The overlooked role of intrinsic water in protein–ligand binding

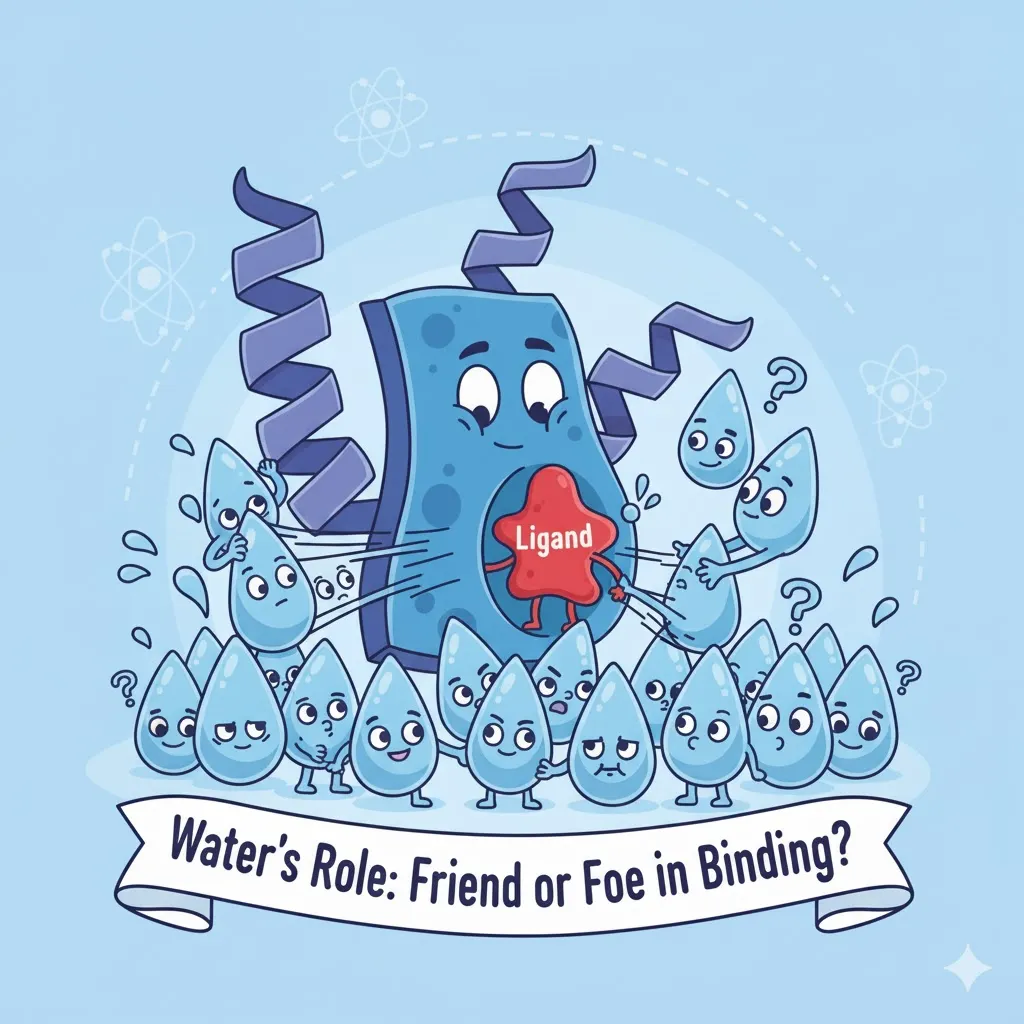

Water is essential for life, that’s something we all know. But beyond keeping us alive, water also shapes how molecules recognize, interact, and bind to each other. In the world of proteins and ligands, it’s far more than just a background solvent.

