Ensemble Docking vs Static docking. When Does Protein Flexibility Matter?

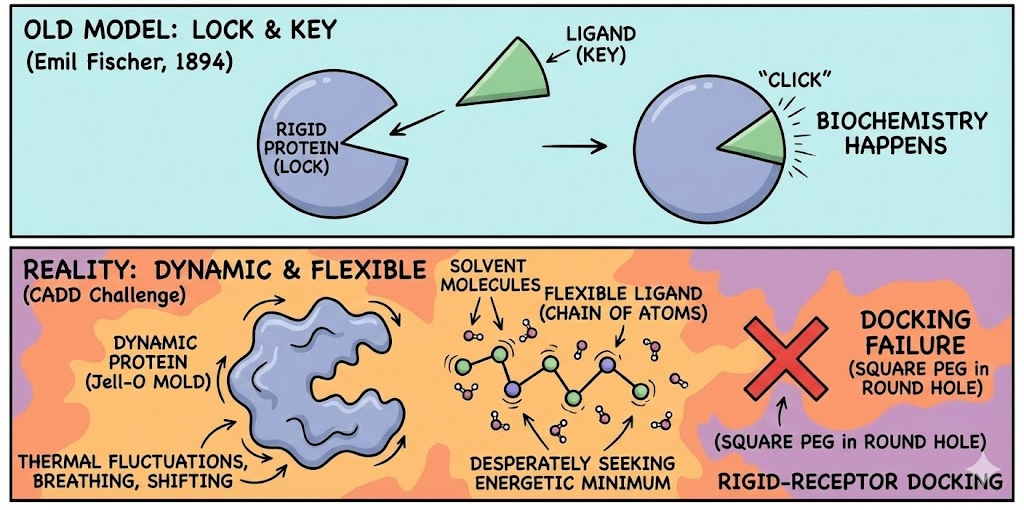

If one were to trust the diagrams found in introductory biology textbooks, molecular recognition would appear to be a serene, orderly, and deterministic affair. The "Lock and Key" model, proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894, depicts the protein as a rigid, Pac-Man-like entity with a mouth the active site gaping open in a fixed, immutable geometry. The ligand, shaped conveniently like a specific wedge of cheese or a geometrically perfect key, floats passively through the cytosol until it slots perfectly into the gap. Click. Biochemistry happens.

This model is elegant. It is intuitive. And, for the doctoral student staring at a docking failure rate of 90% on a Friday evening, it is an absolute fabrication.

The persistence of this analogy has created a "square peg in a round hole" cognitive dissonance in the field of Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD). The reality of the microscopic world is not static; it is a chaotic storm of thermal fluctuations. Proteins are not locks; they are more akin to Jell-O molds vibrating in a washing machine. Ligands are not keys; they are flexible chains of atoms desperately seeking an energetic minimum while being bombarded by solvent molecules. When a researcher attempts to perform rigid-receptor docking forcing a static ligand into a static crystal structure they are essentially trying to park a Cadillac in a garage that is currently breathing, shifting, and occasionally collapsing upon itself.

1. The Cultural Despair of the Docking Community

The psychological toll of this thermodynamic reality is well-documented in the digital confessionals of the scientific community. On forums like Reddit, the frustration manifests in memes and threads titled "Molecular docking struggles," where bioinformaticians vent about the absurdity of their results. Users share the existential dread of obtaining binding affinity scores of +500 kcal/mol because a single side-chain rotamer in the receptor clashed with the ligand, resulting in a physical impossibility that the software scores as "highly unfavorable" rather than "physically impossible".

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.

These cultural artifacts the memes about "forbidden" bond angles and the despair over software errors mask a serious scientific bottleneck. The humor is a coping mechanism for the limitations of the "Lock and Key" paradigm. The inability of static docking to account for protein flexibility results in false negatives: missed drug candidates that could have cured a disease but were rejected because the crystal structure's active site was closed by 1.5 Ångströms at the moment of crystallization.

