the pieces move around and how the game keeps score. Every docking program relies on two things: a way to search (to figure out how a ligand might fit into a receptor) and a way to score (to judge which fits are actually good).

Sampling (The Search Algorithm)

The search algorithm is responsible for exploring the vast "conformational space" of the system. This space includes every possible way a ligand can sit inside the receptor, plus all the shapes it can adopt as its bonds rotate. The combinations are essentially astronomical, which makes brute-force searching impossible.

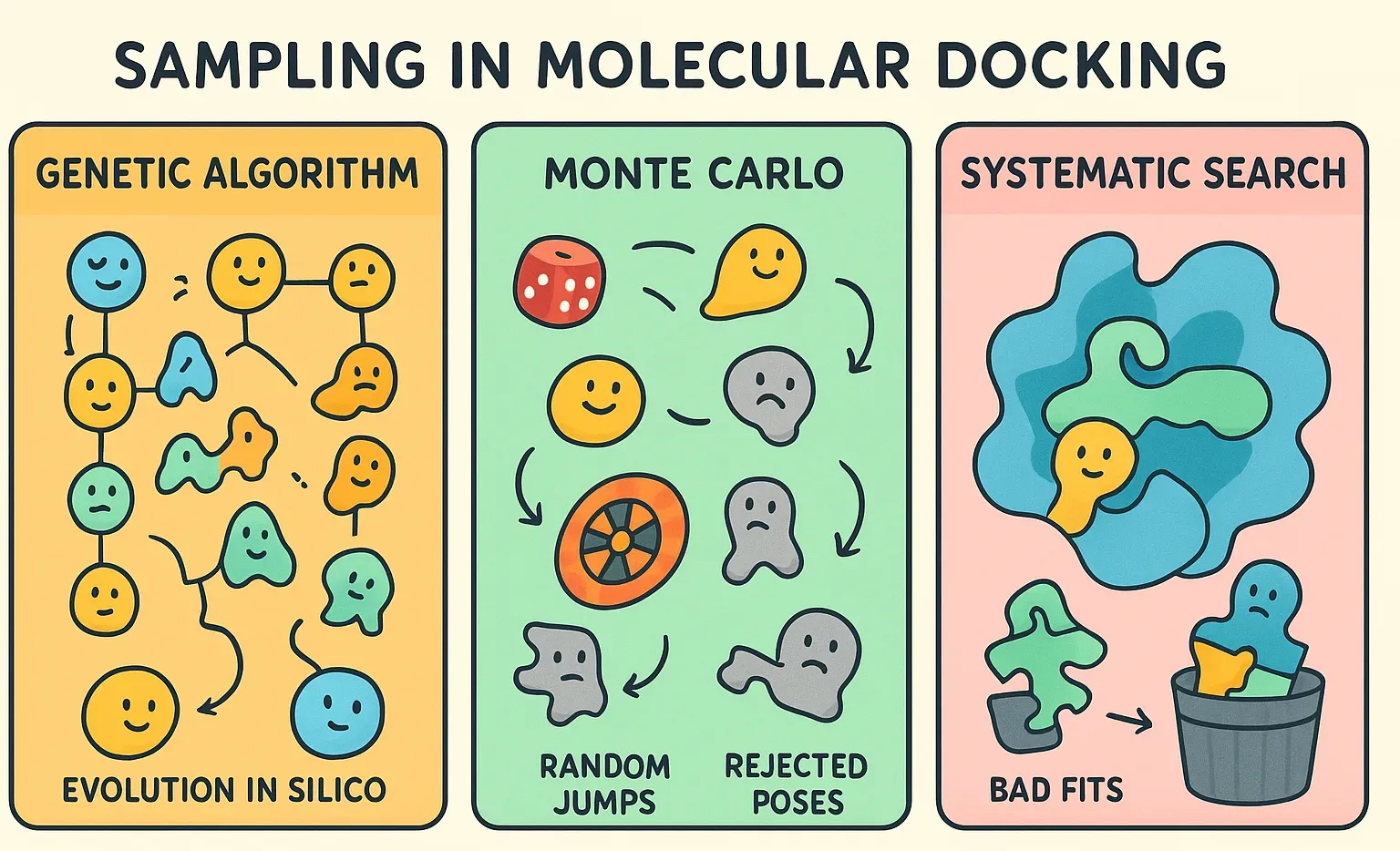

To tackle this, docking programs use smart search algorithms that balance speed with accuracy. Instead of checking every possibility, they explore the most promising regions of the space. Common strategies include:

- Genetic Algorithms: Used by programs like AutoDock and GOLD, these algorithms mimic principles of biological evolution. The idea borrows from evolution: start with a “population” of random ligand poses, then let them evolve. Poses undergo mutation (small random tweaks), crossover (mixing features of two good poses), and selection (keeping the strongest fits). With each generation, weaker poses drop out while stronger ones survive, and therefore, in the end an optimal binding pose.