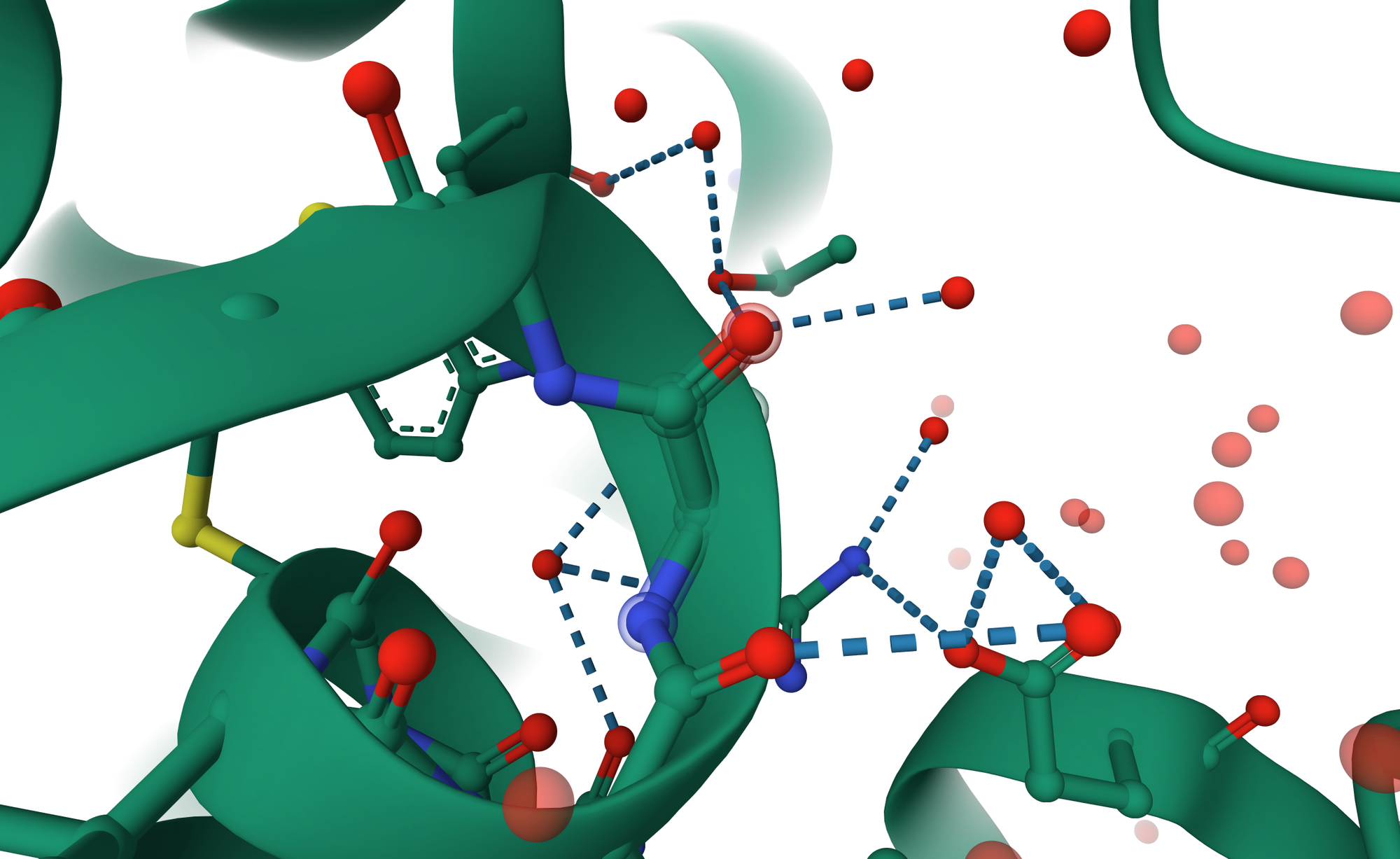

Inside a protein’s binding pocket, water molecules don’t simply float around they take part in the action. They help drugs attach correctly, stabilize the structure, and even influence how strong or weak the binding will be.

In modern drug design, scientists now realize that success isn’t just about pushing water out of the binding site. It’s about understanding how each tiny water molecule behaves, which ones to keep, which to replace, and how they quietly hold everything together. So, how exactly does water manage this backstage role of keeping protein–ligand complexes stable, flexible, and functional? Let’s look closer at the science behind this unsung hero.

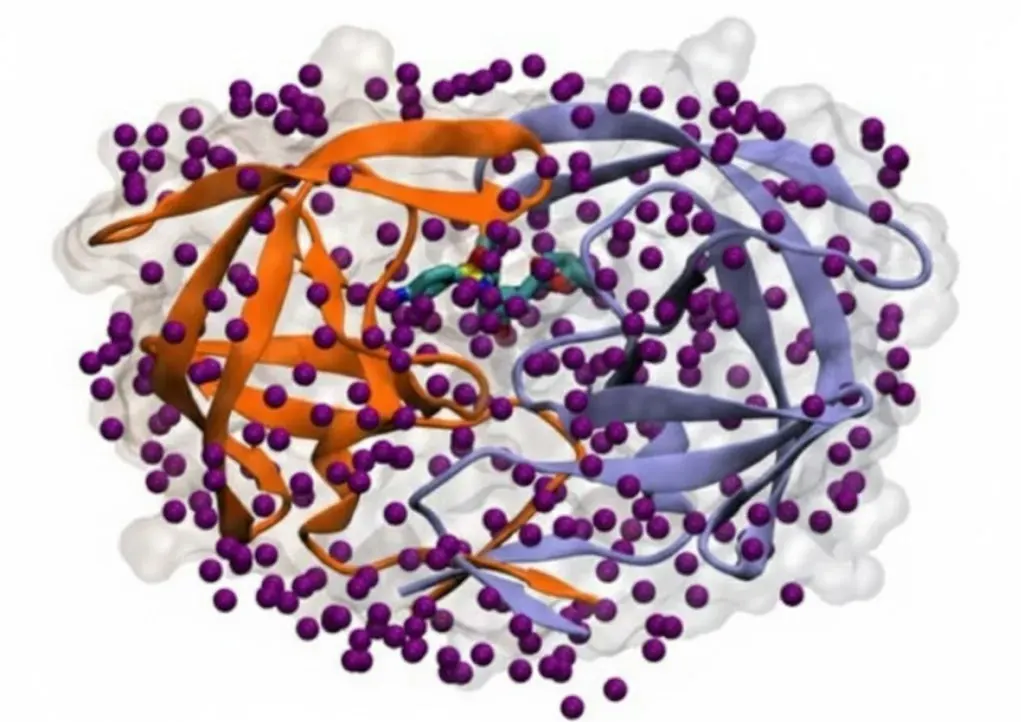

Proteins Live in a Watery World

Inside every cell, proteins exist in a watery soup. But this is no ordinary soup, it’s one where each water molecule has a job to do. Some waters move around freely like audience members milling about, while others are fixed in place like security guards near the stage. These fixed ones are vital, they keep the protein’s shape intact, help residues stay where they should, and maintain that delicate 3D fold that makes everything work. Without water, proteins wouldn’t just act up they’d lose their shape completely and collapse into a floppy, useless structure.

Some water molecules inside a protein are permanent residents, not just passing guests. These are called structural waters, and they act like tiny screws and bolts that keep everything together. They help amino acids hold their positions and stabilize the protein’s inner architecture. When a ligand binds, some of these water molecules may leave, but others stay behind to keep the structure balanced. It’s a bit like rearranging your room, you move a few things, but the walls better stay in place, or the whole setup collapses.

