Generative models in designing novel scaffolds

Drug discovery in past was like hunting for a rare spice in an endless pantry. Scientists would sift through mountains of existing molecules a “virtual screening” of billions of compounds hoping that one might bind to a disease target. This process has often been compared to finding a needle in a haystack. But what if, instead of rummaging through that pantry, we could magically cook up brand-new molecular recipes on demand? Thanks to advances in AI, that fantasy is becoming reality. Modern generative models allow researchers to design molecules from scratch, a shift from selection to creation in drug discovery.

In practical terms, the old approach meant testing large libraries of known molecules (or docking them computationally) to see which ones might work. For example, traditional highthroughput screening might evaluate billions of compounds to find a handful of leads, at enormous cost and time. In contrast, virtual generation uses neural networks to propose entirely new compounds that have never been synthesized before. Instead of only picking from pre-made parts, AI lets us imagine and build novel “lego blocks” of chemistry that fit our target. This new paradigm aims to explore chemical space far beyond what any existing database holds. In fact, recent reports show generative models discovering molecules with better predicted binding and drug-like properties than any hit found by a brute force screen. In one case, an AI called IDOLpro used guided diffusion models to create ligands with 10–20% higher binding scores than the best hits from an exhaustive virtual screen, while also improving synthetic accessibility. And it can even include ADME/Tox (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) predictors in its scoring, optimizing multiple constraints at once. These successes hint at a future where virtual generation yields rich leads faster and smarter than ever.

Generative Models: VAEs, GANs and Transformers

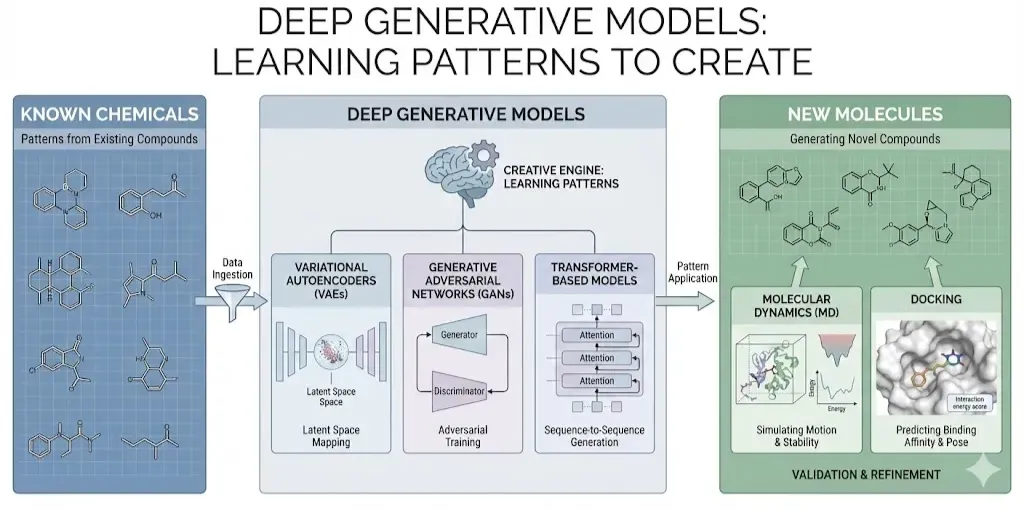

How do these AI wizards actually conjure new molecules? At the heart of virtual generation are deep generative models. Three popular classes are Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Transformer based models. Each has a different “creative engine,” but all share the goal of learning patterns from known chemicals and using them to make new ones.