- Monte Carlo Methods: It involves making random changes to the ligand's position, orientation, or conformation. Each new pose is evaluated, and it is accepted or rejected based on a criterion that favors lower-energy states.

- Systematic Searches: The algorithm doesn’t rely on randomness. Instead, it tries to cover the conformational space in an orderly way. A common trick is to split the ligand into smaller fragments and place them one by one into the binding site, gradually building up the full molecule. This helps manage complexity, but the number of possibilities still grows fast, therefore, pruning strategies are used to cut off bad fits early.

Scoring Function

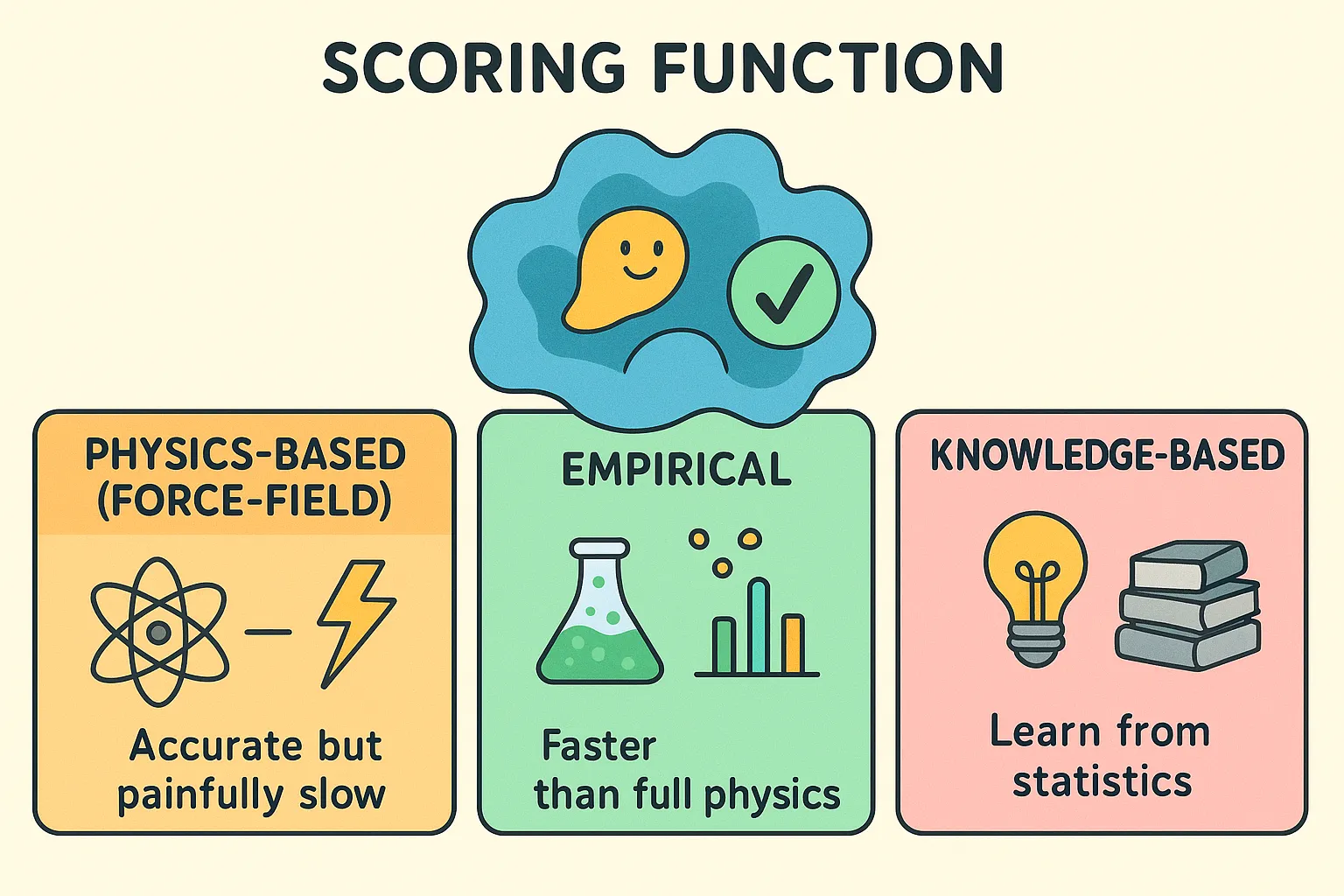

It is the mathematical engine that estimates how strongly a ligand binds in a given pose. It plays two key roles. During the search, it gives quick feedback whether the current pose is better than the last pose and, in the end, it ranks all the generated poses to highlight the most likely binding mode. Without scoring, docking would generate endless possibilities. Scoring functions are usually approximations and are usually of three types:

- Physics-Based (Force-Field): They apply laws of physics to estimate binding strength which relies on several factors such as energies from van der Waals forces, electrostatics, and molecular force fields such as CHARMM or AMBER. Accurate but painfully slow.

- Empirical: Based on experimental data, these functions use a weighted sum of simple terms such as hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and penalties for rotational flexibility. They’re faster than full physics and tuned to match real-world results.