The Water Bridge Effect

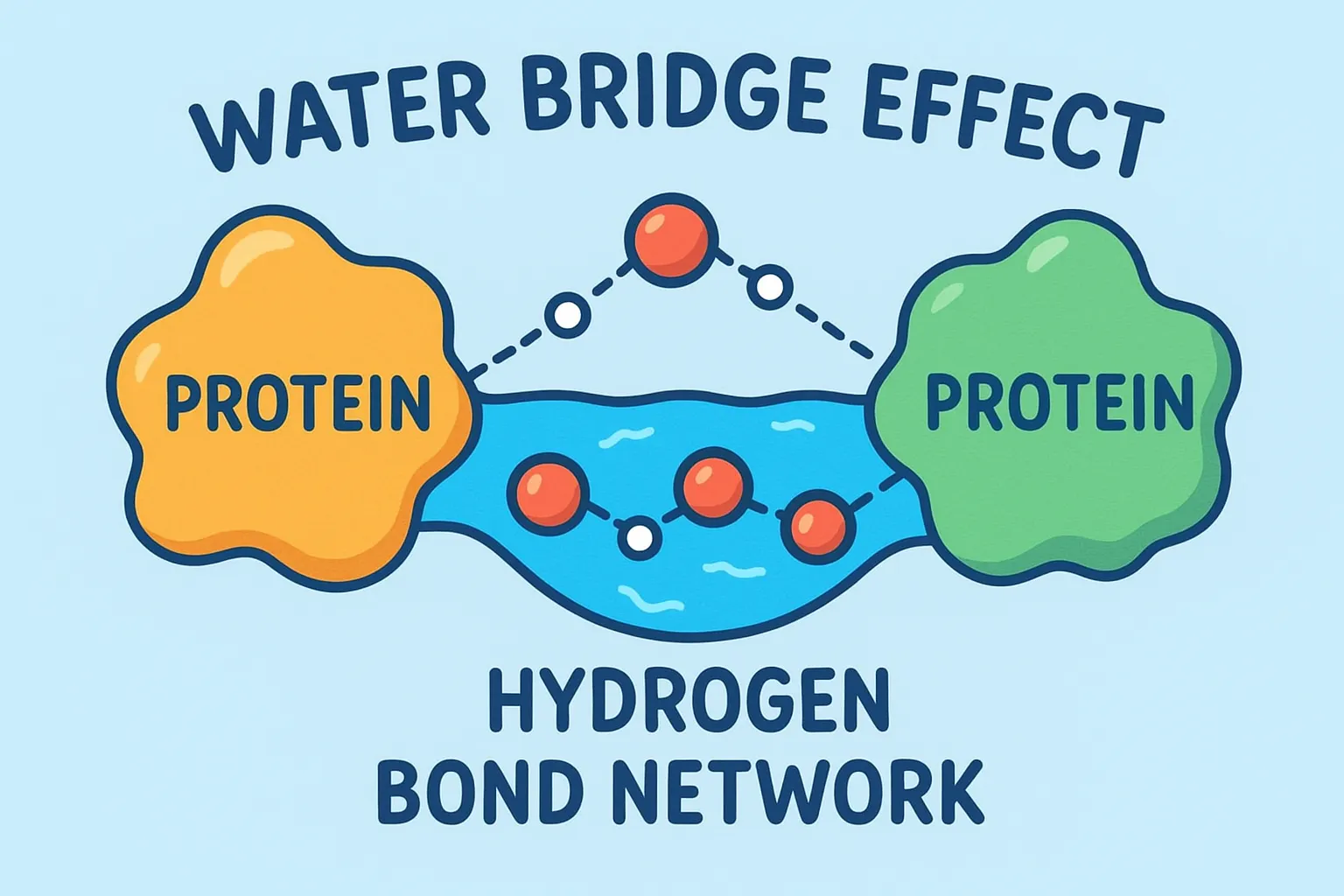

Here’s where water gets creative. Not every amino acid residue can directly connect to the ligand, sometimes the geometry just doesn’t work out. That’s where bridging waters come into play. These molecules form hydrogen bond networks between the ligand and nearby residues, acting like microscopic matchmakers. Instead of forcing a direct link, water steps in, holds both hands, and says, “Relax, I got this.”

This bridging effect adds flexibility and makes the complex more resistant to breaking apart. Even if one bond weakens, the water bridge can help maintain the communication between protein and ligand. Think of it as adding an extra Wi-Fi repeater, the signal stays strong even if the distance increases.

A single water bridge can sometimes stabilize a structure that would otherwise fall apart, especially when the ligand is bulky or irregular. In some enzyme systems, these bridging waters are so important that removing them ruins the entire binding process.