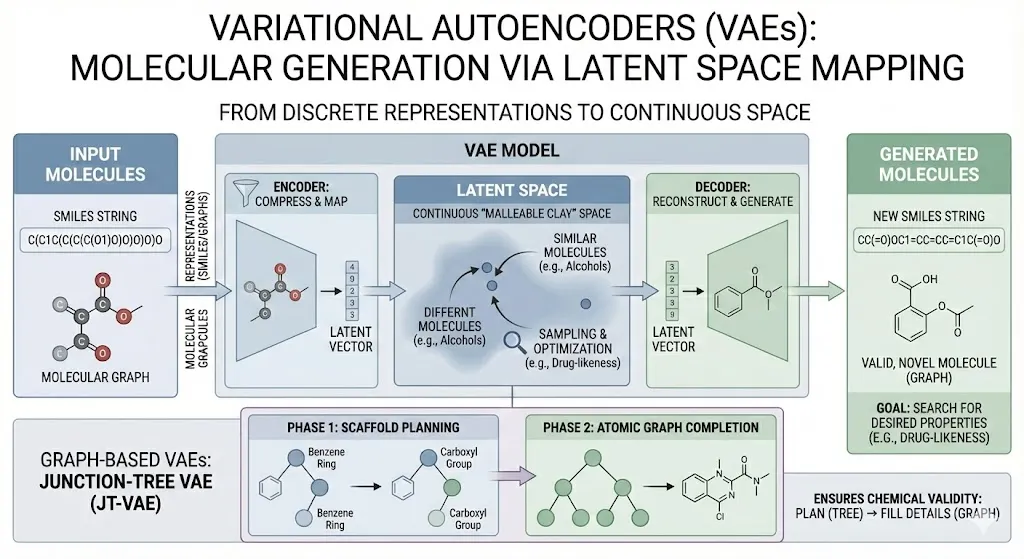

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

A VAE learns to compress and then reconstruct molecules. In practice, a molecule is often represented as a SMILES string (a text notation of its structure) or as a graph of atoms and bonds. The VAE has two parts: an encoder that turns the input (SMILES or graph) into a point in a continuous “latent” space, and a decoder that tries to map back from that latent vector to a valid molecule. By training on a dataset of existing compounds, the VAE learns a smooth map: similar molecules end up near each other in latent space. Once trained, we can sample or optimize points in this latent space and decode them to generate new SMILES strings. This lets us search for molecules with desired features. For example, Gomez-Bombarelli et al. used a VAE to map discrete SMILES into a low-dimensional continuous space, enabling efficient optimization for properties like drug likeness. In other words, VAEs let us treat molecules somewhat like malleable clay in a continuous space, rather than as isolated strings.

There are also graph-based VAEs. One example is the Junction-Tree VAE (JT-VAE), which generates molecules in two phases(A N M Nafiz Abeer et al., 2024). First it builds a tree of chemical substructures (think functional groups) that outline a scaffold. Then it pieces together the atomic graph according to that tree. The result is often a valid, novel molecule. This two-stage approach helps ensure chemical validity: the model first plans a roughly “legal” structure (the tree of known fragments) and then fills in details.