1.2 The Transition to Rigor

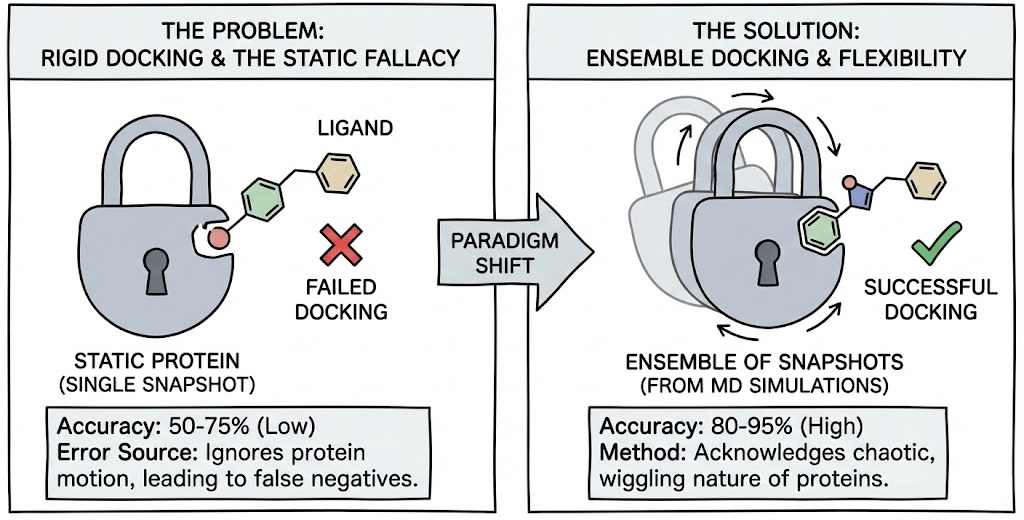

However, the "funny" side of docking failures quickly turns serious when the stakes are human health. The exclusion of protein flexibility is not just a source of frustration; it is the primary source of error in Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD). Rigid docking efforts typically show performance rates between 50% and 75%, while methods that account for flexibility can enhance pose prediction accuracy to 80–95%.

This Blog transitions from the "static fallacy" to the rigorous, high-performance computing solutions that address it. We explore the paradigm shift from static docking to Ensemble Docking, a methodology that acknowledges the chaotic, wiggling nature of proteins. We will dissect the integration of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to generate "snapshots" of protein motion, analyze when this computational expense is justified, and provide exhaustive case studies from the cryptic pockets of IL-2 to the shapeshifting active sites of kinases demonstrating that in the world of molecular docking, flexibility is not just a feature, it is the function.

2. The Physics of Wiggling: Thermodynamics of Molecular Recognition

To understand why ensemble docking is necessary, we must first dismantle the physics of the static model. Proteins are thermodynamic ensembles, not statues. They exist as a population of conformations, navigating a complex energy landscape.

2.1 The Models of Binding

The limitations of the "Lock and Key" model led to two sophisticated successors that inform how we approach flexible docking.

2.1.1 The Induced Fit Model

Proposed by Daniel Koshland, this suggests the "Hand in Glove" analogy. The ligand binds to a ground-state conformation, and the interaction energy drives the protein into a new, bioactive conformation. Modeling this computationally is difficult because it implies the protein's shape change is dependent on the specific ligand, requiring expensive "Induced Fit Docking" (IFD) protocols that refine side-chains after the ligand is placed.

2.1.2 The Conformational Selection Model

Ensemble docking is theoretically grounded in Conformational Selection. This posits that the protein naturally samples a variety of conformations in solution, even without a ligand. The "bioactive" conformation is simply one of these pre existing high-energy states (a "snapshot") within the equilibrium ensemble. The ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes this specific conformation. If the protein visits the open state naturally, we can capture it using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