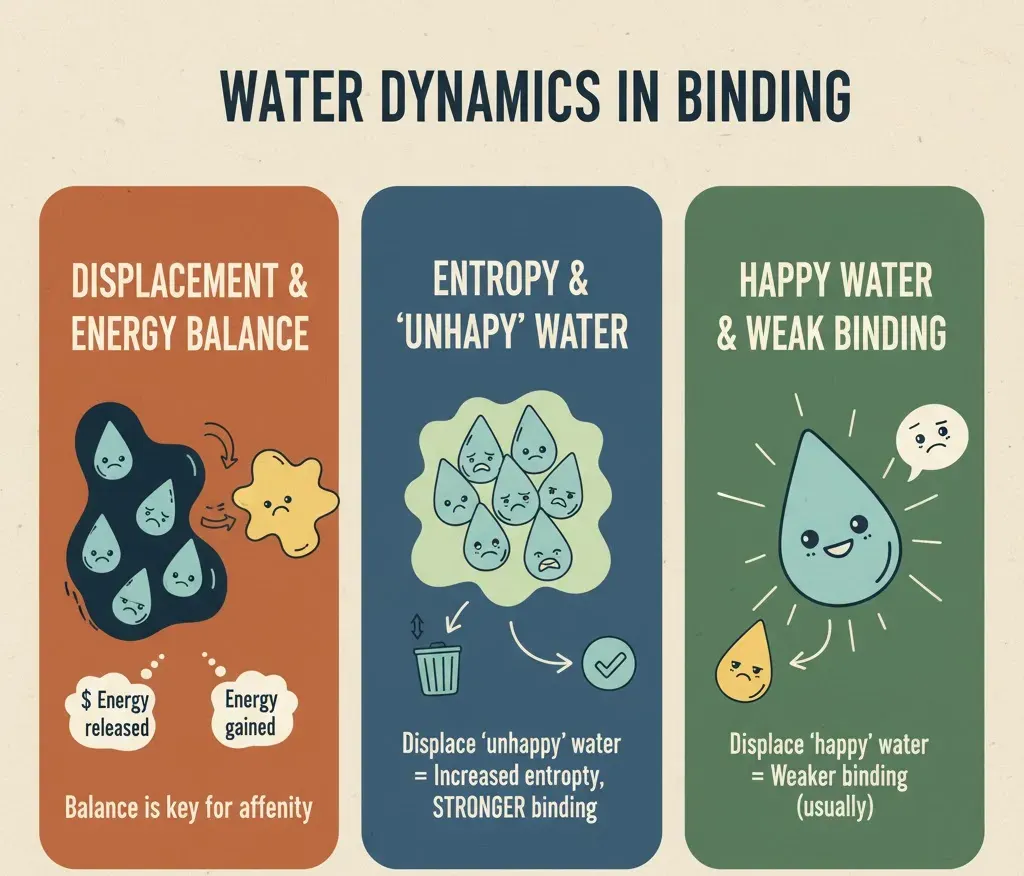

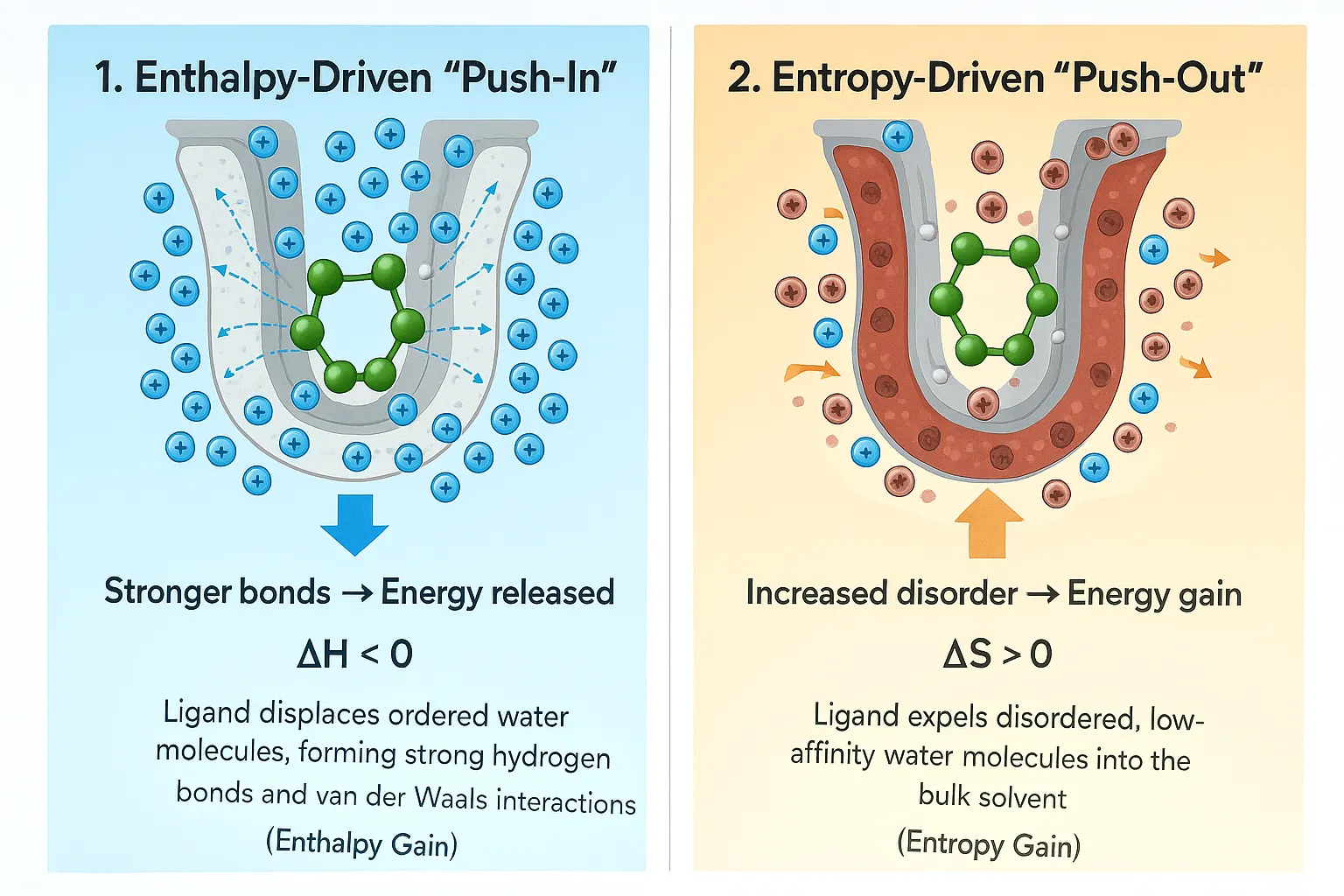

Water and Binding Energy: The Balancing Game

When a ligand binds to a protein, some water molecules are displaced. At first glance, it might seem that removing water always strengthens binding, but the reality is more nuanced. The energy released by displacing water must balance the energy gained from the new protein-ligand interactions. Structural studies, especially crystallography, often show water molecules conserved across multiple protein structures, highlighting their crucial roles in stability and function. Binding itself is governed by the binding free energy (ΔG = ΔH − TΔS), where ΔH represents the enthalpic contribution (energy change) and TΔS represents the entropic contribution (disorder). Removing highly organized, “unhappy” water molecules those that are energetically constrained can increase entropy and lower ΔG, thereby favoring binding. Conversely, displacing “happy,” well-connected water molecules can weaken binding if the ligand cannot compensate with stronger direct interactions or new hydrogen bonds. In the realm of molecular docking and simulation studies, water can literally make or break the binding energy, acting as either a stabilizing ally or a destabilizing obstacle.

When a water molecule forms favorable hydrogen bonds, it strengthens the interaction, but if it is trapped in an energetically unfavorable position, it can weaken binding instead. This delicate balance is reminiscent of arranging a team: having the right players in the right positions makes all the difference. Hydrophobic (water-repelling) and hydrophilic (water-loving) interactions must also stay balanced. When a ligand enters a binding pocket, hydrophobic regions tend to push water away, while hydrophilic regions attract it in. This tug-of-war between forces helps determine the final binding affinity, a measure of how tightly a ligand binds to the protein. Interestingly, many computational studies have shown that explicitly including a few key water molecules gives much more accurate results than removing them entirely. So, when modeling protein–ligand systems, it’s wise not to discard all water molecules; some of them serve as the MVPs of stability, influencing both the energy landscape and the geometry of binding.

| Action | Energy Effect (ΔG = ΔH − TΔS) | Impact on Binding Strength | Drug Design Strategy |

| Pushing out Unhappy Water | Large increase in Disorder (+TΔS). Energy cost (ΔH) is paid off. | Significant Strength Increase | Design the drug to take the exact spot of highly organized, unstable water. |