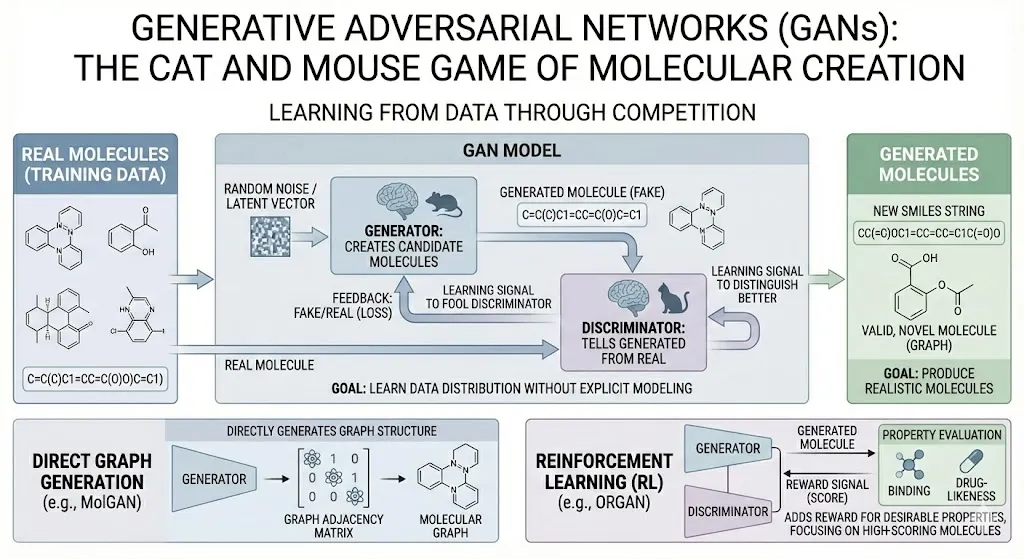

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Think of a GAN as two neural networks playing a game of cat and mouse. One network (the generator) creates candidate molecules, while the other (the discriminator) tries to tell generated molecules apart from real ones it saw in training. Over many rounds, the generator learns to produce molecules that look real enough to fool the discriminator. In effect, GANs learn the distribution of the training data without explicitly modeling it. For molecules, this can mean generating new SMILES or even molecular graphs. Some models (like MolGAN) directly generate graph adjacency matrices of small molecules. Others incorporate reinforcement learning: they add a reward signal for desirable properties. For instance, the ORGAN model is a GAN-like framework where molecules scoring well (e.g. good binding or drug-likeness) give higher reward. This reward is incorporated into the training so that the generator gradually focuses on producing high-scoring molecules(Abeer et al., 2024). In short, GANs are another way to learn to write new SMILES strings (or build graphs) by competing against a critic.

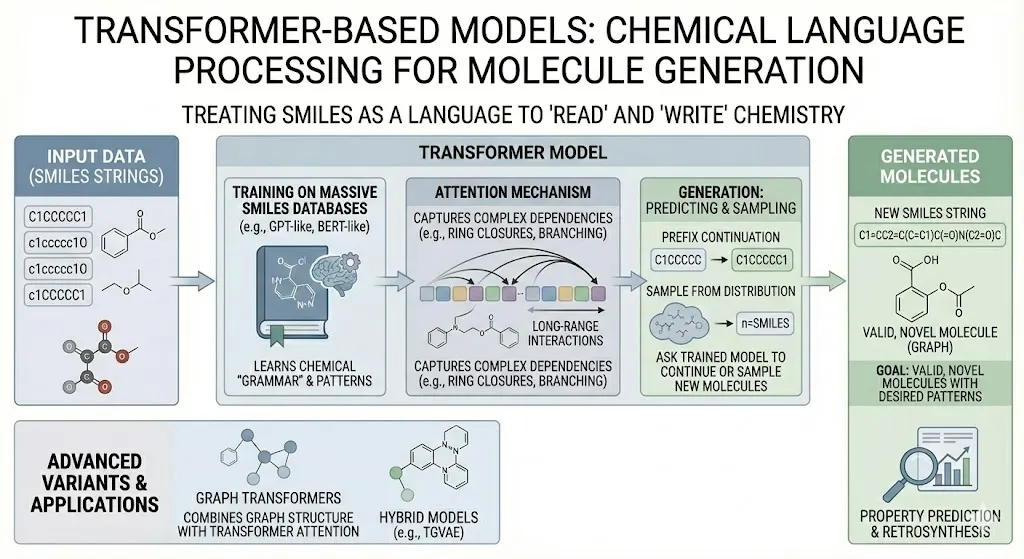

Transformer-Based Models

The recent NLP revolution with Transformers has spilled into chemistry. Here, SMILES strings are treated literally as a chemical language. A Transformer model (like a molecule-version of GPT or BERT) is trained on massive databases of SMILES. By learning the “grammar” of chemistry, it can then predict missing parts of a string or generate entire new strings. Since Transformers attend to all parts of the sequence, they can capture complex dependencies (like ring closures, branching) in SMILES. One can simply ask a trained “SMILES-GPT” to continue a prefix or sample new molecules from its learned distribution. Researchers have indeed built “chemical language models” that generate valid, novel SMILES with desired patterns (Bran & Schwaller, 2023). The power of this approach is that any improvement in language modeling (like the GPT-4 scale models) could translate into better molecule generation. Transformers have already been used for retrosynthesis, property prediction, and now generation all by exploiting analogies between chemical and natural language. In short, these models read and write chemistry in the language of SMILES. (Advanced variants even treat molecules as graphs with attention mechanisms or use hybrid graph-transformer models like the TGVAE, but at core it’s “make SMILES with language AI.”)