- Knowledge-Based: Instead of physics or experiments, these functions learn from statistics. By analyzing thousands of known protein–ligand structures, they assign “potentials” to atomic contacts: the more often an interaction shows up in nature, the more favorable it’s assumed to be.

Docking lives on the trade-off between accuracy and speed. The search has to test millions of ligand poses, which means the scoring function used during sampling must be fast but approximate. This sacrifices physical realism, so the final ranking can’t rely on those scores alone. To handle this, most workflows use a two-stage process: a rapid initial search with simplified scoring to generate candidate poses, followed by more rigorous re-scoring of the top hits. This balance between efficiency and accuracy defines both the strength and the limitation of docking.

Types of Docking

We will briefly differentiate the types of docking in the following basis:

- On the basis of flexibility of the interacting molecules

- On the basis of interacting partners

- On the basis of Binding Site knowledge

Let's understand each of them in proper details:

On the basis of flexibility of the interacting molecules

Under this we got Rigid Docking, Flexible docking, Flexible-Ligand / Rigid-Receptor Docking.

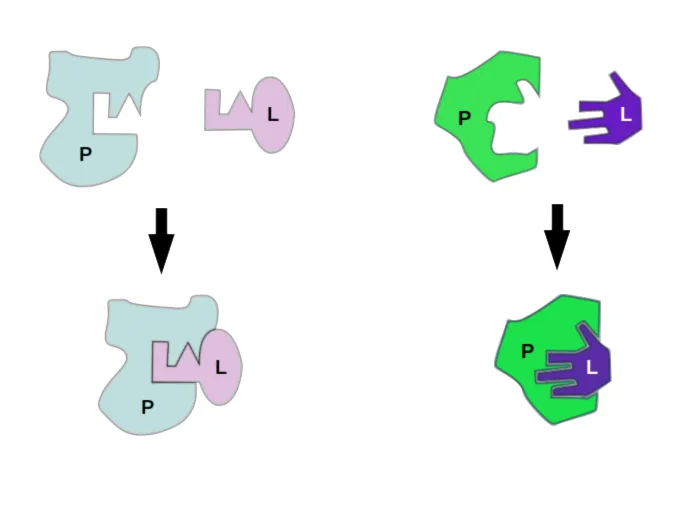

Rigid Docking

Historically, the concept of docking was rooted in the "lock-and-key" model. Protein and ligand as rigid shapes that fit together perfectly. But biological molecules aren’t rigid shapes, they are “dynamic”; they wiggle, bend and adapt to the surrounding environment. The search algorithm only explores the six degrees of translational and rotational freedom to find the best geometric fit. This approach is computationally very fast but is biologically unrealistic for most systems. Primarily used in initial screenings.