| Keeping Water (Bridging) | Favorable drop in Energy (-ΔH) due to strong connections. Disorder (TΔS) is penalized (water is stuck) . | Enhanced Precision and Stability | Design the drug to use the structured water molecule as a connecting point (Retention Strategy). |

| Pushing out Happy Water | Small change in Disorder (low gain). Energy cost (ΔH) may be unfavorable. | Strength Penalty (Weaker Binding) | Avoid pushing out water that is highly stable and well-connected, unless the drug forms a much stronger direct connection. |

Table.1 Summary of thermodynamic effects of water displacement on ligand binding and drug design strategies.

Water molecules are dynamic participants in the binding site. They often slip in and out, forming temporary hydrogen bonds and adapting to the protein’s subtle movements. This process resembles a well-choreographed dance, where water moves in rhythm with the protein’s flexing structure, stabilizing newly formed conformations. Some water molecules are so consistently present that they are treated as semi-permanent structural components, while others act like fleeting extras, appearing briefly but performing critical roles in folding, orientation, and proper ligand positioning. Beyond structural stabilization, water helps proteins recover from slight unfolding or shape fluctuations. By cushioning the interior, it allows atoms to “breathe” naturally rather than sticking unnaturally, preventing local collapse and maintaining the overall protein architecture.

Moreover, water can actively participate in chemical reactions. In enzymes, individual water molecules may act as reactants, breaking chemical bonds or assisting in proton transfer, while in receptor-ligand interactions, water can guide the ligand into its proper orientation before binding occurs. Classic examples include HIV protease and carbonic anhydrase, where well-positioned water molecules are critical for both structural integrity and enzymatic function. Removing these waters can dramatically reduce efficiency and alter the protein’s behavior. In essence, water is not merely a passive background solvent in the biochemical theater; it is an active member of the cast, influencing binding energies, reaction pathways, folding dynamics, and the delicate choreography of molecular interactions. By understanding the subtle roles of water, researchers can gain deeper insights into protein-ligand recognition, drug design, and enzymatic mechanisms, appreciating that each water molecule whether fleeting or permanent can be essential to the molecular story.