| Model | Input format | Key components | Training Objective | Strengths | Challenges |

| Variational Autoencoder | SMILES / Graph | Encoder, Decoder, Latent Space | Reconstruct input while regularizing latent space | Smooth latent space, useful for optimization and interpolation | May generate invalid molecules, hard to control output distribution |

| Generative Adversarial Network | SMILES / Graph | Generator, Discriminator | Fool the discriminator | High-quality outputs, captures complex data distributions | Training instability, mode collapse |

| Transformer-based | SMILES | Attention Layers, Token Embeddings | Learn contextual representations to predict next tokens | Handles long-range dependencies, scalable with large datasets | Requires large datasets, computationally intensive |

Table: Comparison Between various models discussed previously

Each of these generative approaches has its strengths. VAEs provide a smooth latent space useful for interpolation and systematic exploration of novel scaffolds. GANs focus on generating realistic examples and can achieve sharp, detailed designs (though at the risk of reduced diversity or mode collapse). Transformers, meanwhile, excel at learning complex sequential or graph patterns and can scale with data (especially when leveraging large pretrained models). In practice, one might compare them by metrics like validity (percentage of chemically valid molecules generated), uniqueness (how many outputs are distinct), and novelty (how different they are from training data), or by downstream performance after property optimization.

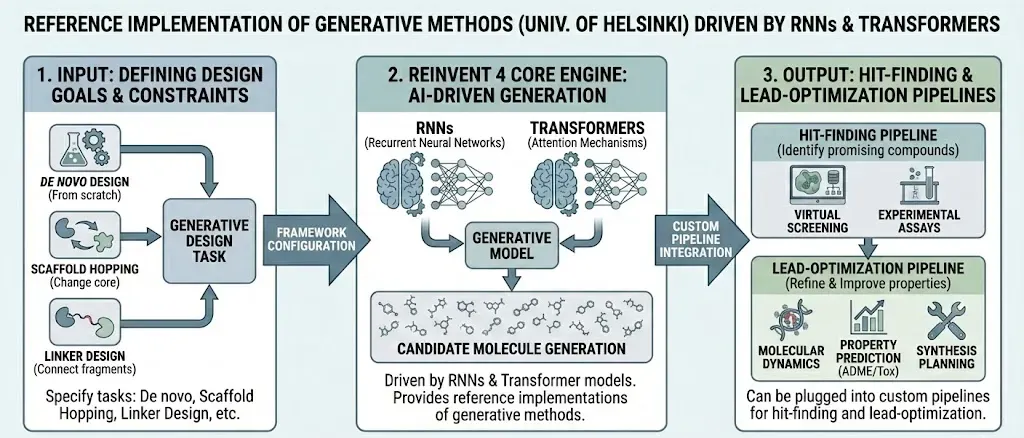

Notably, many real world tools use combinations of these methods. For example, the open-source REINVENT 4 framework uses recurrent neural networks and Transformers to drive molecular generation, wrapped in reinforcement learning loops (Loeffler et al., 2024). It can propose R-group substitutions, design libraries, or hop scaffolds, all through generative AI

Balancing Act: Multi-Objective Molecular Design

Designing a molecule isn’t just about making it bind tightly to the target. A good candidate must also be realizable and drug like. This means it should be synthesizable in the lab, and have acceptable ADMET properties (like solubility and low toxicity). Thankfully, modern generative models are getting better at juggling multiple criteria at once.