2.2 Scales of Flexibility

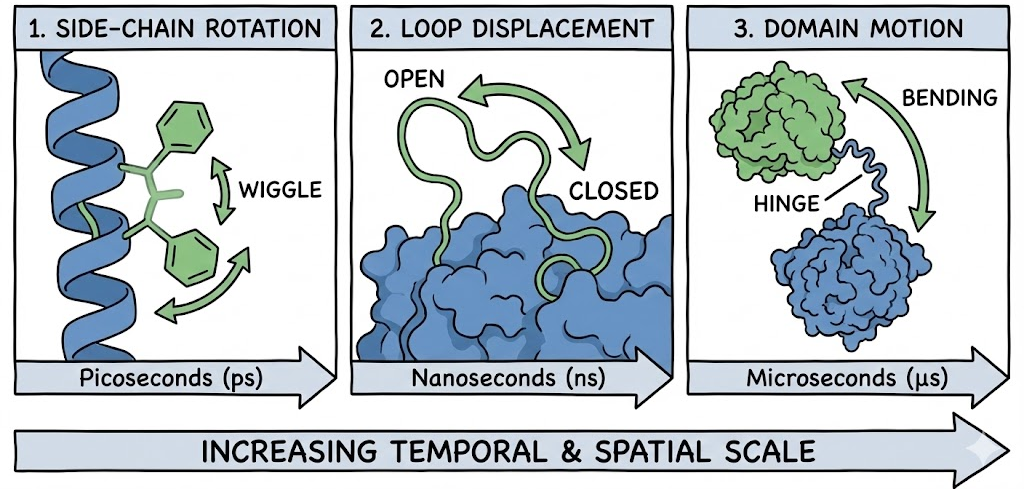

Protein motions occur across vast temporal and spatial scales. Static docking fails catastrophically with Loop and Domain motions, which ensemble docking is designed to capture.

- Side-Chain Rotation: Rotation of amino acid side chains (picoseconds).

- Loop Displacement: Movement of flexible surface loops (nanoseconds).

- Domain Motion: Hinge bending between protein domains (microseconds).

2.3 The "Unhappy Valley" of Scoring

Scoring failures often peak when the RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) between the docked pose and the native structure is between 1.5 and 2.0 Å. This "unhappy valley" represents poses that are geometrically close to the correct answer but are penalized by the scoring function due to minor clashes that a flexible receptor would easily accommodate. By ignoring these "wiggles," static docking ignores the entropic component of binding.

3. The Methodology of Ensemble Docking

Ensemble docking is a practical compromise between the extreme cost of fully flexible docking and the inaccuracy of rigid docking. Instead of making the protein flexible during the docking, we make the protein flexible before the docking by generating a discrete set of representative conformations.