Flexible Docking (Flexible Receptor)

The more biologically accurate “induced-fit” or “glove” model recognizes that proteins and ligands aren’t rigid shapes. When they interact, both partners can shift, bend, or twist their conformations to achieve a tighter, more favorable fit. This flexibility is what actually happens in living systems, making induced fit a much closer reflection of reality than the older lock-and-key view. This process is computationally expensive, so it's usually saved for the very end of a docking study to refine the best-looking candidate structures.

Flexible-Ligand / Rigid-Receptor Docking:

This is the most common and widely used approach in drug discovery, especially for large-scale virtual screening. The ligand can rotate around its bonds and adopt different shapes, but the protein is treated as rigid. This makes the model more realistic than rigid–rigid docking while keeping the computational cost reasonable. It is widely used by docking tools like AutoDock Vina and Glide.

On the basis of interacting partners

Under this we have Protein-Ligand Docking, Protein-Protein Docking, Protein-Nucleic Acid Docking.

Protein – Ligand Docking:

The bread and butter of drug discovery. Here the goal is to predict how a small, drug-like molecule fits into a protein pocket. It is central to drug discovery because it supports virtual screening (computer testing of millions of molecules to find promising ones, called “hits”) and lead optimization (improving those hits by tweaking their structure so they bind better and act more like real drugs).

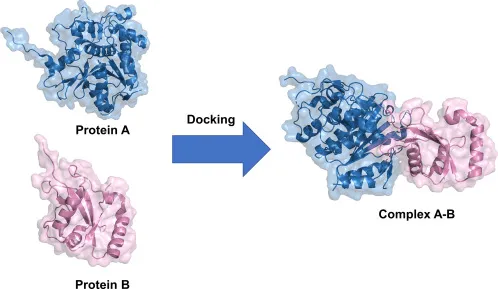

Protein – Protein Docking

Proteins often team up to carry out signaling and cellular functions. Predicting how two proteins fit together is harder than protein – ligand docking as interfaces are larger, flatter, and more flexible, and the binding energies are subtle. Tools like RosettaDock and UDock2 specialize in this tough challenge.

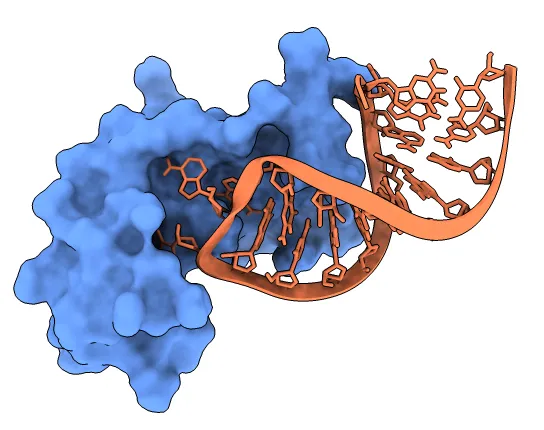

Protein – Nucleic Acid Docking

Unlike proteins, Nucleic Acid docking is hard due to their charged phosphate backbone and groove structures mean you need special handling unlike amino acids chains (proteins). Many important processes such as replication, transcription, and translation relies on it and therefore requires dedicated tools like NPDock and HDOCK.

On the basis of Binding Site knowledge

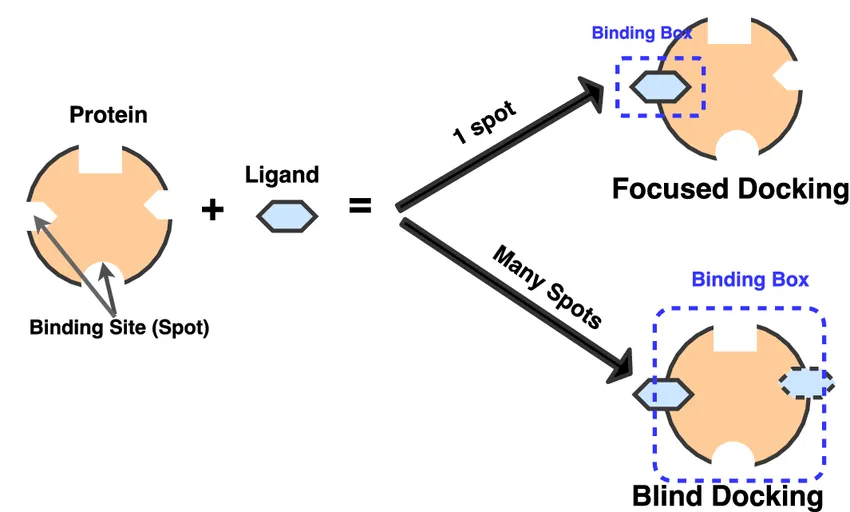

Docking approaches can be grouped by how much we know about the protein’s binding site in advance (using prior experimental results). Under this, we got: Targeted / Focused Docking, Blind Docking.