The key is multi-objective optimization. In practice, this means the AI isn’t just aiming for one score, but balancing several. For instance, some approaches build a single “score” that combines binding affinity prediction, synthetic accessibility, and drug-likeness. Others use Pareto-front ideas or guided retraining to emphasize trade offs. A recent example is the IDOLpro model (from the Chemical Science group). It uses a diffusion based generator whose latent variables are steered by differentiable scoring functions for multiple targets. In tests, IDOLpro created molecules with 10–20% higher predicted binding affinities than the best competing generative method, while also improving synthetic accessibility. In other words, it found molecules that not only fit the target pocket tightly but were also easier to make. The model even beat an exhaustive virtual screen: none of the molecules in the huge database had both the high binding and good synthesis scores that IDOLpro’s generated compounds did. List of some of the typical constraints that these AI models consider:

- Target Affinity: Models often include a docking or physics-based score (like AutoDock Vina or a ML binding predictor) so that generated molecules should snugly fit the protein pocket.

- Synthetic Accessibility: Neural networks can incorporate scores that estimate how hard it is to synthesize the molecule (e.g. SA score or retrosynthesis-derived metrics). Generators are then biased toward structures with higher feasibility.

- ADMET Properties: Predictors for absorption, solubility, metabolic stability, toxicity, etc., can be used as additional scoring functions. By optimizing for these, the model avoids crazy chemical features that would make a drug impossible.

By tweaking the training or the scoring during generation, AI can propose molecules that hit all these checkpoints. For example, some tools let you “plug in” any differentiable function (including ADME/Tox predictors) as an optimization target(Kadan et al., 2025).

The end result is a kind of controlled creativity: the model is no longer just freewheeling random chemist, but a chemist with a rulebook. This ability to satisfy multiple constraints is what makes generative design so exciting to pharma: one can, in principle, design a compound that not only binds its target strongly but also already looks like a viable drug candidate in terms of chemistry and safety.

Diffusion Models: A New Direction for Pocket-Aware Molecule Generation

While VAEs, GANs, and Transformers have pushed molecular generation forward, diffusion models are quickly becoming serious contenders, especially for structure-based drug design. Inspired by image generation tools like DALL·E and Stable Diffusion, these models work in reverse: they start with random noise and slowly “denoise” it to form meaningful outputs. In chemistry, that output can be a valid, 3D molecular structure.