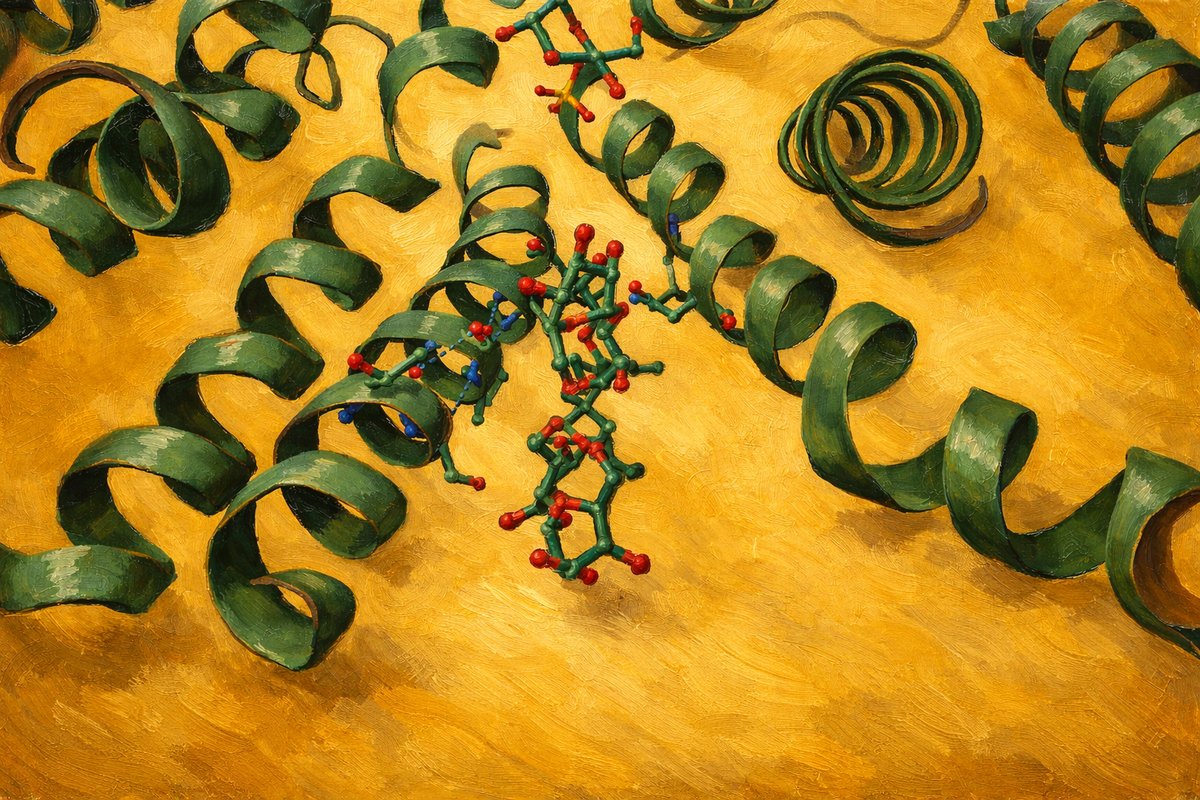

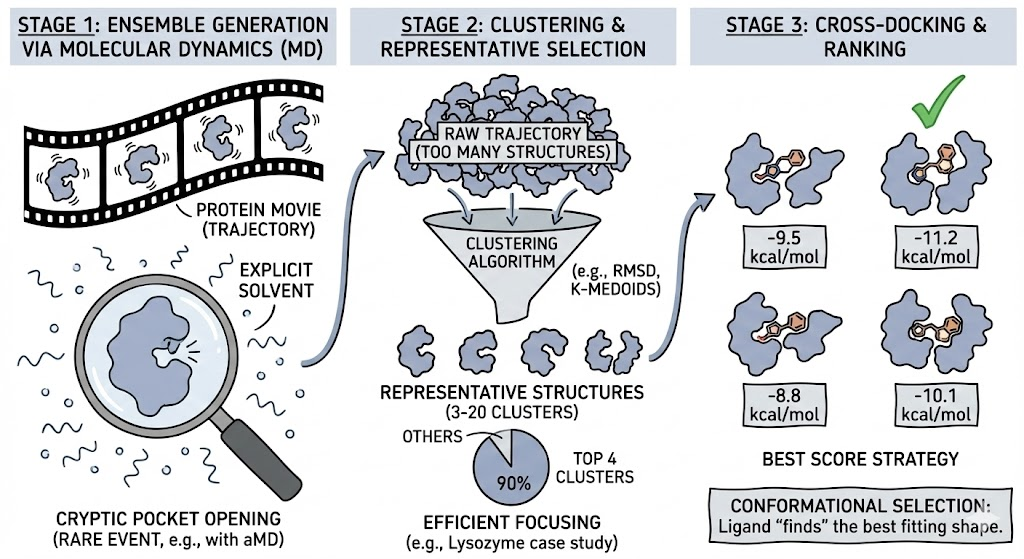

Stage 1: Ensemble Generation via Molecular Dynamics

While NMR ensembles or multiple crystal structures can be used, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are the gold standard for exploring the conformational space. MD simulations generate a "trajectory" a high frame rate movie of the protein wiggling in explicit solvent. This captures the crucial role of solvent in stabilizing transient conformations. For rare events, such as the opening of cryptic pockets, techniques like Accelerated MD (aMD) or Metadynamics are used to force the protein to explore high-energy states.

Stage 2: Clustering and Representative Selection

A raw trajectory contains too much redundancy; docking to 6,000 structures is computationally prohibitive. Clustering Algorithms reduce the ensemble to a manageable number of representative structures (typically 3 to 20).

- RMSD Clustering: Groups structures based on backbone deviation.

- K-Medoids: Selects the most "central" actual snapshot from the trajectory, avoiding artificial average structures.

In a Lysozyme case study, a 100 ns simulation yielded 15 clusters, but the top 4 clusters accounted for 90% of the population, allowing researchers to focus their docking efforts efficiently.

Stage 3: Cross-Docking and Ranking

The ligand is docked into each representative structure independently. The final ranking often uses the "Best Score Strategy," taking the single best score across all conformers. This mimics Conformational Selection: the ligand "finds" the best fitting shape.

4. Molecular Dynamics: The Engine of Flexibility

The validity of ensemble docking rests on the quality of the MD simulation. If the simulation does not sample the relevant "open" state, the docking will fail.

4.1 MD Post-Processing: "Dynamic Docking" Validation

MD is not just for pre-docking generation; it is also used post-docking to refine poses. This "dynamic docking" validation involves running a short simulation (e.g., 5-100 ns) on the static docking pose.

- The Logic: If a ligand is a true binder, it should be stable. If it is a decoy, it will drift away or exhibit high RMSD fluctuations.

- Results: This method has been shown to improve ROC AUC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) scores by over 22% compared to docking scores alone, effectively filtering out unstable false positives.