Targeted/ Focused Docking

Think of this as searching with a flashlight. You already know where the action is, so you shine directly on that spot. Here, the ligand is only tested in a specific region of the protein, usually a well-known active site or binding pocket. Because the search is focused, it’s much faster and easier on computational resources. This is why targeted docking is the go-to method for most drug discovery projects where the binding site is already mapped out.

Blind Docking

Now imagine switching off the flashlight and exploring the entire room in the dark. In blind docking, the ligand is allowed to scan the whole surface of the protein without assumptions about where it might bind. It’s computationally more expensive, but it can uncover hidden or unexpected binding sites, especially allosteric sites, which are alternative pockets that can regulate protein function.

Figure 8 explains clearly, in focused (targeted) docking, the ligand is only tested against a single, predefined binding pocket, making the process fast and precise. In blind docking, the ligand explores the entire protein surface, which is slower but powerful for uncovering unknown or allosteric sites that could become new drug targets.

The selection of a docking method is therefore a critical step in the research process, guided by the specific scientific question. A researcher aiming to quickly screen a million-compound library for potential starting points might choose a fast, flexible-ligand/rigid-receptor approach. Whereas a medicinal chemist seeking to understand the precise binding mode of a high-affinity lead compound would opt for a more computationally intensive flexible docking.

The workflow of Molecular Docking

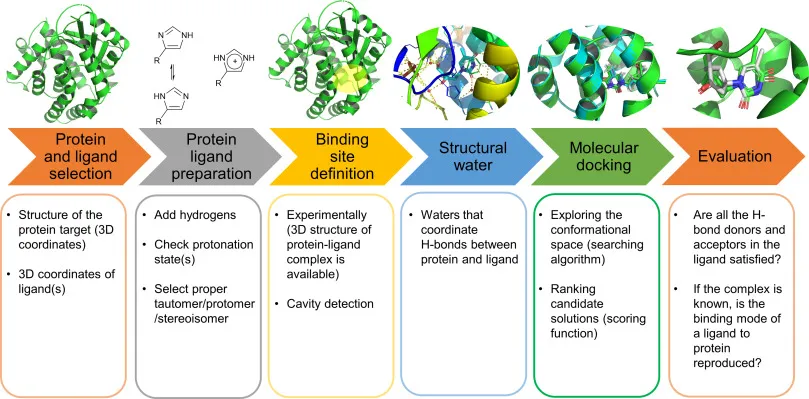

While the theory of docking is complex, the practical workflow has become increasingly accessible thanks to a variety of powerful software tools. Figure 9 sums it up neatly.

- Protein and Ligand SelectionYou start by picking your players: the protein (target) and the small molecule (ligand). Think of it as choosing the lock and the potential key. Structural files from a public repository like Protein Data Bank (PDB) are downloaded.

- Protein - Ligand PreparationBefore docking, both molecules need a cleanup from non-protein atoms like zinc and copper which act as catalysts in biological reactions. Hydrogens are added, protonation states are adjusted on the basis of amino acids states, and the correct molecular form (tautomer, protomer, stereoisomer) is chosen. It’s like sharpening the key so it actually fits.

- Binding Site Definition/Grid BoxWhere on the protein should the ligand try to fit? If you already know the active site, great, you define that cavity and carry out targeted docking. If not, computational tools can scan the entire protein surface to spot potential “pockets” using a three-dimensional grid of points which are used for energy calculation. The box must be large enough to allow the ligand to move and rotate freely within the binding site but not so large as to waste computational effort on irrelevant space.

- Structural WaterWater molecules often disturb the docking process, forming hydrogen bonds between protein and ligand. Therefore, they are usually removed.

- Molecular DockingThis is the actual search. Algorithms explore different orientations and conformations of the ligand inside the binding site. Then, scoring functions rank which poses are most likely to be biologically relevant.