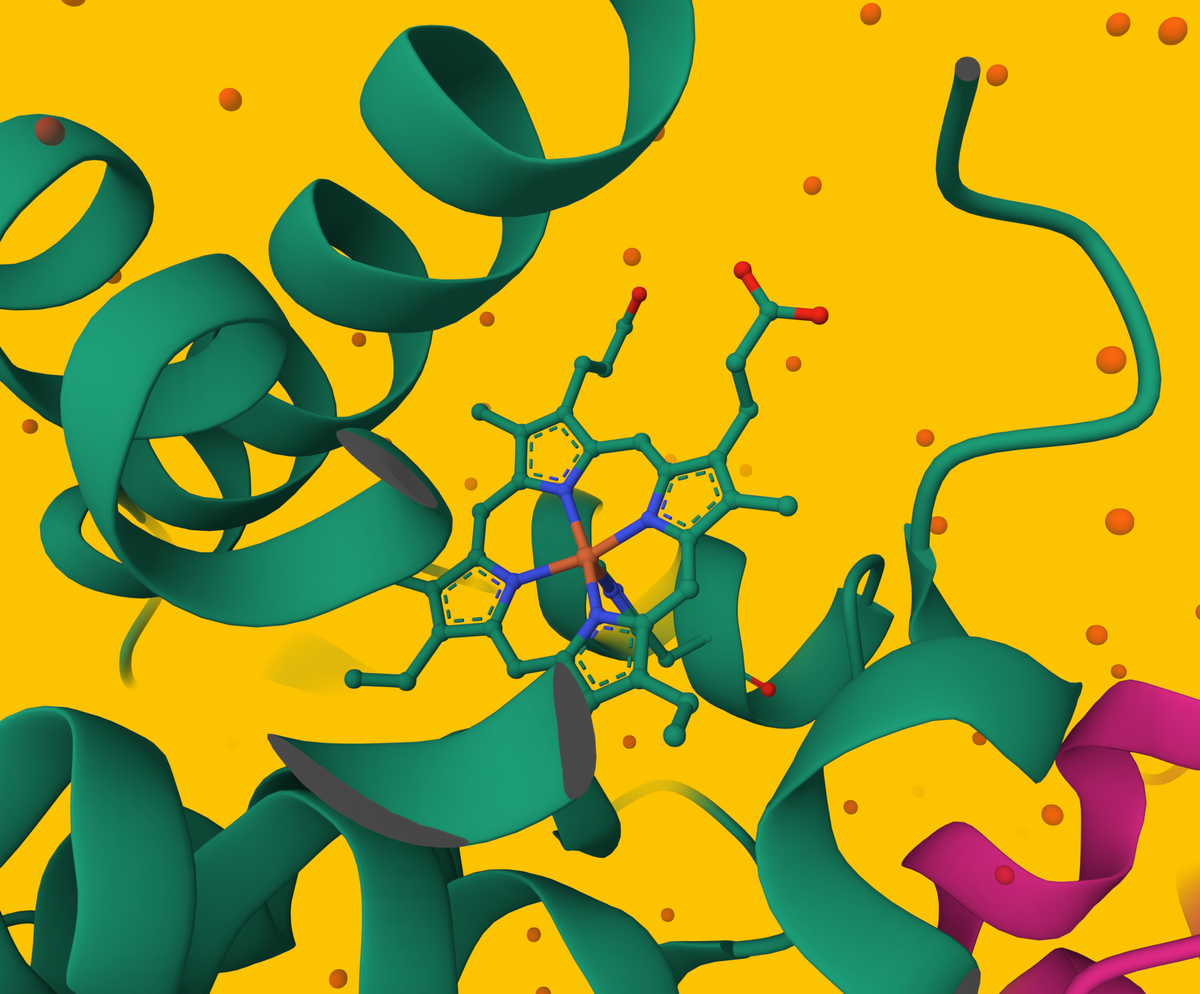

In ligand design, diffusion models are particularly powerful because they can build molecules atom-by-atom or fragment-by-fragment inside the 3D context of a protein pocket. That makes them extremely pocket-aware, which is a major advantage over models that generate SMILES strings independently of structural context.

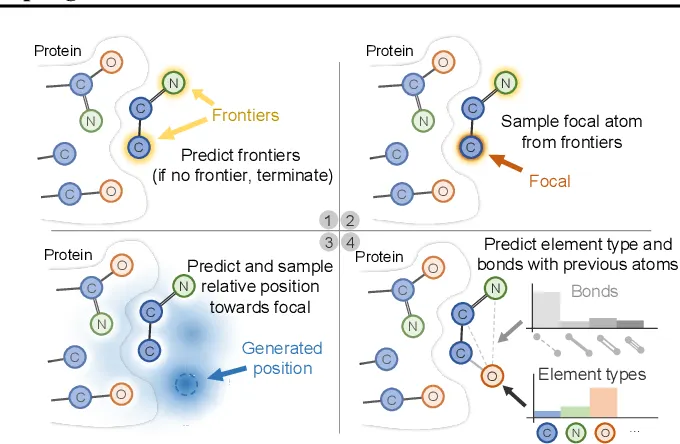

Pocket2Mol is one of the first 3D diffusion based frameworks built for generating ligands directly within a protein binding pocket. It takes as input a 3D representation of the pocket (derived from a protein-ligand complex or structure prediction) and uses a two-stage generation process:

- Molecular topology prediction – the model first generates a graph structure that defines which atoms are connected and how.

- 3D coordinate generation – then it produces the 3D spatial arrangement of the atoms so that the final molecule fits snugly into the pocket.