5. Case Study I: Lysozyme and Flavokawain B

To illustrate the power of ensemble docking, we examine the interaction between Lysozyme (LYZ) and the ligand Flavokawain B (FB).

Static docking of FB to the crystal structure of lysozyme yields mediocre binding energies. Researchers performed a 100 ns MD simulation of Lysozyme in water, clustered the trajectory, and docked FB to the top 4 representative structures.

Results:

- Cluster 1 (Dominant state): -28.41 kJ/mol.

- Cluster 2 (14% of population): -29.37 kJ/mol (Best Binder).

The ensemble approach identified Cluster 2, a conformation representing only a minority of the simulation time as the optimal binding state. This conformation allowed for specific interactions with residues Glu-35, Trp-108, and Arg-114 that were not accessible in the dominant crystal like conformation.

6. Case Study II: Hunting Ghosts: Cryptic Pockets in IL-2

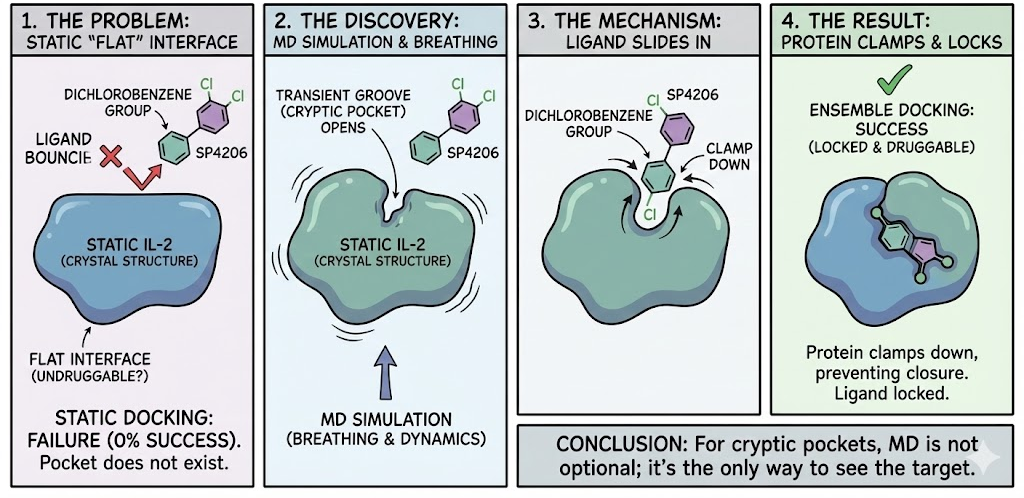

The most dramatic application of ensemble docking is the discovery of Cryptic Binding Sites pockets that do not exist in the ligand-free crystal structure but open transiently due to protein dynamics.

6.1 The Interleukin-2 (IL-2) Problem

IL-2 is a critical cytokine with a "flat" interface considered undruggable. Researchers at D. E. Shaw Research used unbiased, long-timescale MD simulations to study the binding of inhibitor SP4206.

6.2 The Solution

The simulations revealed that the "flat" surface of IL-2 breathes. A groove opens transiently even without the ligand. When SP4206 is present, its hydrophobic dichlorobenzene group slides into this transient groove, preventing it from closing. The protein then clamps down, locking the ligand in place.

A static docking attempt on the apo IL-2 structure would have failed 100% of the time because the pocket simply did not exist in the input coordinates. This demonstrates that for cryptic pockets, ensemble docking is the only viable approach.