Water's Outer Ring and Binding Speed

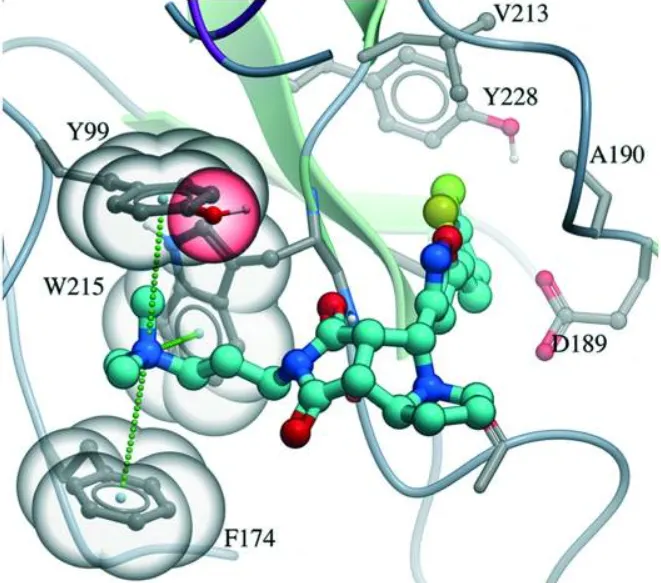

Water's influence is not limited to just the surface where the protein and drug touch (the first hydration shell). Research increasingly confirms that the second ring of water molecules can also be critical for how strongly a drug binds. For computer simulations (like MM/PBSA) to accurately predict binding, they must fully consider the effects of this second ring of water to match experimental data reliably. Moreover, water affects not only the final binding energy ΔG but also how fast the drug attaches (kinetics). The necessary rearrangement of the water network during binding is a crucial step that affects the energy barrier of the reaction. Detailed modeling that included corrections for water free energy helped researchers understand why the drug xk263 binds 1,000 times faster to HIV-1 protease (HIVp) than the drug ritonavir. This shows that the structure of the water around the binding site greatly influences the speed of binding, making water essential for both strong and fast drugs.

Structural Synergy: Water-Mediated Bridges

Water bridges act as flexible connectors when direct protein-ligand bonds aren’t feasible. Research shows that over 85% of protein-ligand complexes in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) contain one or more bridging waters, averaging 3–4 per complex. These waters stabilize complexes, enhance binding precision, and sometimes dictate target specificity.

Real-World Examples

The stabilizing power of water bridges is well-known in many drug targets:

- CDK2 Inhibitors: Studies on CDK2 complexes show that a water-mediated hydrogen bond between the drug and the backbone of residue Glu81 is critical for holding the drug in place . Statistical surveys show that water-connected hydrogen bonds involving an oxygen atom on the drug are about twice as common as those involving a nitrogen atom.

- Thrombin Inhibitors: In one striking example, adding a simple hydrogen-donating ammonium group to a potent thrombin inhibitor led to a massive increase in binding strength (over 500-fold) . X-ray analysis showed this huge boost was because the ammonium group formed a charge-assisted hydrogen bond with the protein and surrounding water, proving how kept water can amplify favorable charge interactions .

These examples confirm that water bridges are not just random parts of the structure, but essential pieces that dictate the precise fit and strength needed for a drug to bind strongly.

| Target System | Water's Role in Complex | Key Structural/Energy Finding |

| Factor Xa (FXa) Inhibitor | Pushing out highly structured water. | Removing thermodynamically costly water significantly increased binding strength (ΔG = -1.92 kcal/mol) |

| CDK2 Inhibitors | Water-connected hydrogen bonds (N-H···O). | Water acts as a bridge between the drug and key protein residues (like Glu81 backbone), locking the drug's shape |

| Thrombin Inhibitors | Charge-assisted water bridge. | Adding an ammonium group led to a >500-fold strength increase via water-mediated, charge-assisted connections . |

| Bosutinib/Kinase Targets | Using a fixed water network. | The drug recognizes its target by engaging a pair of conserved water molecules; the protein's "gatekeeper" residue controls access to them. |

| HIV-1 Protease | Strongly fixed water molecule. | The calculation must account for the large energy cost of keeping this water molecule highly organized . |

Table.2 Examples of how water molecules influence ligand binding across different drug target systems.

Hydration Hot Spots: Mapping Critical Water Sites

Hydration hot spots are tiny regions within protein binding pockets where water molecules have an outsized impact on binding energy. Mapping these spots helps chemists make smart choices: should a water molecule be pushed out to increase disorder (and potentially strengthen binding), or kept to maintain structural stability?

Understanding hydration hot spots gives drug designers two main strategies:

- The Push-Out Strategy: This involves carefully designing a part of the drug molecule to sit exactly where an unstable, highly organized water molecule is located. pushing out these highly restricted molecules leads to a substantial gain in disorder (entropy), which lowers ΔG and makes the drug bind stronger. Drugs designed to expel this high-density, unhappy water have been shown to provide the greatest increase in binding strength.

- The Keep Strategy: If a hot spot corresponds to a water molecule that is very strongly connected and contributes favorably to the system's energy (e.g., highly structured water that forms multiple hydrogen bonds), the best approach is to design the drug to keep this organized water molecule and use it as part of the overall connection network. This captures the structural stability provided by the water bridge.

Water molecules in binding pockets aren’t always happy campers. The inner layer of water is often more crowded than the surrounding solvent, creating a physical barrier that any incoming drug must overcome. When a ligand binds, it may displace some of these waters. While it might seem that removing water always strengthens binding, the reality is subtler. Some waters contribute essential hydrogen bonds, and kicking them out can reduce stability.