Pocket2Mol was trained on real protein-ligand complexes from the PDBbind dataset, learning how ligands typically conform to their pockets. A key strength is its ability to produce ligands that are physically plausible right out of the model, requiring less post-generation docking or clean-up. It also tends to propose diverse scaffolds, not just variations on known templates, because it learns directly from structure rather than relying on SMILES data.

Pocket2Mol's innovation is in treating molecular generation as a geometrically conditioned graph construction problem—which is ideal for tasks like fragment growing, scaffold hopping, or structure-based screening when the binding site is known.(Yu et al., 2022)

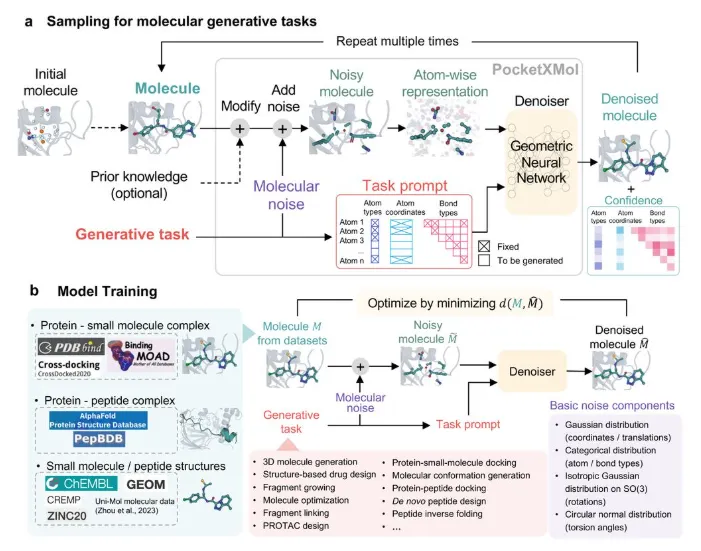

PocketXMol

PocketXMol builds on the idea of pocket-conditioned generation using a more advanced 3D denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM). Where Pocket2Mol uses a two-stage system, PocketXMol operates in a fully unified framework:

- It takes a 3D binding pocket as input (represented as a voxel grid or mesh)

- It incorporates spatial, electrostatic, and residue-type features into its conditioning

- Then, through a denoising diffusion process, it gradually constructs ligand atoms and bonds in 3D space

One of the standout features of PocketXMol is its multi-step ligand optimization—the model doesn’t just generate one shot; it can iteratively refine molecules during generation to improve fit, binding potential, and drug-likeness. It also supports multi-objective optimization natively, factoring in synthetic accessibility and ADMET predictions during generation (Orvieto et al., 2023).

Compared to traditional pipelines, PocketXMol eliminates the need for post-generation docking. Since it builds ligands directly within the 3D pocket during training, its outputs tend to be highly accurate in both shape complementarity and interaction hotspots.