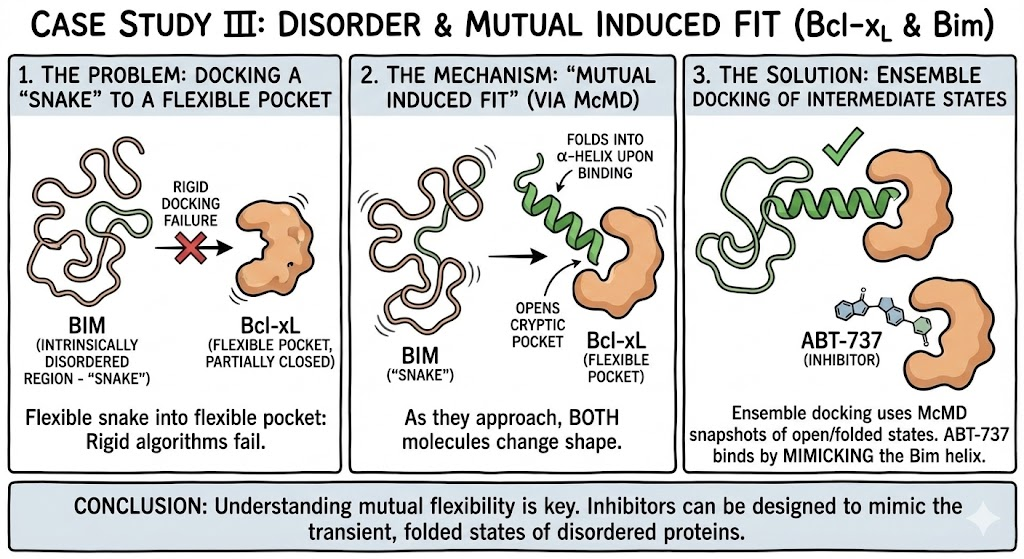

7. Case Study III: Disorder and Mutual Induced Fit (Bcl-xL)

Bcl-xL, a cancer drug target, binds to the Bim protein, which contains an Intrinsically Disordered Region (IDR). Docking a flexible snake (Bim) into a flexible pocket (Bcl-xL) is the ultimate nightmare for rigid algorithms.

Simulations using McMD (Multicanonical MD) revealed a mechanism of "Mutual Induced Fit". As they approach, both molecules change shape: Bcl-xL opens a cryptic pocket, and Bim folds into an α-helix upon binding. Ensemble docking using snapshots from the McMD trajectory successfully identified the intermediate "open" states, explaining why inhibitors like ABT-737 bind with high affinity by mimicking the hydrophobic residues of the Bim helix.

8.The LiteFold Solution: A Unified Infrastructure for Ensemble Docking

The transition from static to ensemble docking has historically been hindered by high technical barriers. Traditional workflows are often fragmented, requiring researchers to juggle disparate command-line tools for simulation, clustering, and docking, all while managing heavy computational resources. LiteFold addresses these challenges by providing a unified, cloud-native infrastructure specifically designed to streamline the complexities of dynamic drug discovery.

8.1 Removing Infrastructure Friction

Conducting ensemble docking typically requires access to High-Performance Computing (HPC) clusters to run computationally intensive MD simulations. LiteFold abstracts this complexity entirely. By offering a browser-based "Physics Engine Infrastructure," it allows researchers to launch simulations ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds without configuring complex environments or managing GPUs. This democratization of compute power ensures that the "wiggling" of proteins is accessible to all researchers, not just those with dedicated supercomputing access.

8.2 Seamless Integration of Dynamics and Docking

A critical bottleneck in ensemble docking is the handover between the MD simulation and the docking protocol. Traditionally, this involves manual extraction of frames, file conversion, and scripting to batch-process docking jobs. LiteFold integrates these steps into a cohesive pipeline.

- Automated Ensemble Generation: Users can run MD simulations via the Dynamo module directly in the browser. The platform enables the inspection of trajectories and the selection of representative conformations without the need to download gigabytes of trajectory files.

- Unified Workflow: Once representative structures (snapshots) are identified, they can be immediately utilized in the docking workflow. This integration reduces the "feedback latency" between observing a protein's motion and testing its druggability.

8.3 Advanced Analysis Capabilities

LiteFold moves beyond simple pose generation by incorporating analysis tools that are essential for evaluating ensemble results. The platform’s infrastructure supports the handling of large-scale experimental datasets and annotations, ensuring that the ensembles generated are biologically relevant. By centralizing the storage and analysis of simulations, LiteFold allows for a more rigorous assessment of ligand stability and binding thermodynamics, directly addressing the "Unhappy Valley" of scoring where static methods fail.

9. Bridging the Gap: From Static AI Predictions to Dynamic Ensembles

While AI-driven structure prediction has revolutionized structural biology, it often yields static snapshots that bias towards the most stable state, frequently missing the high-energy "open" conformations required for ligand binding. LiteFold serves as the bridge between these static AI predictions and the dynamic reality required for successful drug design.

9.1 Breathing Life into Static Models

AI models excels at predicting the ground-state structure of proteins from sequence. However, these models often fail to capture cryptic pockets or transient conformational changes. LiteFold leverages these static predictions as a starting point, using its integrated physics engine to "breath life" into the structures. By running MD simulations on AI-predicted models, LiteFold generates a conformational ensemble that explores metastable states, such as the DFG-out conformation in kinases, which are often missed by static prediction alone.