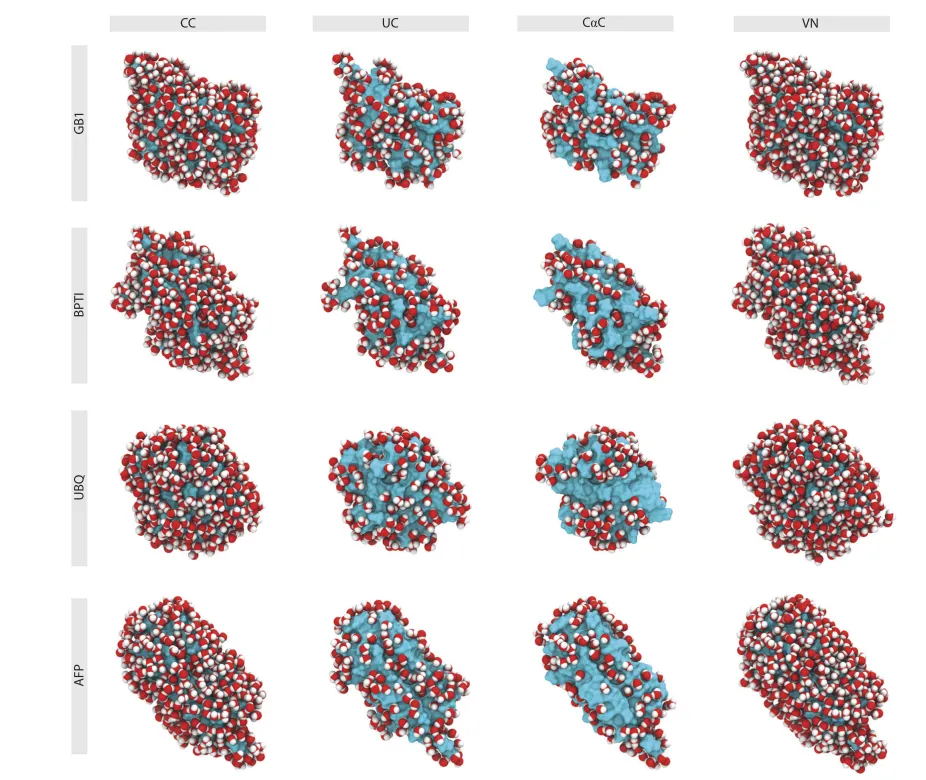

Advanced docking algorithms now often predict which waters are “happy” to leave and which prefer to stay. Crystallography frequently shows structural waters tucked neatly inside binding pockets their repeated presence across multiple protein structures underscores their importance. MD and Monte Carlo simulations reveal how water dynamically rearranges during binding, forming temporary bridges, stabilizing charged regions, and adjusting networks to accommodate the ligand. Some of these key waters are so predictable that modern drug-design software includes them automatically during virtual screening. Ignoring them can lead to false predictions or missed opportunities for effective binding.

Crowded Water at the Binding Site

The physical nature of the water shell places specific limits on drug binding. Looking closely at the protein-water surface shows that water molecules in the inner layer, even near nonpolar parts, are, on average, more crowded than water in the main solvent body. This crowding, which is about 6% denser for globular proteins, means that putting a drug into the binding site requires overcoming a significant barrier related to the water molecules being physically squeezed. This squeezing challenge contributes directly to the energy penalty during computational calculations. Therefore, to get the maximum benefit from pushing out organized water, designers must create drugs that minimize the necessary squeezing penalty while achieving the largest possible gain in disorder.

The Computational Challenge: Modeling Water Accurately

The Limits of Simple Models

Historically, computer-aided drug design used quick, simple scoring methods, often relying on implicit solvent models (simple water models). These models are fast but cannot accurately capture the specific, local effects of individual, organized water molecules or properly account for the subtle disorder changes that define the hot spots. Because these simple models fail to capture the molecular detail of the water environment, the estimated binding energies are often inaccurate.