LiteFold unifies all of it for Rapid Ligand Generation

Denovo Drug Design using LiteFold Platform

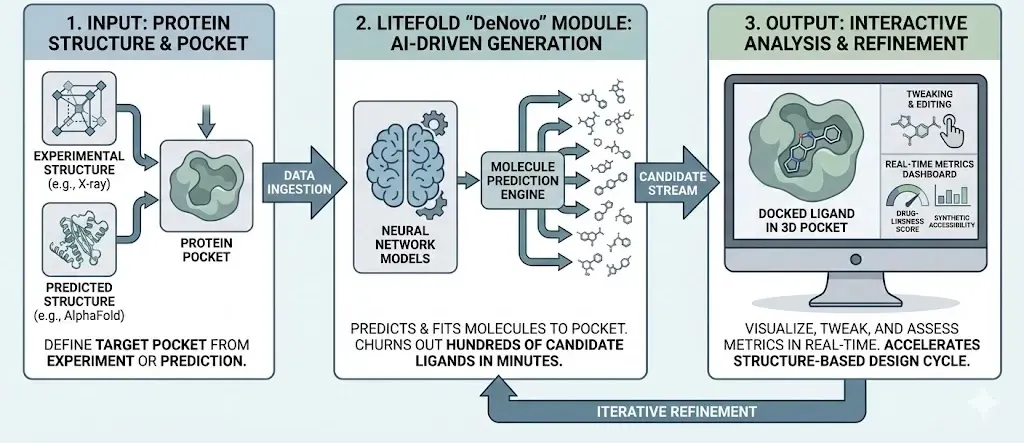

These ideas aren’t just academic. Several tools and platforms are bringing generative design into the hands of chemists and biologists. LiteFold’s “DeNovo” module lets users specify a protein pocket (from experiment or a predicted structure) and then churns out hundreds of candidate ligands in minutes. Under the hood, LiteFold uses diffusion based neural network models to predict molecules that fit the pocket. Users can then visualize each new molecule docked in 3D, tweak them, and see metrics like drug-likeness or synthetic accessibility in real time. In short, LiteFold automates and accelerates the structure-based design cycle.

LiteFold’s design engine tightly couples multiple generative models in one workflow (see the provided system-flow diagram). In practice, the platform first encodes the target protein pocket and then simultaneously leverages diffusion models to propose new ligands

The model learns a continuous latent embedding of molecules (and protein induced conformations) to enable smooth sampling and interpolation of chemical space. In effect it “polices” the diffusion model outputs, nudging generated candidates toward realistic, valid chemistries. In this way the three architectures complement each other. We have explained this in more details in our blogpost here:

Conclusion

The shift from screening to generation is reshaping how we think about drug discovery. Rather than passively searching existing libraries, scientists can now actively explore uncharted chemical terrain. This AI-powered creativity is, in effect, turning the drug lab into a playground of molecules. As with any emerging technology, there are challenges: ensuring generated molecules are truly novel (not just close copies of training data), validating AI predictions experimentally, and integrating human intuition with machine imagination. Yet the progress is undeniable. Modern generative models can already propose hundreds of candidate structures that are both potent and practical.

For pharmaceutical researchers, this means a new toolkit: instead of brute-forcing screens, teams can seed the process with a target structure and ask AI to dream up leads. For scientifically curious readers, it’s an exciting proof that concepts from language and vision (like Transformers and diffusion) are finding home in chemistry. In the coming years, we may see even more synergy. for example, combining generative chemistry models with AI-predicted protein structures or real-time bioassay data. The key message is that AI no longer just reads the periodic table, it’s learning to write it.

In short, drug discovery is becoming more like engineering than guesswork. With VAEs, GANs, and Transformers as our new molecular apprentices, we have the potential to design tailor-made therapies at a scale and speed previously impossible. We’ve gone from scouring the shelves of known compounds to playing in a generative sandbox of possibilities. The future drug is no longer just waiting to be found it can now be imagined, built, and tested by machines (and people) together.

References

A N M Nafiz Abeer, Urban, N. M., Weil, M. R., Alexander, F. J., & Yoon, B.-J. (2024). Multi-objective latent space optimization of generative molecular design models. Patterns, 5(10), 101042–101042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2024.101042

Abeer, A. N. M. N., Urban, N. M., Weil, M. R., Alexander, F. J., & Yoon, B.-J. (2024). Multi-objective latent space optimization of generative molecular design models. Patterns, 5(10), 101042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2024.101042

Bran, A. M., & Schwaller, P. (2023). Transformers and Large Language Models for Chemistry and Drug Discovery. ArXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06083#:~:text=,data%2C like spectra from analytical

Kadan, A., Ryczko, K., Lloyd, E., Roitberg, A., & Yamazaki, T. (2025). Guided multi-objective generative AI to enhance structure-based drug design. Chemical Science, 16(29), 13196–13210. https://doi.org/10.1039/d5sc01778e

Loeffler, H. H., He, J., Alessandro Tibo, Janet, J. P., Alexey Voronov, Mervin, L. H., & Engkvist, O. (2024a). Reinvent 4: Modern AI–driven generative molecule design. Journal of Cheminformatics, 16(1), 20–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-024-00812-5