- EvaluationFinally, you check: Do the predicted interactions (like hydrogen bonds) make chemical sense? If experimental data exists, does the docked pose reproduce reality? This step validates whether your “key” actually works in the “lock.” On top of that, you also look at the docking score, the more negative the value, the stronger (and usually better) the predicted binding.

Table 1: Summary of Commonly Used Docking Platforms

| Software | Availability | Core Algorithm | Primary Application | Key Feature |

| AutoDock / Vina | Free (Academic) | Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm / Iterated Local Search | Academic research, general-purpose docking | Widely used, well-documented, Vina is known for its speed and ease of use. |

| Glide | Commercial | Systematic Search + Optimization | High-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) in industry | Highly regarded for its accuracy and robust performance in ranking compounds. |

| GOLD | Commercial | Genetic Algorithm | Lead optimization, handling of protein flexibility | Features multiple scoring functions and advanced options for modeling side-chain flexibility and bridging waters. |

| DOCK6 | Academic License | Anchor-and-Grow Incremental Construction | Academic virtual screening, fragment-based design | A long-standing program from UCSF with a focus on shape complementarity. |

| FlexX | Commercial | Fragment-Based Incremental Construction | Fast virtual screening, scaffold hopping | Builds ligands piece-by-piece into the active site based on interaction patterns. |

| HDOCK | Free (Web Server) | Hybrid Template-based + FFT-based Free Docking | Protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid docking | Specialized for Nucleic Acid- Protein complexes, can use sequences as input. |

A Critical Look at the Limitations of Molecular Docking

Docking generates educated guesses about how molecules might interact, trusting the results blindly would result in a lot of wasted time and money chasing false leads. It's a powerful tool for narrowing down millions of possibilities, but it needs to be validated by real-world experiments.

Scoring Function Problem

The biggest source of error? The scoring function, the formula docking programs use to rank which molecules “fit” best. These functions have to be fast, therefore, they trade off speed with accuracy. They often miss out:

- Entropy calculations: Biological molecules are dynamic, free to wiggle, rotate, bend but when it is docked, it is forced into a single pose. Losing that flexibility costs energy, because the system becomes more ordered. Docking usually can’t fully capture these changes.

- Solvation: Proteins and ligands are surrounded by water in real life. Before docking, one of the steps is to remove water. Making bonds involves displacing water. This is not free energy-wise: displacing water costs energy, and forming new bonds might not fully compensate. Docking scoring functions simplify this, often treating solvent as a background, which can affect the true binding energy of docked complex.

Protein Flexibility

Most standard docking protocols treat the receptor as a single, rigid structure to keep the computational costs low. Proteins are not static. Upon binding a ligand, a protein's active site often undergoes conformational changes, from small side -chain rotations to large-scale domain movements to accommodate the ligand.

Docking Preparation

The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" (GIGO) is paramount in molecular docking. Common mistakes involved:

- Wrong Protonation States: Charges matter. The protonation states of acidic and basic groups on both the ligand and the protein are highly dependent on pH. Docking the wrong form of a molecule leads to wrong predictions due to fundamentally flawed electrostatic calculations.

- Wrong Tautomer: Many organic molecules can exist in multiple tautomeric forms, which are structural isomers that readily interconvert. ****These forms can have different shapes and hydrogen bonding capabilities; docking the wrong tautomer can give poor results.

- Low-Resolution Structures: If your protein structure is fuzzy, docking results will be unreliable. The accuracy of a docking result is limited by the quality of the receptor structure used.

Conclusion

Molecular docking might not be perfect, but it’s still one of the most powerful tools in drug discovery. While docking scores shouldn't be taken as absolute truths, they provide valuable initial guidance for prioritizing compounds and understanding potential binding modes. The key lies in recognizing docking as the first step in a validation pipeline, not the final answer.

To further validate molecular docking predictions, several experimental and computational approaches can be employed. Biochemical assays such as enzyme inhibition studies, binding affinity measurements such as Surface Plasmon Resonance (SRC) and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC).

Molecular dynamics simulations let you watch the docked molecule and protein in motion, checking if the predicted pose is stable. Free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations offer more accurate binding affinity predictions by accounting for entropic effects that standard docking scoring functions miss. And structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies with related compounds help confirm whether the predicted binding mode explains real-world trends in potency and selectivity.

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.