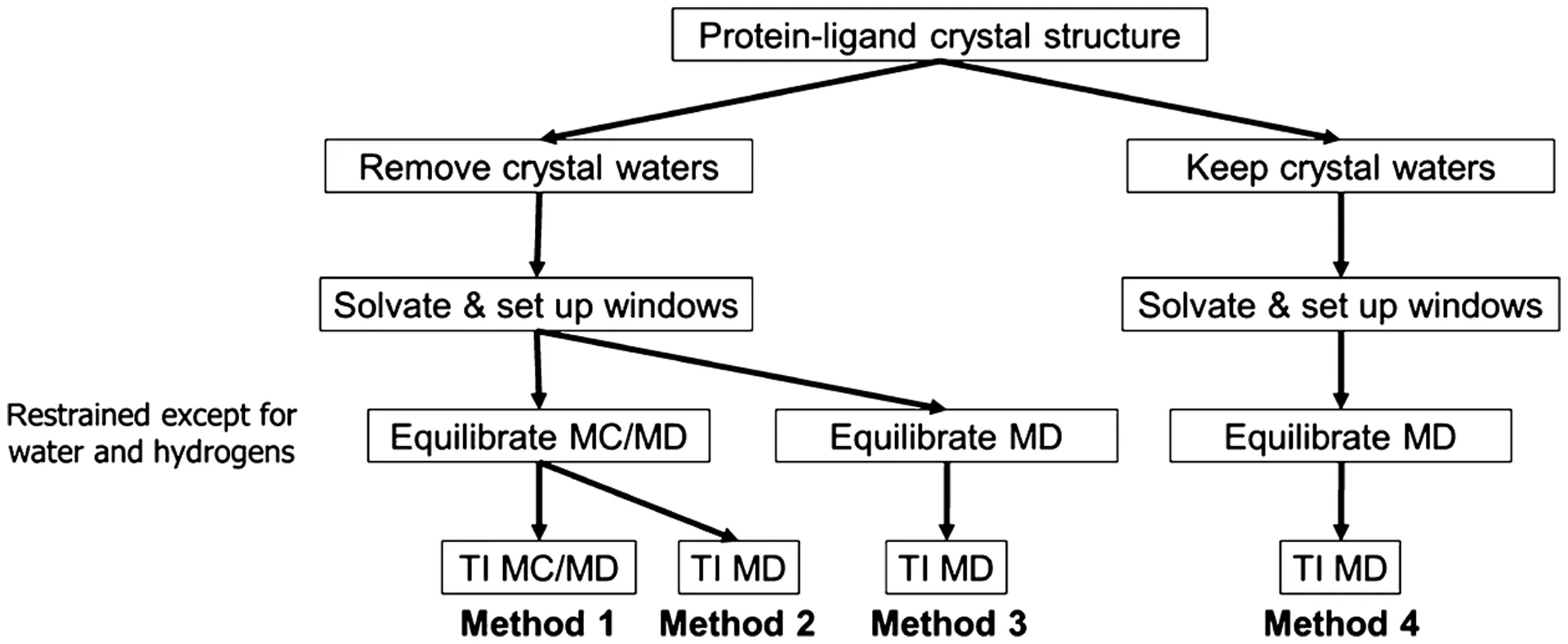

The Problem of Slow Water Movement and Hybrid Solutions

While detailed MD simulations are necessary, they have a major limitation: slow water movement. When parts of the binding site are deeply buried or hard for the main solvent to reach, the time needed for water molecules to move in or out to reach a stable balance (equilibration) can be much longer than the time the simulation can practically run. This slow sampling of water movement is particularly problematic when calculating binding energies. For example, if a drug is modified to be smaller, the pocket might accommodate an extra water molecule. If the simulation doesn't run long enough to see that water move in, the calculated energy will be wrong. To fix this, hybrid Monte Carlo/Molecular Dynamics (MC/MD) methods have been developed . MC/MD speeds up the process of water reaching balance between the bulk solvent and buried pockets by including random moves (Monte Carlo) that allow water to easily enter or leave confined spots in a way that is still thermodynamically correct . Using MC/MD dramatically improves the accuracy of calculated results and reduces the difference between calculating the change forward and backward, confirming that getting the water balance right is essential for accurately calculating the final binding energy (ΔG).

Sensitivity to Water Models

The specific explicit water model chosen (like TIP3P or TIP5P) is another critical factor affecting the accuracy of calculated energies. Different popular models show variations in physical properties, such as the calculated water density and how much steric squeezing occurs. For instance, the steric compression penalty, measured by the van der Waals decoupling free energy, was found to be noticeably higher for TIP3P and TIP4P models compared to TIP5P. Furthermore, simulations of complexes, like the CD44–HA complex, showed that the TIP5P water model gave the lowest structural difference (RMSD) from the experimental starting structure compared to other models . This variation means the choice of water model is important it is a source of thermodynamic uncertainty and requires researchers to choose models that accurately reflect the known physical properties of the solvent .

Moving forward from here

The strong evidence showing water's dual role as both a driver of disorder (entropy) through the strategic removal of unhappy molecules and as an energy stabilizer (enthalpy) through water-mediated connections makes its complete inclusion mandatory for modern drug development . Overcoming the technical difficulties in accurately modeling this complex system is quickly turning water from a frustrating variable into a powerful tool for fine-tuning how drugs interact with their targets. Computer methods continue to advance to include water more explicitly and intelligently. Recent approaches, such as GraphWater-Net, use network structures to map protein atoms, drug atoms, and the complex network of water molecules and their interactions . By using these networks to extract interaction details, this model significantly improves the prediction of drug-protein binding strength, outperforming previous advanced methods by a margin of 0.022 to 0.129 in correlation . To be truly successful, therapeutic development needs to fully consider water effects not just in the final binding strength (ΔG), but also in the speed of binding (kinetics). As computing power increases and hybrid simulation techniques become standard, researchers are gaining a clearer atomic-level view of the water environment. This allows for the smart design of drugs that maximize the thermodynamic benefits of water rearrangement while minimizing physical and entropic costs. This complete approach ensures that water, the most abundant molecule in biological systems, is finally recognized and utilized as a decisive partner in molecular recognition.

Conclusion

For drug developers, water is both a friend and a challenge. If you include too much of it in a model, the system gets noisy and slow. If you ignore it, your predictions may go completely off track.

A well-designed ligand often fits into a binding site in a way that either makes smart use of bridging waters or replaces them efficiently. Some drugs even depend on water bridges for optimal binding.

Pharmaceutical chemists now pay close attention to these “hydration sites” specific points where water molecules consistently help in maintaining stability. Understanding which waters to keep and which to replace can make the difference between a weak binder and a powerful therapeutic.

You could say that water is the silent support staff that keeps the stars the protein and the ligand looking good on stage. Without it, the structure falls flat, and the whole biochemical show loses balance.

So the next time you see a molecular model and think, “Those water molecules are just background,” remember some of them might be the real heroes holding the story together.

References

- Michel, J., Tirado-Rives, J., & Jorgensen, W. L. (2009). Prediction of the water content in protein binding sites. Chemical Reviews, 109(9), 3509–3529.

- Huggins, D. J., et al. (2011). Role of water in biological recognition. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 54(21), 7105–7123.

- Young, T., Abel, R., Kim, B., Berne, B. J., & Friesner, R. A. (2007). Motifs for molecular recognition exploiting hydrophobic enclosure in protein–ligand binding. PNAS, 104(3), 808–813.

- Ball, P. (2008). Water as an active constituent in cell biology. Chemical Reviews, 108(1), 74–108.

- Ross, G. A., Bodnarchuk, M. S., & Essex, J. W. (2015). Water sites, networks, and free energies with grand canonical Monte Carlo. JACS, 137(47), 14930–14943.

- Aldeghi, M., Bluck, J. P., & Biggin, P. C. (2022). Computational mapping of hydration sites in proteins. WIREs Computational Molecular Science, 12(1), e1525.

- Abel, R., Young, T., Farid, R., Berne, B. J., & Friesner, R. A. (2008). Role of the active-site solvent in the thermodynamics of factor Xa ligand binding. Chemical Reviews, 108(9), 3716–3756.

- Poornima, C. S., & Dean, P. M. (1995). Hydration in drug design. 1. Multiple hydrogen-bonding features of water molecules in mediating protein–ligand interactions. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design, 9(6), 500–512.

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.