9.2 Interactive Feedback Loops

One of the most powerful features of LiteFold is the reduction of feedback loops in the design process. In a traditional workflow, modifying a ligand to fit a new protein conformation might take days of set-up and calculation. LiteFold’s DeNovo and interactive design modules allow researchers to edit molecules and immediately observe changes in predicted binding metrics against the generated ensemble.

- Real-Time Optimization: Researchers can use fragment growing or the molecule editor to refine compounds within the context of the dynamic pocket.

- Dynamic Validation: As new molecules are designed, their binding affinity is recomputed against the ensemble, providing instant insight into how chemical modifications influence binding to flexible targets.

9.3 The Convergence of AI and Physics

LiteFold represents a convergence of generative AI and physics-based simulation. It uses neural networks to predict initial structures and pockets, and then applies rigorous physics (MD) to validate and explore the conformational landscape. This hybrid approach ensures that drug discovery is not limited by the static nature of initial predictions but is enhanced by the rigorous thermodynamic sampling provided by the platform's infrastructure.

10. Conclusion: The Democratization of Flexibility

The "Lock and Key" model, while a foundational concept in biochemistry, has historically constrained drug discovery by promoting a static view of molecular interactions. We now understand that proteins are dynamic entities that dance, shift, and reshape themselves in response to their environment and binding partners. Rigid docking is akin to examining a single frame of a complex film; it captures a moment but misses the narrative.

Ensemble docking provides the necessary context, capturing the protein in its various states of motion. However, the complexity of generating and managing these ensembles has often restricted this powerful technique to computational specialists with access to massive infrastructure.

LiteFold fundamentally changes this landscape. By creating an integrated, cloud-native workspace that seamlessly combines Molecular Dynamics with docking and design, LiteFold democratizes access to protein flexibility. It removes the barriers of hardware configuration and fragmented software, allowing researchers to focus purely on the science. Whether identifying cryptic pockets in "undruggable" targets or refining lead compounds against a shifting active site, LiteFold provides the unified infrastructure necessary to navigate the chaotic, wiggly reality of the molecular world. The future of drug discovery is dynamic, and with platforms like LiteFold, that future is now accessible.

References

Amaro, R. E., Baudry, J., Chodera, J., Demir, Ö., McCammon, J. A., Miao, Y., & Smith, J. C. (2018). Ensemble Docking in Drug Discovery. Biophysical Journal, 114(10), 2271–2278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2018.02.038

cnapolitan2. (2021, September 27). Docking and scoring - Schrödinger. Schrödinger. https://www.schrodinger.com/life-science/learn/white-papers/docking-and-scoring/

Damilola. (2023, February 16). The Docking Method Showdown: Rigid Receptor Docking vs. Induced Fit Docking vs. QPLD. Medium. https://medium.com/@dbodun56/the-docking-method-showdown-rigid-receptor-docking-vs-induced-fit-docking-vs-qpld-8251d8927c7f

Gathiaka, S., Liu, S., Chiu, M., Yang, H., Stuckey, J. A., Kang, Y. N., Delproposto, J., Kubish, G., Dunbar, J. B., Carlson, H. A., Burley, S. K., Walters, W. P., Amaro, R. E., Feher, V. A., & Gilson, M. K. (2016). D3R grand challenge 2015: Evaluation of protein–ligand pose and affinity predictions. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design, 30(9), 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10822-016-9946-8

Lexa, K. W., & Carlson, H. A. (2012). Protein flexibility in docking and surface mapping. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics, 45(3), 301–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033583512000066

Ricci-Lopez, J., Aguila, S. A., Gilson, M. K., & Brizuela, C. A. (2021). Improving Structure-Based Virtual Screening with Ensemble Docking and Machine Learning. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, 61(11), 5362–5376. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00511

Tripathi, A., & Bankaitis, V. A. (2018). Molecular Docking: From Lock and Key to Combination Lock. Journal of Molecular Medicine and Clinical Applications, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.16966/2575-0305.106

We are on a mission to make molecular and structural biology related experiments easier than ever. Whether you are doing research on protein design, drug design or want to run and organize your experiments, LiteFold helps to manage that with ease. Try out, it's free.